By John Richardson

CASH margins for Asian linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) for naphtha-based producers have turned negative for the first time since Q1 2015, according to an industry contact.

And this is of course before the flood of new US LLDPE production arrives in Asia. No matter how you crunch the numbers, the likely increase in US exports to 3.6m tonnes in 2019 from 2.2m tonnes in 2017 will have major negative consequences for global markets.

The disruption will be even greater if the US cannot export to China because of the trade war. Naphtha-based PE producers in smaller net imports regions such as Europe and Southeast Asia (SEA) would be under tremendous pressure.

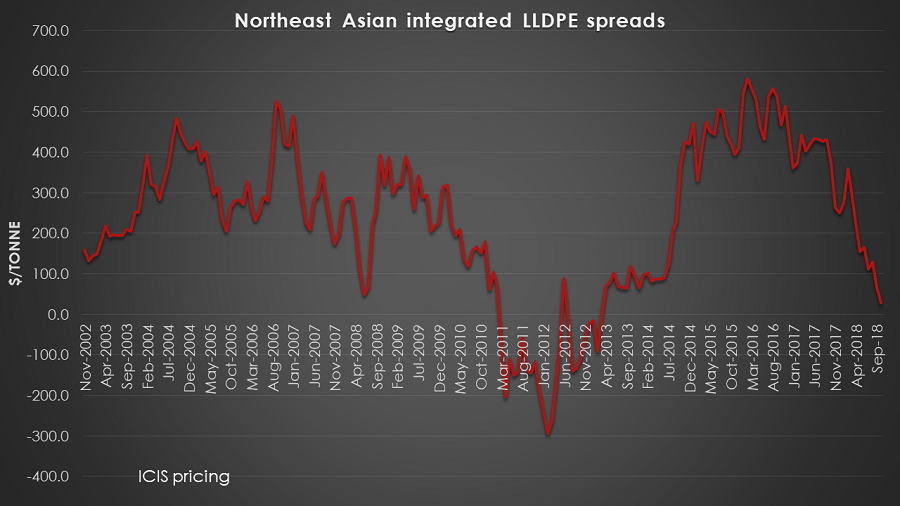

The above chart seems to confirm what my industry contact is saying. This shows Northeast Asian (NEA) LLDPE spreads including an extremely rough and ready estimate of co-product credits from benzene, toluene mixed xylenes, butadiene and fuel-oil type products etc.

I added together CFR China LLDPE C4 film grade prices and co-products which I assumed at 1.8 times the prices of naphtha per tonne. I then subtracted feedstock costs of making each tonne of ethylene – 3.3 times naphtha prices. Around one tonne of ethylene makes a tonne of LLDPE.

On this basis LLDPE spreads fell to just $28/tonne during the first week of October. This was the result of naphtha costs per tonne rising to more than $700/tonne and China CFR LLDPE prices remaining flat over their September average

The October spread was down from a September full-month average of $66/tonne – and both the October and September spreads were the lowest since February 2013 when spreads were slightly negative.

Spreads are obviously not margins as they don’t take into account production costs. But spreads at just $28/tonne so far October indicates, as I already said above, indicate that my industry contact must be right that cash margins are negative. Cash margins are anything above raw material costs minus co-product credits, salaries, interest costs, maintenance and repair costs and taxes and insurance.

Why this has happened

The weakness in LLDPE and is reflected in other grades of PE and polypropylene (PP) as my estimate of spreads across a range of grades is also sharply down.

Taking into account spreads for LLDPE C4 film grade, high-density PE injection grade, low-density PE film grade and PP raffia grade, spreads in the first week of October were again at their lowest level since February 2013.

What is happening given that, as I said, the big flood of new US LLDPE and also HDPE production has yet to arrive in Asia?

The run-up in crude and so naphtha prices is obviously a major factor behind the fall in margins.

For the broader economy this is also bad news. Countries heavily dependent on oil and gas imports are struggling with the inflationary impact.

Emerging market economies, whether or not they are major hydrocarbon importers, have been hurt during most of this year by the strength of the US dollar. The greenback has risen in value because of the apparent strength of the US economy and higher US Federal Reserve interest rates.

This has been reflected in consistently negative sentiment in SEA polyolefins markets.

But whilst India is a major oil and gas importer, and the rupee keeps falling to record lows against the US dollar, its polyolefins demand growth remains very strong.

This is a result of further catch-up growth on the rise in income levels and a big push to improve crop yields through the use of HDPE water pipes and LLDPE and LDPE agricultural film.

And in China, 2018 PE demand growth looks set to be stronger than we expected by some 450,000 tonnes because of the continued boom packaging demand for internet sales. This is despite the negative impact of the trade war.

I shall deal in detail with the strength in Indian and Chinese PE markets in later post.

For anyone selling PE and China the retreat to negative NEA LLDPE margins might therefore not feel logical. The strength in individual markets should not, however, result in you ignoring the broader risks.

What lies ahead

One broader risk is what oil-price driven inflation will do to US consumer demand. More expensive crude has already wiped out the gains from last year’s tax cuts.

There is also the risk from higher interest rates. President Trump is blaming an “out of control Fed” for raising interest rates too aggressively and too quickly. This seems to be in response to this week’s retreat in stock markets which, if sustained, may jeopardise Republican chances in November’s mid-term elections.

Even if the Fed were to ease back on its plan to raise borrowing costs on another four occasions over the next 12 months, this would only make the problem worse. The problem is the vast build-up of debts since 2008 which at some point will have to be paid back or written off.

Cheap money for longer would encourage more debts that are not justified by the long-term fundamentals of demand in the US. The Fed’s economic stimulus since 2008 has brought forward demand from a diminishing pool of demand because of the ageing US population.

We could thus be close to the moment when we finally have to reckon with this debt, as a result of the combination of oil price-driven inflation and higher borrowing costs.

If not now it will happen soon with the insolvency of the US government just around the corner. The Congressional Budget office has warned that the US will face decisions on whether to default on the Highway Trust Fund (2020), the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund (2025), Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund (2026) and then Social Security itself (2031).

If the US decides to bail these government services out it will either have to make cuts elsewhere or raise taxes or default on the debt itself.

What happens in the US economy has broad global implications, as does what happens in the Chinese economy.

This returns us to the trade war, which, along with higher interest rates, explains why global stock markets are heading for their worst week in six months. The trade war will get worse, in my view, as we very possibly end up in a new Cold War. This will have major negative economic consequences for the Chinese and other economies.

It is interesting that whilst Chinese PP demand growth in 2018 looks set to surprise on the upside, PP demand growth seems likely to be disappointing. The Chinese PP market will again be the subject of a future post.

Why PP is set to disappoint is because it is less used in packaging than PE –so no big benefit from booming internet sales. A lot of PP also goes into durable applications that are being badly affected by US tariffs on Chinese imports of plastic products.

The upshot of all the above for polyolefins producers in general is that they should build a scenario where markets get worse on expensive crude and higher interest costs equalling weaker demand.

And for the petrochemicals industry in general companies should game-plan a global recession over the next few months. However unlikely you feel this is right now because of the strength of your sales so far this year, I advise that you consider a new recession as a scenario.