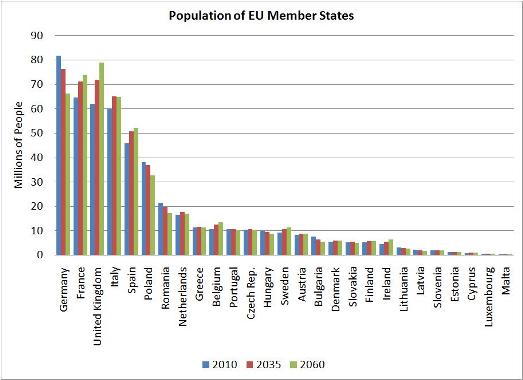

Source of graph: Eurostat

By John Richardson

AS delegates gather for this year’s European Petrochemical Association (EPCA) meeting in Berlin, which takes place on 5-9 October, it might be tempting to believe that Europe has turned the corner.

Supporting this argument has been the release of lots of positive economy data recently. For example, yesterday it was reported that eurozone retail sales rose by 0.7% in August – more than had been expected. And in September, economic output rose at its fastest pace since the summer of 2011.

But the long term challenges remain huge, as the blog discussed yesterday.

A good measure of the lingering impact of the economic crisis is that in the first half of this year, European ethylene production was 16% below its level during the same period in 2007. Propylene was 9% lower and butadiene 11% lower.

But Germany – which is, of course, the world’s fourth biggest economy and the biggest economy in Europe – remains a star performer within the region.

And the country’s chemicals industry seems to be doing fine. Although the German chemicals industries association, VCI, forecasts a 1% fall in the country’s chemicals industry turnover in H1 2013, it expects a 1% increase for the year as a whole to Euros188.7m.

Thus there is talk of 2014 being a better year than this year, with Germany helping to lead the whole of the euro area into a sustained, if slow, recovery.

The trouble is that while the short term direction might be up, Germany serves as a very worrying example of the long-term demographic challenge that faces the rest of the EU.

It has also its own set of problems that need addressing. These include:

- The slowdown in economic growth in China over the next decade. Germany has benefited from a boom in demand from China for capital goods and machinery that is now running out of steam.

- A continued failure to invest in ageing infrastructure and education, said the UK’s Daily Telegraph in this article. Germany’s top-rated university is Munich Technical, ranked 53rd in the word. The long-term opportunities in China could be nothing short of fantastic. “Less is more” will be the priority as China cuts back on the growth in manufacturing capacity for the sake of growth in manufacturing capacity. The focus has instead switched to higher-value manufacturing, energy efficiency and tackling the country’s chronic air, land and water pollution problems. Is Germany investing enough in the education and innovation essential to make the goods and services China will import in the future?

- “Germany’s industry federation, the BDI, has called for a drastic change in energy policy, warning that the €1 trillion dash for wind power, solar and other renewables is pushing power costs to levels that “endanger German competitiveness”, added the Daily Telegraph. “Electricity costs 30% more than in the rest of Europe, and twice as much as in the US. Natural gas costs four times more than in the US as the shale revolution alters the global economic landscape at lightning speed, leaving parts of Germany’s chemical and plastic industry under mortal threat,” the newspaper added.

- The OECD says Germany has one of Europe’s most rigid labour markets, despite the Hartz IV reforms a decade ago. It is still very hard to lay off workers, creating a barrier to technology start-up companies.

- Productivity per worker grew by just 0.6% a year from 2000 to 2010, compared with 1.4% for other rich countries.

- Germany ranks 106th for starting a firm in the World Bank’s ease of doing business index. It ranks 31 for mobile broadband, 75 for soundness of banks, 127 for hiring and firing, and 139 for wage flexibility, according to the World Economic Forum index.

- While nobody can dispute that Germany hugely improved its competitiveness during the early years of the euro, people are now asking, because growth has weakened, whether this was mainly achieved by suppressing wages. “Real disposable income per capita in Germany has been growing at half the rate in France since the launch of the euro. They have been ripping off their own people to build up pointless trade surpluses,” Charles Dumas from Lombard Street Research told the Daily Telegraph. “Their weakness is a reliance on foreign demand, which is no longer forthcoming from emerging markets. They were bailed out for a while by China’s excess investment, but China wants to stop doing the wrong thing,” he said.

The often-touted solution to this latter problem is that Germany needs to focus on boosting domestic consumption in order to rebalance its growth away from exports. But because of its demographic time bomb – for example the European Commission expects the country’s workforce to shrink by 200,000 a year this decade – where is all this extra consumption going to come from?

What can chemicals companies do to help Germany in its transition to a new growth model? This would be a fascinating topic for discussion at this year’s EPCA meeting.