The views below are my own, and, as always, do not express the opinion of ICIS

By John Richardson

REGARDLESS of your politics you should worry about Donald Trump’s claim that the trade war is hurting the Chinese economy and that the US is therefore winning. For reasons I shall is explain in this post, I believe we will all end up as losers if his approach continues.

Let’s first of all deal with the president’s claim that China is in economic peril because of the trade war. The data suggest otherwise.

Chinese total exports grew by 3.3% year-in-year in dollar terms in July. Between July 2018 and end-June this year, US exports to China crashed by $33bn or 21%. Meanwhile, Chinese exports to the US grew by $4bn – a 1% increase.

This doesn’t take into account transhipments, the billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese exports that flowed through countries such as Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines in order to avoid US tariffs on Chinese goods.

This reflects China’s vast export-focused manufacturing industries. Despite being hampered by rising labour costs, its industries enjoy excellent logistics and product quality and consistency advantages over rivals. Hence, US consumers still prefer Chinese goods despite the tariffs.

The facts on the ground are quite startling. In 1998-2001, the US had a 21% share of global manufacturing production with China at 6%. The US had a 16% share in 2016-2018 with China at 24%. It feels to me as if the US is trying to bolt the proverbial stable door after the horse has already bolted.

Trump is right about the slowdown in the overall Chinese economy which was evident from a slew of disappointing July data. Aside from strong export growth, China’s growth in industrial production fell to a 17-year low in the year to July. Retail sales and fixed-asset investment growth also declined.

But these declines are more down to domestic economic problems than the trade war

It was never going to last forever

First we had the export-focused economic boom in China from 1978 onwards following Deng Xiaoping’s “opening up policies”. The boom was turbocharged by China’s admission to the World Trade Organisation in 2001 as quotas and tariffs that restricted China’s exports to the West were removed. China was able to take maximum advantage of its rising working-age population.

Now the working age population is shrinking as China’s population rapidly ages. But no matter. Since 2009, Chinese growth, and with it global growth, has been hugely boosted by the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus programme. This has created a huge rise in consumer spending.

It is worth noting that two thirds of Chinese growth in H1 this year was down to domestic spending. But this period of growth has left behind a major bad debt problem.

Factories were built for the economic multiplier effect from 2009 onwards in order to compensate for the Global Financial Crisis. This has led to oversupply in many industries, including some petrochemicals, and a heavy burden of corporate debt. Investment in new basic manufacturing capacity has understandably slowed down.

Infrastructure spending also went through the roof in the post-2009, again for the sake of the economic multiplier effect.

Local governments have run out of bridges, roads and railways etc. that are worth building, so saturated is China with infrastructure. Changes in financing rules are also making provincial governments reluctant to spend money on more infrastructure. A further problem for local authorities, which are the main driver of infrastructure spending, are tax cuts that have reduced their revenues.

“But what about the 2 Trillion Yuan tax cuts that were introduced in May? Haven’t they boosted consumer spending?” you might say. No. Here is where the trade war does come into the picture. China’s consumers are less willing to buy autos, houses and other big ticket items because the trade war has made them worried about the future.

Beijing’s hands are tied on the extent to which it can boost consumer spending. Consumer debt had risen to 53% of GDP by the end of 2018 from just 18% in 2008. This is very high for a developing economy.

One of the reasons why China has cut back on the availability of shadow, or high risk lending, by $133bn year- on-year up until June this year is to control the growth in consumer debt. A further reason was to cool the property market, with the extraordinary bubble in real estate a major reason for the rapid growth in consumer debt. And it is in turn rising property values that have led to the big boom in consumer spending.

We have to worry about the real estate sector:

- China’s banking sector has up to 55 trillion RMB ($8 trillion) exposure to real estate or real estate-related loans.

- Half of all home purchases are to second, third, fourth, etc. home buyers, who obviously buying for investment purposes. An indication of low occupancy rates is the 14% decline in furniture sales between July 2018 and July of this year. Furniture sales in June-July were one third lower than during the same period in 2017. This helps explain why China CFR mono- ethylene glycols (MEG) spreads over CFR Japan feedstock costs are so far this year at their lowest level since at least 2000. MEG is used to make polyester that goes into furniture coverings and mattresses and pillows etc.

People have been warning about the real estate bubble coming to an end for a long time. But this now feels like the end-game, a sign of which are the problems at teal-estate developer, Evergrande. The New York Times writes:

“Evergrande is China’s largest and best known property company. By the end of last year it had issued nearly $20bn worth of IOUs to its suppliers. With a towering $100bn debt pile and a penchant for raising bonds to pay off the interest, it appears to have turned to commercial acceptance bills to help cover costs.”

The fact that Evergrande has to write IOUs because it cannot afford to pay its bills indicates stress in the real-estate sector.

China’s role in driving global PP consumption

China’s role in driving the global economy, and thus in driving petrochemicals and polymers demand, has been so huge, so pivotal, that even marginally weaker growth in China will have major negative consequences.

Let’s take PP as an example. We have forecast annual 2019 Chinese demand growth of 6%. This is on track not to happen as growth during H1 was only 4%. This implies consumption by the end of this year at no less than 679,000 tonnes less than we have forecast.

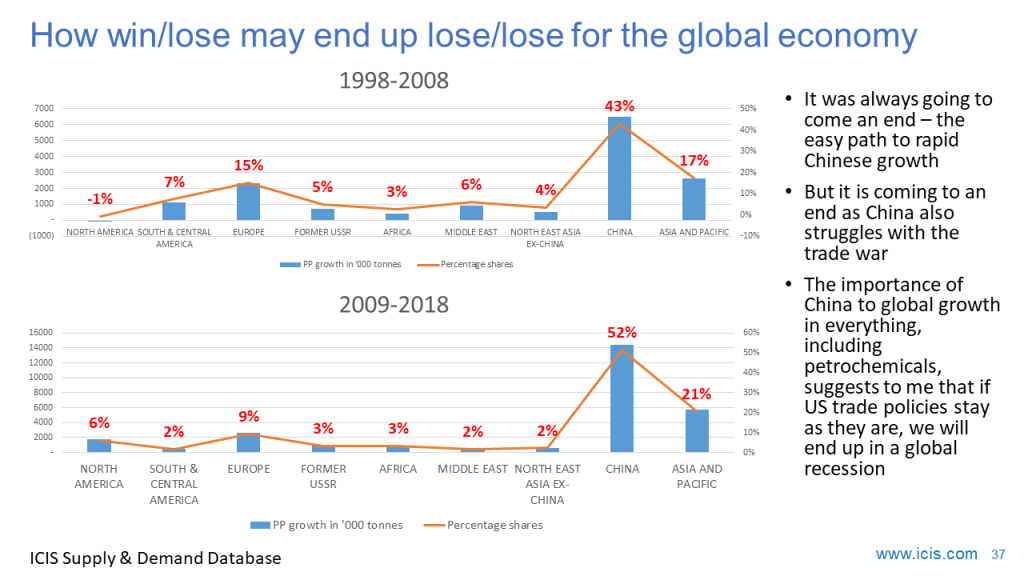

Also take a look at the above charts that indicate the role that China has played in driving the growth of PP demand since 2000 (in terms of actual volumes, it became the biggest global consumer amongst all the other countries and regions in 2009, overtaking Europe).

The charts show two distinct nine-year periods: 1999-2008 when China began to benefit from WTO membership and 2009-2018 when debt and consumer spending became bigger drivers of the economy.

We see China accounting for 40% of global growth in 2009-2018. Take just a few percentage points off this share, and, given the links between China and the rest of the global economy, the damage would be severe.

Conclusion

There are of course legitimate concerns about China’s intellectual property rights protection. Absolutely as well, the US needs to protect its economic and geopolitical interests as China continues to rise.

But confrontational approaches rarely come to any good in international relations and confrontation with China, as it struggles to deal with very severe domestic economic problems, carries major risks.

In my view, therefore, unless the US changes its approach I see a global recession as almost inevitable.

The severity of a recession would depend on the ability of politicians and central bankers to work together, as they did so effectively in 2008. In the current febrile climate this kind of cooperation seems very unlikely.