By John Richardson

ACHIEVING approval for any new petrochemicals projects in China is going to be a lot harder in the future, is a a growing view across the chemicals industry.

A senior executive with a US-based polyolefins producer, for example, told the blog recently: “It looks as if Chinese chemicals companies are finding it harder to get hold of capital, whilst they are also being forced to look harder at cost curves.”

“There is also the environmental factor, which is why we take a very conservative view of production from all the announced coal-to-olefins (CTO) and methanol-to-olefins (MTO) projects in China.” [CTO starts with coal as the first raw material, whereas MTO is based on imported methanol].

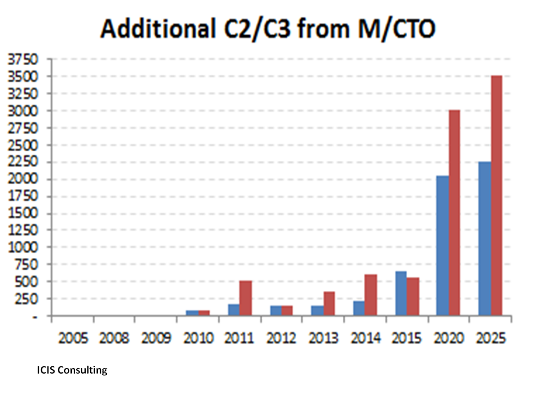

And, certainly in the short term, we agree with this conservative view when it comes to CTO and MTO production, as the above chart illustrates. We remain to be convinced that new supply from these production routes will come anywhere close to overwhelming the market, given doubts over margins and the ability to operate these plants and consistently stable rates.

But as for the wider and longer-term outlook for new projects, taking into account, of course, the fact that most new olefins capacity is in China likely to be based on the incredibly well-establishing naphtha-cracking route, we are not so sure.

The reason is that jobs might still be more important in some cases than capital costs, environmental protection and cost curves because of the collapse in exports as a component of GDP growth.

Employment creation is receiving little additional benefit from exports because, as the China Daily wrote in this article: “Exports in 2012 made a negative contribution to GDP growth, and if you deduct speculative funds disguised as trade payments, you’ll find that exports were a drag on growth again in 2013.”

Why? A major reason, we think, is that the ageing of the Babyboomers will constantly weaken Western demand for things made in China.

Plus, higher labour costs are making it harder for some coastal manufacturers to compete.

And whilst blue-collar labour markets in eastern and southern China are tight, the further west you move in China, the greater the emphasis still remains on the multiplier effect that a new industrial complex can have on growth. Build a chemicals plant in these inland provinces and you end up with substantial direct and indirect employment growth which helps to raise income levels.