By John Richardson

US VICE president Mike Pence made a barely reported speech on 4 October in which his big theory was that Bill Clinton, George W Bush and Barack Obama misread China. Mr Pence said that the nation they embraced as a partner was instead a competitor.

It is important that you read the text of the speech in full on the White House website. What is as important as the words is the tone.

The vice president’s speech underlines my concern that we could well be heading for a new Cold War.

The world most of us grew up with has changed

From the collapse of the Soviet Union until 1991 until very recently, global markets only headed in one direction. Tariffs and other trade barriers fell as petrochemicals and other markets became more and more open.

This was the result of a lack of competition between Superpowers. The end of the Soviet Union meant that there was only one Superpower which was of course the US.

The constant rise in globalisation was the bedrock upon which the petrochemicals industry built its investment strategy. Companies were able to build plants just about anywhere in the world because of the certainty that exports would flow unheeded from one country and region to the next.

Note the past tense in the paragraph above. And yet we still hear petrochemicals companies only talk about feedstock advantage, good logistics and booming emerging markets growth when justifying the announcement of new projects. New political risks are being overlooked.

One of the reasons for this is that many business managers only started work after 1991. They have as a result no experience of a world of high trade barriers. It is very hard to plan for something that you haven’t experienced.

The increase in trade barriers since President Trump came to power in January 2017 is also very often dismissed as only very temporary – a dangerously complacent approach. Exposing this complacency are the words of Mr Pence, when he says in his speech:

The Chinese Communist Party has used an arsenal of policies inconsistent with free and fair trade, including tariffs, quotas, currency manipulation, forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, and industrial subsidies that are handed out like candy to foreign investment.

Beijing has directed its bureaucrats and businesses to obtain American intellectual property –- the foundation of our economic leadership -– by any means necessary.

Worst of all, Chinese security agencies have masterminded the wholesale theft of American technology –- including cutting-edge military blueprints. And using that stolen technology, the Chinese Communist Party is turning ploughshares into swords on a massive scale.

China now spends as much on its military as the rest of Asia combined, and Beijing has prioritized capabilities to erode America’s military advantages on land, at sea, in the air, and in space. China wants nothing less than to push the United States of America from the Western Pacific and attempt to prevent us from coming to the aid of our allies. But they will fail.

China’s economic importance

Countries and regions will have to make choices. They will have to decide whether to support the US or China in this new geopolitical world order. The choice will be between the US defence security umbrella and China’s economic importance, argues Douglas Dillon, professor of government at the Harvard Kennedy School.

“When I came [to power] we were heading in a certain direction that was going to allow China to be bigger than us in a very short period of time. That’s not going to happen anymore,” said President Trump in August

But as Professor Dillon adds in his FT article, the battle the US is picking over economic influence (geopolitical influence is another issue) is happening too late. China’s economy is already by purchasing power parity bigger than that of the US, is a top trading partner of all major Asian countries and has been the undisputed growth engine of the world since 2008.

Countries such as India and regions such as Southeast Asia will have to make difficult choices between defence security and maximising their economic growth.

Professor Dillon argues Australia and Japan have already made it clear that they will not trade off access to China markets for US defence security. But nobody can be certain what the new geopolitical and economic global map will look like and it won’t be static. Countries are likely to constantly switch sides.

China’s strong economic position does, however, mean there is one thing we can be sure of and it is this: Without access to the China market no world-scale petrochemicals project outside China can be economically justified.

This means that location, location and location are the most important three factors for deciding the viability of a new petchems investment. There is no point in having feedstock advantage if you are in a country or region that has aligned itself with the US and so, perhaps, cannot export to China at all.

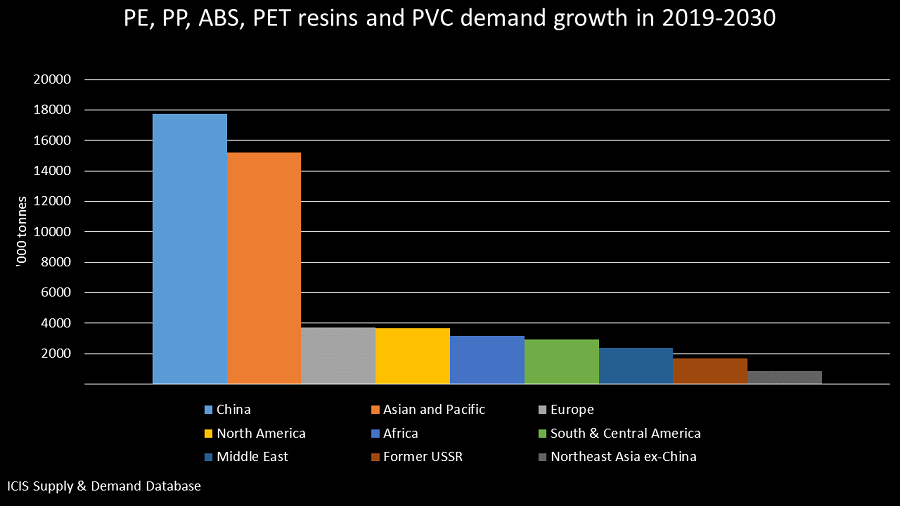

The above chart proves the point. It is another way of representing data you will have seen before on the blog. It shows that between 2019 and 2030, China will account for 17.8m tonnes of global demand growth in PE, PP, ABS, PET resins and PVC – 35% of the global total.

I make no apologies about repeating the message because I am still hearing people talk about booming emerging markets growth. In statistical reality, though, the only real boom with global significance for petrochemicals has been in China and will remain in China.