By John Richardson

Last week, the blog gave a presentation at the ICIS Asian Polyolefins Conference in Jakarta during which we highlighted the anxiety over the impact of increased low cost ethylene and derivatives exports from the US.

But only 3.9 million tonnes of ethylene and derivatives are forecast by ICIS Consulting to be surplus to domestic needs in 2020 compared with 3.4 million tonnes in 2010 and 1.6 million tonnes in 2015.

Compare this with the Middle East where ethylene and derivatives surpluses are expected to rise from 14.3 million tonnes in 2010 to 22 million tonnes in 2015 and 26 million tonnes in 2020.

“So, why all the fuss about the US?” one the delegates, quite rightly, asked.

The reason is this: The subtext, we think, of the many discussions the blog has had with people in the polyolefins industry during 2013 about US capacity additions is anxiety over demand.

Few people we have spoken to have any great confidence that we are in sustained economic recovery. They see years of volatile, uncertain and often weak growth ahead, making it harder to justify investments, which, in volume terms, seem relatively small.

Here is our explanation about why we think this is the case and how, in incredibly broad terms, the problems can be fixed (the details we all need to work on. This is going to be really difficult, but we need to start now):

- Europe faces an extended period of deflation as demographics erode total demand for everything made from chemicals and polymers. It is nothing short of a tragedy that a generation of young people in southern Europe in particular face a bleak future of high unemployment with all the loss off self-esteem and hope, as well as economic insecurity, which this entails.

- As for the US, nothing is working at the moment, especially quantitative easing (QE), as this damning Wall Street Journal article by former US Fed official Andrew Huszar further underlines.

- Politicians and companies in the West need to recognise that demographics drive demand and use this as the basis to build a recovery plan, involving investments in education and innovation in order to make the products and services of the future.

- Asia has experienced a “sugar high” from QE, which, sooner or later, will have to be withdrawn.

- We will then be left with what will drive the bulk of demand over the long term. What will drive most of demand in Asia will not be soaring property prices and a small, rich elite getting even richer, whilst a much-poorer middle class also spends beyond its means and so gets into deep debt as it tries to “keep with the Joneses”.

- Instead, it will be mainly about enabling hundreds of millions of more people to emerge from poverty, thus allowing them to afford low-cost modern-day consumer goods for the first time. This, again, requires investment in education – and also in sanitation, fresh water supplies, food transportation and preservation and infrastructure.

- The other “sugar high” that has already come to an end is the commodity Supercycle, which has been driven by China. As China reduces investment, demand growth for commodities – from iron ore to chemicals and polymers – will slow. If China gets it right, the potential offered by greater domestic consumption is enormous. But the transformation process could take many years.

Conference delegates focused heavily on the need for infrastructure investment in countries such as Indonesia and Thailand and how governments are responding. For example, 83% of government expenditure in Thailand is at the moment focused on improving the country’s ports, roads and rail links etc, said Petch Niyomsen, Manager, Strategy and Planning Department, at Siam Cement Group Polyolefins.

This is great news in the respect that it could help with poverty alleviation.

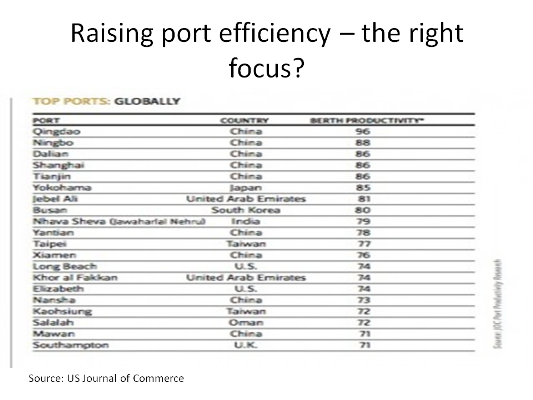

But we worry that infrastructure investments might be too heavily focused on a mistaken attempt to grow manufacturing sectors – for instance, by increasing the speed of cargo handling at ports in Asia, which other than in China, lags way behind that of the West (see the the table at the beginning of this post).

These investments might be based on the mistaken assumption that demand drivers haven’t fundamentally changed and that politicians in the West and elsewhere are successfully nudging the world back to where we were in 1983-2007 – the economic Supercycle. But you cannot turn 55-year-olds back into 30-year-olds.

And we also worry that as ports, roads and power supply are improved across Asia (the latter two types of investment can, however, be a great plus in getting rid of poverty), excessive amounts of manufacturing capacity will be added. We are seeing evidence if this in the polyester chain, despite already substantial oversupply.

Refinery, cracker and derivatives capacities might also be added in Asia in order to support growth in an excessive expansion of downstream manufacturing.

The end result might well be a rise in trade protectionism as markets become much more regional.

Globalisation has already started to slow down, as Daniël de Blocq van Scheltinga, manager and founder of the Hong Kong-based financial advisory company Polarwide, told the conference.

“Global capital flows peaked $11 trillion in 2007 and amounted to only one-third of that last year,” he said.

“Since the financial crisis in 2007, big emerging markets, such as those that make up the BRICs, have imposed more state intervention, hindering the flow of money and goods,” he added.

“Trade has become more regionalised as countries gravitate towards like-minded neighbours [we will look at this theme in detail in a blog post next week when we examine the rise of regional trading blocs].

“Big emerging markets have become more regionalised to protect and develop specific industries after obtaining skills and technology from foreign countries.”

Here is the sting in the tail: We think that as the world struggles to absorb excess petrochemical and downstream manufacturing volumes, we are going to see more antidumping, safeguard and other trade protectionist measures.

This might challenge the conventional wisdom that says that the US has an unbeatable advantage in terms of the variable cost per tonne of ethylene production. The advantage will become academic if trade measures prevent the US from exporting its surpluses.

We remain convinced that we are not pessimistic, just realistic.

And so we think it is realistic that chemicals companies should prepare for a more fragmented and more regional trading environment –unless or until a new economic growth model is firmly in place.