…..and that’s assuming there is no trade war with China!

By John Richardson

THE MORE you dig into the data the more it seems that the US might struggle to find a comfortable home for all of its new polyethylene (PE) production, even without a trade war with China.

Using linear low-density PE (LLDPE) as an example, US exports as a percentage of US production rose from 10% in 1993 to 46% in 2017 (1993 was the first year that the US exported any material).

These increases were perfectly manageable in a world of strong demand growth and surging import demand in countries such as China, and in regions such as Latin America and Asia & Pacific.

But the first seven months of this year seem to represent a watershed. US exports totalled around 1.9m tonnes in January-July – a 45% increase over the same period in 2017.

What is much more significant is what these exports were as a percentage of production – 56% based on our estimate of annual 2018 production of 5.7m tonnes (divide annual production by 12, multiply by seven and then calculate exports as a percentage of June-July production).

Now let’s forecast what could happen next year. In 2019, we are expecting US production will increase to 6.5m tonnes.

Let’s assume that exports are again at 56% of production in 2019.This seems reasonable given strong production growth over very low local consumption growth (production growth at 12% in 2019 over 2018 with domestic demand up by just 2%).

Top US export destinations cannot take the strain

The end-result would be exports of 3.6m tonnes – no less than 64% higher than full-year 2017 exports of 2.2m tonnes.

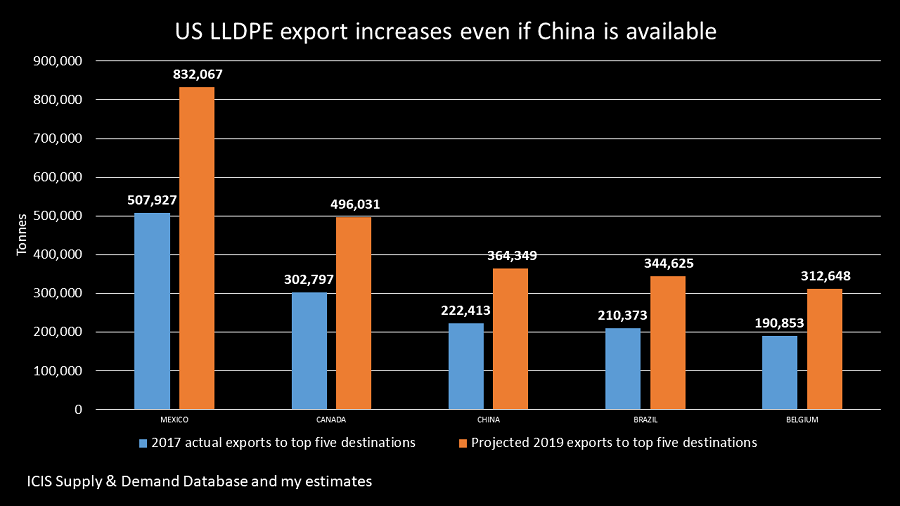

In 2017, the top five US export destinations were Mexico at 23% of total exports followed by Canada at 14%, China at 10% and Brazil and Belgium which were each at around 9%.

Let’s imagine that the US can export freely to China in 2019 because the trade war has come to an end.

See the chart at the beginning of this blog post for what could happen. The numbers should, quite literally, take your breath way as they would each represent a 68% increase over 2017.

Only China seems capable of being able to absorb such a big increase in US shipments. But even in China, such a significant rise in US cargoes would be bound to result in a pricing battle with Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian exporters.

As for all the other big US export destinations, the projected increase in 2019 US exports would be much more than our forecasts of their total import requirements.

Take Belgium as an example. We forecast its net imports (imports minus exports) at 208,000 tonnes in 2019 as against US imports of 318,000 tonnes.

Clearly this cannot happen. US LLDPE producers must be spreading their net wider to raise exports in other markets.

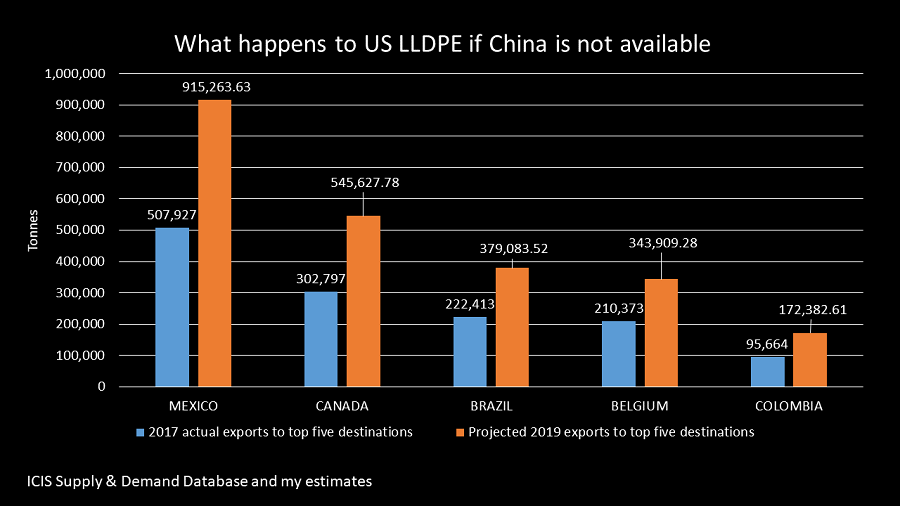

Now let’s assume that the US cannot export any LLDPE to China in 2019, production is again at 6.5m tonnes and exports at 56% of production.

The end-result is the table below, showing top five US export destinations in 2019 – this time minus China. I’ve again compared these with actual 2017 imports

This represents and even bigger threat to smaller markets where the US only has a very minor presence. Exports would on average to increase by 75% in 2019 to the top five US export destinations compared with actual imports in 2017.

A rise in LLDPE trade protectionism

Perhaps US exports as a percentage of production will be less than 56% in 2019 – maybe 2017’s 46%. This would result in exports totalling 2.9m tonnes in 2019, based again on 6.5m tonnes of LLDPE production.

But if you carry out the alternative mathematics, this would still require a rise in US exports to its major 2017 destinations to levels that are unsustainable – even assuming that the US is able to ship to China.

Exports at 46% of 2019 production would also imply local demand growth significantly growth stronger than we are forecasting. How can this happen in a market as mature as the US?

Or US production might be lower than our expected 6.5m tonnes in 2019. Output increases could be delayed to 2020 or beyond in order to give more time for global markets to balance out.

Another outcome is that US LLDPE exports force operating rate cutbacks elsewhere in the world. Older, higher cost naphtha-based LLDPE may shut down entirely.

But will producers elsewhere roll over and die? Or will they instead successfully petition for trade protection?

Because the US government has become so much more protectionist, it is hard to see why other governments will not follow suit.

High cost LLDPE plants are not standalone. Shut an LLDPE plant down and you threaten the survival of wider refinery-steam cracker complexes.

In doing this you would jeopardise local supplies of transportation fuels and the many, many downstream manufacturing jobs that are dependent on the rest of the output from steam crackers – benzene, butadiene and propylene derivatives etc.

This is a further reason to expect calls for protection against low cost US LLDPE imports. We could also see government financial incentives that keep higher cost LLDPE plants operating.

Demand threatened, even without a trade war

The other problem is demand. Let’s assume for the sake of optimism rather than realism that the US/China trade war is over by Christmas – ending its negative impact on global economic growth.

That would still leave the risk that further Fed interest rate rises will exert additional strain on emerging market economies.

Key US export destinations such as Brazil could suffer further currency weakness against the US dollar.

Our base case sees Brazilian LLDPE demand growth of 5% over 2018 to consumption of 11.5m tonnes in 2019. This has to be in doubt because of the contagion effect on Brazil of the weakness in emerging markets and economic problems specific to Brazil.

Other key emerging market destinations for US LLDPE could face similar economic pressures – for example, India, Vietnam and Indonesia where growth in LLDPE imports has been strong.

These three countries were very far down the 2017 league table of US LLDPE exports: India was just 1.2% of the total, Vietnam 0.3% Indonesia 0.2%.

These are the kind of countries where the US needs to win more sales if it is going to comfortably place its surpluses.

Will it be able to achieve this if the economic pressure that we have seen on emerging markets in 2018 is replicated next year, even without the negative global economic impact of a US/China trade war,? In my view, no.