By John Richardson

LET’S START with the good news first. ICIS Data and Analytics had expected China’s demand for paraxylene (PX) to grow by in 2018 at 5.6% over 2017, but instead I estimate growth at 9.2%.

This was awesome news for the world’s major PX producers as the reason for the strong growth was higher than expected imports. Whereas local production looks likely to have been 10.3m tonnes in 2018, some 540,000 tonnes less than we had forecast, last year’s net imports soared to 15.9m tonnes when we had expected net imports at 13.9m tonnes.

The growth in China’s net PX imports over the last eight years has been nothing short of staggering. In 2010, they totalled just 182,566 tonnes.

Oil-to-refinery-to-PX producers such as BP and ExxonMobil could benefit further over the next few years if this trend continues. In a world where gasoline demand is set to decline on growing fuel efficiency, the rise of electric vehicles and the drop in the number of miles being driven as Western populations grow older, there is an opportunity to use spare catalytic reformer capacity to make more PX.

Catalytic reformers of course make mixed xylenes (MX) and toluene that can be used as octane boosters in gasoline. MX is the feedstock to make PX. MX produced directly by reformers is fed to PX plants. Toluene can also be converted into more MX to again supply PX facilities.

But how long will this opportunity last? I think that China will push towards PX self-sufficiency more quickly than many people think through major investments in new refinery-and-chemicals capacity. An aggressive drive to self-sufficiency would fit with China’s desire to control more of manufacturing value chains in general as it tries to add value to its economy. So I am afraid that my good news was highly qualified.

Now let’s focus just on the bad news from the perspective of overseas purified terephthalic acid (PTA) producers. China’s PTA production in 2018 looks as if it was no less than 2.4m tonnes more than we had anticipated.

Yes, this is not a typo – 2.4m tonnes. This would leave last year’s production at 39.2m tonnes, 12% higher than actual confirmed production in 2017. Instead of China being in what we had expected would be a net import position, China’s net exports totalled 58,014 tonnes.

As a reminder, PX is a raw material needed to make PTA. PTA is then used to make polyester fibres, films and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles.

Building factories for the sake of building factories

I must stress that these PX and PTA production numbers are preliminary numbers and maybe be wrong when we have completed our final revisions. But the PX trade data for 2018 is accurate. Quite clearly, therefore, the big increase in net PX imports versus what we had expected means that PTA production must have been surprisingly high.

Why did PTA plants run so hard in 2018 then? One reason seems to be improved spreads. In 2017, the spread between the costs of PX feedstock and PTA prices in China (it takes 0.67 tonnes of PX to make a tonne of PTA) averaged $83/tonne. But last year the spread rose to $140/tonne. This likely reflects stronger downstream demand as spreads between PTA and mono-ethylene glycol feedstock costs polyester fibre prices also edged up.

Polyester fibre demand seems to have benefited from the heavy restrictions on imports of recycled PET bottles, flakes and other scrap plastic that the Chinese government introduced from January last year for environmental reasons. Recycled PET can be used to make polyester fibres. Reduced availability of recycled PET could have boosted demand for virgin polyester fibre. Recycled PET imports fell to 1.8m tonnes in 2018 from 3.4m tonnes in 2017.

But there is another argument that explains why Chinese PTA plants ran harder than we had thought in 2018.

From 2009 onwards, China launched a major wave of investments in new PTA plants. This was during the 2009-2017 economic stimulus programme when China was responsible for 50% of the $33 trillion of total stimulus pumped into the global economy.

This wasn’t about building PTA and other manufacturing plants based on long term supply and demand analysis. The government had instead panicked because of the potential damage from the Global Financial Crisis.

Banks were ordered to lend money to companies with virtually no strings attached. The message essentially was, “Build factories for the economic multiplier sake of building factories, even at the risk of creating oversupply.” The effect on the global PTA industry was quite staggering. In 2010, China’s net PTA imports were 6.6m tonnes. Last year, as I have already said, China was in a net export position of 58,014 tonnes.

These investments might make sense in the long run. But the speed of local PTA capacity additions must be a problem.

It could be that in 2018 not all PTA producers were making good money because of the rapid growth in local competition. But they still ran hard because loans had been written by off by banks, which were asked to do so by local governments anxious to maintain employment as the economy slowed down.

This meant that some of China’s PTA plants might have operated as hard as possible as debt write-offs meant they only had to cover variable costs. Improved spreads indicate that variable costs were more easily covered in 2018 versus 2017.

And what if China’s economy continues to slow down in 2019 and beyond? China might return to exporting deflation to the rest of the world as Chinese PTA and other companies try to get rid of surplus capacity in overseas markets. Sure, this would create more trade tensions. But China might feel it has no choice but to raise exports because of weak domestic growth.

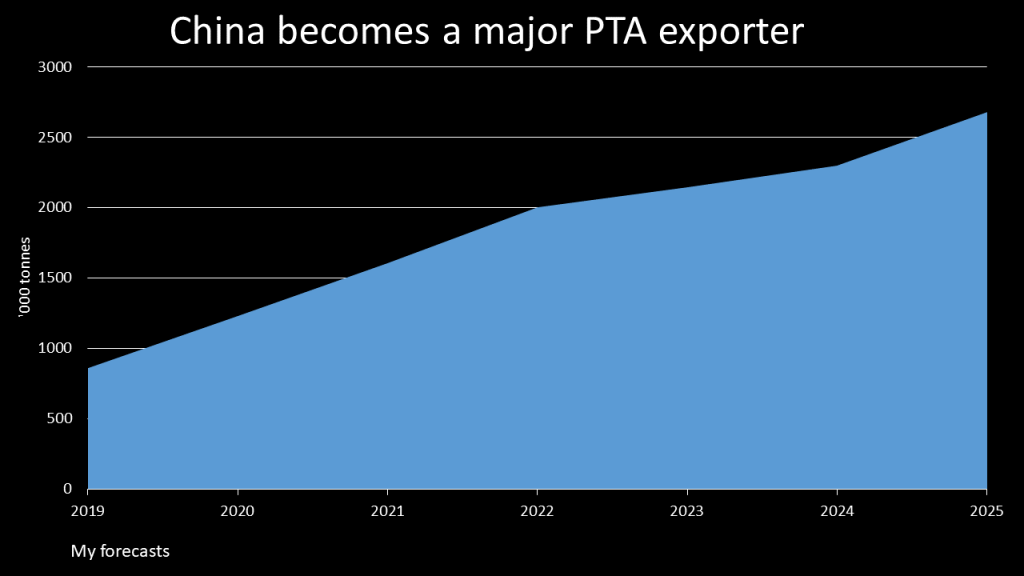

2.7m or even 3.3m tonnes of net PTA exports by 2025

We had expected China’s PTA plants to run at an average operating rate of 85% in 2018. But the preliminary production data indicate that they ran at 91%.

Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, and of course my guesstimates will be wrong, that capacity utilisation up until 2025 will be higher than our base case. Our base case assumes average rates of 80% in 2019-2025. This would result in China being in a net import position in up until 2022 before moving into modest net exports thereafter.

If you raise average rates to 84% in 2019-2020, China is in a net export position throughout the period and is exporting 2.7m tonnes of PTA in 2025. Might capacity utilisation be even higher? Raise rates by just another percentage point in 2025, from 92% to 93%, and net exports jump to 3.3m tonnes.

Just ten years ago all you had to do make money was put any chemical or polymer on a ship to China. Life is now much more complicated as events in the polyester value chain so clearly demonstrate. There is still great money to be made, but the chemicals business is nowhere near as straightforward as it used to be.