By John Richardson

THE ground has shifted under our feet once again. Just as it seemed as if the US and China would complete a trade deal by the 2 March deadline, the prospects of an agreement have suddenly diminished.

This is the result of the Trump administration declining an offer from two Chinese vice-ministers to fly to Washington for preparatory talks. The talks were meant to pave the way for higher-level discussions at the end of January.

A problem is US insistence that any deal includes China stopping what the US claims is forced technology transfers by foreign venture partners to their Chinese partners. The US also wants China to abandon state subsidies for manufacturing.

Good luck with that. If China were to concede on this latter point it would run a major risk of economic stagnation. This makes such a concession quite simply impossible.

China has to maintain heavy funding of higher value industries such as electric vehicles, artificial intelligence and robotics if it is to stand any chance of escaping its middle-income trap.

The disastrous One Child Policy has pushed China into a middle-income trap some ten years too soon. China is at risk of becoming old before it is rich.

The mood music may of course change again as we live in very uncertain political teams. But if a deal is reached by the March deadline, it would only be paper thin as there is insufficient time to properly address the US and China’s major economic and geopolitical differences.

This would make any deal likely to fall apart, leading to a resumption of the trade war/Cold War. A key risk is how a deal would go down with President Trump’s core supporters.

Yesterday’s events also serve as a sober reminder of what is at stake for the US petrochemicals industry. US PE, ethylene glycols and styrene are subject to 25% Chinese import duties because of the trade war, with US styrene facing the added burden of Chinese antidumping duties.

China, as I shall detail below, is by far the biggest import market for all of these products. Assuming that the US cannot export to China because of the tariffs, the US petrochemicals industry would be in deep trouble.

US LLDPE exposure to China has just got worse

Of the three major grades of PE, US LLDPE is the most exposed because of a.) The scale of US capacity increases and b.) The size of China’s projected deficits in 2019 and beyond.

Last year was a great year for Chinese LLDPE for reasons I shall detail in a later post. This resulted in net imports totalling what I estimate will be 4.6m tonnes – 44% higher than in 2017!

This year is probably going to see negative or flat import growth on increased local production and a weaker Chinese economy.

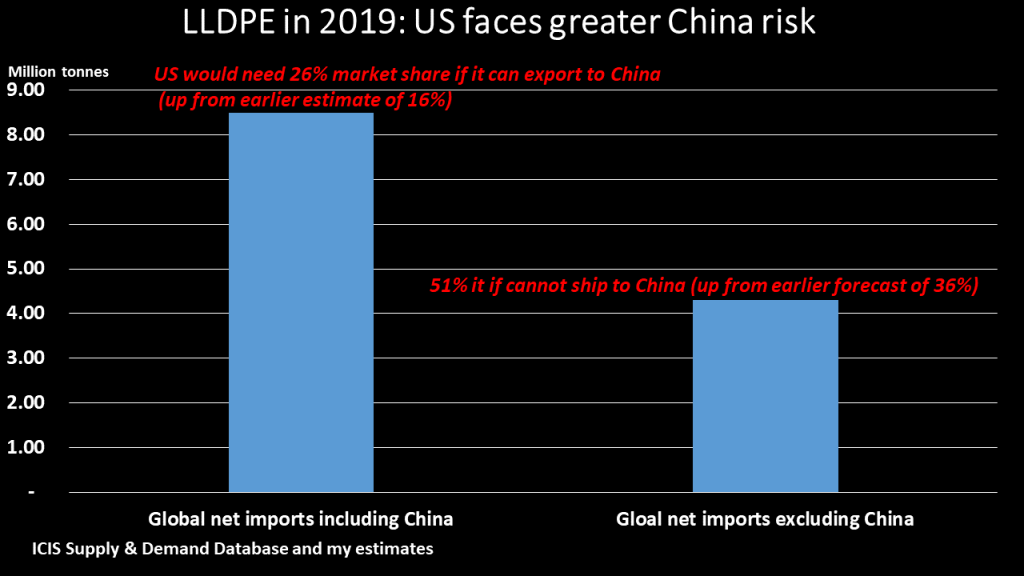

But even if we assume that net imports decline to say 4.2m tonnes – 10% lower than in 2018, this would still mean:

- The US would need a 26% share of the total global net import market if it can access China.

- A 51% share of the remaining global net import market if it cannot ship any cargoes at all to China.

These numbers take into account my guesstimate of import growth in other markets which I see as being weak in 2019.

I had earlier estimated that the US would need a 16% share of the total global net import market if it could ship to China in 2019 and a 36% share if it could not. These numbers were based on lower predictions for US net exports and Chinese net imports.

It looks equally grim in in ethylene glycols (EG). The US would need just a 9% share of the global net import market in 2018-2025 if it can move product to China. Excluding China and this increases to a completely unfeasible 53%.

Unlike in PE and EG, the US is not adding any styrene capacity. This the result of very weak global growth in the biggest styrene derivative, PS. US styrene exports have become more important to the US industry because of weakness in local downstream PS.

China will again remain by far the world’s largest styrene importer. The US would need a 37% share of the world’s net import market in 2018-2025 if it can export to China. This rises to 61% if China is unavailable.

The de-globalisation of petrochemicals

The US/China trade war is just one symptom of the rise of populist politics on growing public unrest over diminishing economic opportunities. Globalisation is going into reverse.

This should be a major topic of debate for the rich and famous who are taking part in this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, some of whom might be amongst the 26 richest people in the world.

The wealth of these 26 people last year reached a combined $1.4 trillion, according to Oxfam. This was the same amount as the total wealth of the 3.8 billion poorest people in the world, who account for 50% of the global population.