By John Richardson

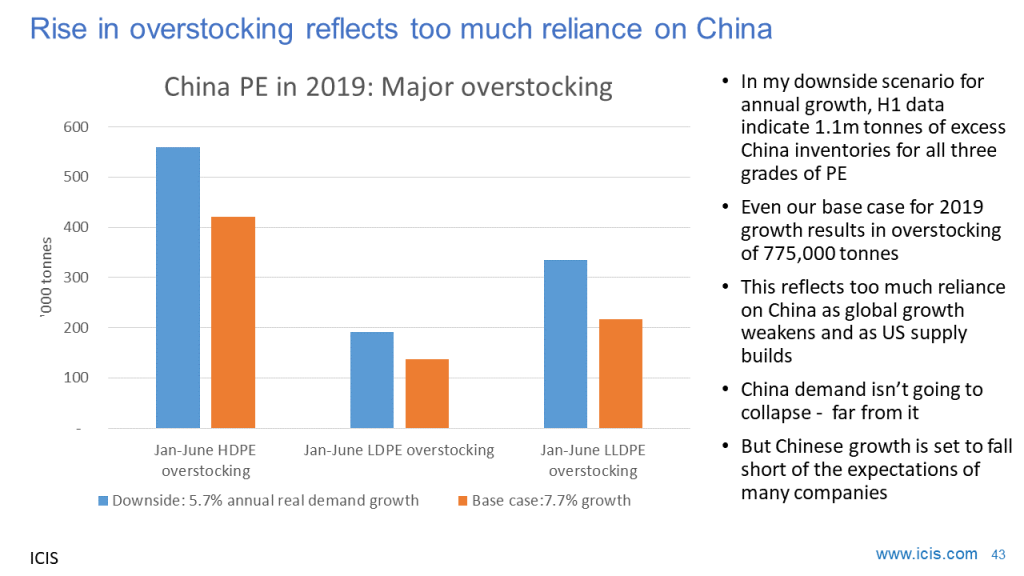

EVEN IF our base case growth rate* for PE in China in 2019 proves to be correct the H1 data still suggest excess inventories of 755,000 tonnes (click here for a post explaining the methodology).

As the China economy further decelerates due to the trade war and domestic economic problems, I believe that the the 2019 growth rate is more likely to average 5.7% for the three grades of PE compared with our base case 7.7%. This would leave overstocking in H1 at 1.1m tonnes compared with my estimate of just below one million tonnes in January-May.

Breaking down the data to the three grades of PE reveal some quite startling H1 numbers:

- In HDPE, local production was up by 22% year-on-year with net imports 14% higher. This indicates apparent demand growth of 18% (apparent demand is local production plus net imports before adjustments for inventory distortions).

- LDPE production rose by 3% with net imports 15% higher, resulting in an increase in apparent demand of 9%.

- LLDPE production increased by 5% with net imports no less than 24% higher. This equalled a 12% increase in apparent demand.

This left average H1 apparent demand growth at 13% across the three grades. Even though PE growth has to some extent decoupled from GDP, does this feel like a market increasing by 13%? I think not. The last time annual growth reached 13% was during 2013 when the economy was in a lot better shape.

Spreads between CFR Japan naphtha feedstock costs and China PE prices remain at their lowest level since 2012. This is despite naphtha costs being much lower than in 2012. This tells us that PE producers lack pricing power. Supply in excess of demand must be the cause of their reduced profitability and not high raw material costs.

All of this implies a prolonged period of destocking as excess China inventories are absorbed.

*Our annual growth rates are “real growth”, where adjustments are made for inventory distortions.

Why we can longer depend on stimulus

Time again in circumstances like these China has returned its economy to extremely robust growth by major doses of fiscal and monetary stimulus. Not this time, I’m afraid.

The H1 local production and net import data on HDPE implies a big bet on the above happening again, via spending on infrastructure. This would boost demand for HDPE into water and gas pipes and electrical conduits.

On the surface, it seems as if an infrastructure spending boom is about to take place. Local government “special-purpose” bond issuances (it is the provincial governments that carry out infrastructure spending) was at 2.8 trillion yuan in H1, double the amount in the first half of 2018.

But these bonds have only partially replaced the big reduction in the availability of shadow, high-risk financing, which the local governments used to regularly tap into. In H1 2019 compared with the first half of last year, shadow lending was down by $133bn, according to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) data. The PBOC is China’s central bank.

Further, the special purpose bonds carry the condition that if they are used to fund infrastructure spending, projects must return enough revenues to service the bonds, says the Chinese financial magazine, Caixin. Previously, shortfalls could be made up by money from general local government revenues. This is causing hesitation to invest.

There is evidence that provinces are running out bridges, roads and railways to invest in – an inevitable result of huge infrastructure spending over the last 10 years.

A further difficulty for the local governments is the Yuan 2 trillion worth of tax cuts, mainly comprising reductions in VAT, which Beijing introduced from 1 May in an effort to boost consumer spending. The tax cuts have sharply reduced local authority revenues.

In the first half of 2019, fixed-asset investment, excluding spending in rural areas, rose by 5.8% year-on-year, lower than the 6% increase in the same period in 2018. Infrastructure spending was up by 4.1% down from a 7.3% pace and 21.1% in H2 2017, writes Caixin.

And not surprisingly given the trade war, manufacturing investment performed the worst. It was up by just 3% in H1 as against 10.9% in H1 2018.

If we can’t depend on infrastructure spending and investment in manufacturing to lift the economy out of the gloom, what about the famous Chinese consumer? Won’t all those tax cuts encourage the one billion-plus consumers to go out and spend lots of money? You might argue that this is what really matters as in H1 of this year, two-thirds of China’s GDP growth came from consumer spending.

Consumer spending expected to slow

Sales of “big ticket” or expensive items, such as cars and housing, have been slowing down since Q1 because of the economic anxiety provoked by the trade war. Now, of course, the trade is getting worse.

This is confirmed by a PBOC survey: “A survey by China’s central bank last week showed that 79% of respondents wanted to save money rather than spend it,” says the South China Morning Post.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch forecasts that growth in consumer spending will decline in July, including possibly even e-commerce sales now that major promotional events are out of the way. The rapid rise in e-commerce has been a major factor behind the recent stellar performance of the China PE market.

The May tax cuts have done little to boost consumer spending, according to Nomura Bank. This further supports the argument that the trade war is having a very negative impact on consumer confidence.

Sure, China might throw the proverbial kitchen sink at lower economic growth, which is the consensus opinion. This would temporarily boost GDP and help consume PE sitting unsold in inventories.

But, as I said, infrastructure and manufacturing investment seems to be going nowhere, with a recovery in consumer confidence depending on a quick resolution to the trade war. As they say, “Good luck with that”.

And can China really afford to throw the kitchen sink at consumer spending? In 2008, consumer debt-to- GDP was 18%. By the end of 2018, it had surged to 53%. This compares with the 40% average for other developing countries. This reduces Beijing’s room for manoeuvre.

Consumer confidence doesn’t just depend on the trade war. Also crucial is maintaining inflation of the property bubble. But the government’s room for manoeuvre is limited here as well, because most of the rise in consumer debt is down to buying second, third or fourth etc. homes as investments. Half of all new-home sales are of second, third or fourth etc. properties, resulting in oversupply in some cities.

The over-exposure of corporate lending to the real estate sector is another issue. This was highlighted by the decision of Evergrande, China’s largest real estate developer, to issue IOUs to its creditors because it can no longer afford to pay its bills.

Here is another problem relating to real estate: “In first-tier cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen, the price to income ratio has risen to 50+. In other words, in these cities, it would take someone earning the average salary fifty years saving 100% of their income to be able to purchase an average-priced home”, writes financial website, Seeking Alpha.

In the current climate, even hesitation by Beijing in launching a major wave of stimulus might be enough to perpetuate the slowdown. But the evidence above suggests that the Chinese government might simply be unable to launch a big-enough stimulus programme.

Conclusion

This is not the end of the world as we know it. The Chinese economy, even in the likely event of a global recession, isn’t going to collapse. The problem will instead be lower demand growth for PE and other petrochemicals than most global producers have budgeted for.

In the case of PE, my forecast 5.7% growth rate would still be very healthy relative to most of the rest of the world. A big new volume of demand would also be created because of the size of the China market.

But the H1 data clearly show that far too much is being asked of China at a time of rising global production and a weakening global economy.