By John Richardson

US BUSINESSES are making arrangements to diversify their supply chains away from China because of a recognition that, even if a short term trade deal is done, the long term trajectory is towards a much more confrontational relationship between the US and China, says Jacob Parker, vice president of China operations at the US-China Business Council.

This makes perfect sense for some US manufacturing value chains. But, when it comes to the polyester value chain, the US is likely to face some major challenges in achieving this objective. In fact, one could go as far as to say, “Good luck with that”.

A recently as 2000, China only accounted for 35% of global polyester fibres demand, according to the excellent ICIS Supply & Demand database. But by last year this had reached no less than 71%. We see China’s dominance of global demand edging up even further, to 73% by 2030.

Most importantly for the US ethylene glycols industry, China has switched from being a net importer of polyester fibres being a major exporter. This has resulted in it assuming much greater global importance as an importer of glycols given that it is struggling to significantly raise its self-sufficiency in the polyester raw material.

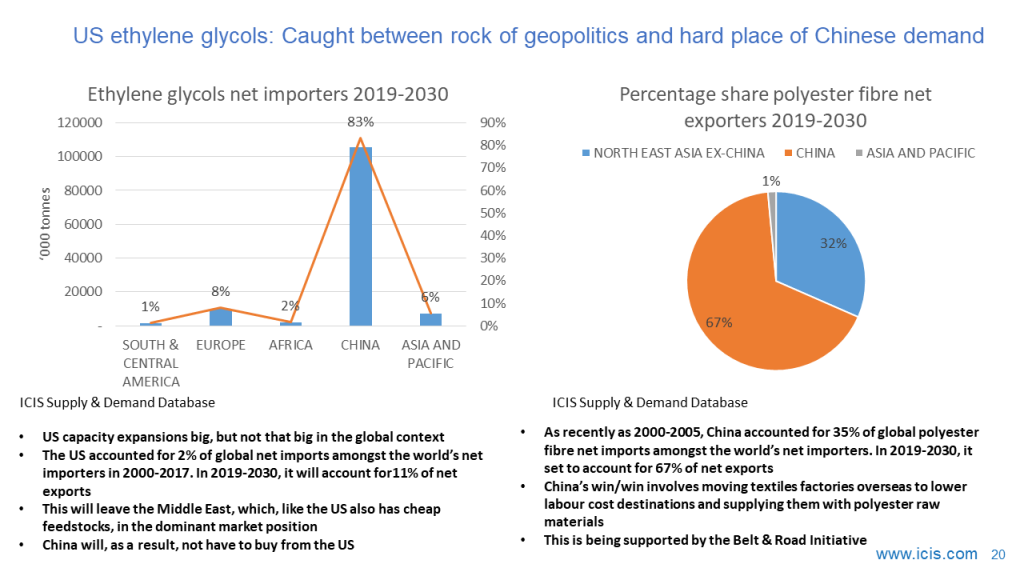

Between 2000 and 2005, China was responsible for 35% of global net imports of polyester fibres amongst the world’s net import countries and regions. The following year was the tipping point as China moved into a very slight net export position, with exports increasing ever since. From 2019 until 2030, we expect China to account for 67% of global net export amongst the world’s net exporters.

As I said, this will has major implications for China’s importance as a driver of global ethylene glycols imports (note that our data includes di and tri-ethylene glycols, as well as mono-ethylene glycols. But, of course, the vast majority of the market is mono-ethylene glycols for polyester production). Earlier this century, China accounted for around 50% of global net ethylene glycols imports, once again amongst the world’s net importers. Between 2019 and 2030 this will rise to no less than 83%.

China’s “win/win” approach to the textiles industry

China is losing its ability to compete in low value apparel and non-apparel manufacturing because of rising labour costs. No matter. It is moving its factories overseas to cheaper labour cost locations and is supplying the polyester raw materials because, as I said, it is in a big export position. Countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia, where I hear some four out of ten clothing factories are under Chinese ownership, don’t have enough of their own polyester capacities.

This is a win/win. China gets to keep control of a vital manufacturing value chain. Even though jobs are being lost in China as textiles mills close down, at least China’s textiles entrepreneurs are still able to make money.

Meanwhile, countries such as Bangladesh which have youthful populations are benefiting from increasing employment. This win/win is further underpinned by China’s investment in bridges, roads, railways, power plants and other infrastructure in the developing world as part of its Belt & Road Initiative.

The question for China then become where it buys its ethylene glycols from. Along with paraxylene, China will also said, need many tonnes of imports for at least the next decade or so.

In January-August of this year, after many years as a net importer (exports minus imports), the US moved into a slight net export position in glycols as it ramped up its capacity. New capacities are part of big new steam cracker complexes which downstream primarily make polyethylene, but also make considerable amounts of ethylene glycols.

But despite the significant US capacity build-up, relatively speaking the US will remain a small player. It will move from holding a 2% net import share of global net ethylene glycols imports in 2000-2017 to an 11% of net exports in 2018-2030. The Middle East will remain by far the biggest export player.

As a result, the US will lack major pricing power compared with the Middle East because its low market share. Further, the Middle East, like the US, enjoys very strong feedstock advantage.

China will of course have the biggest buying power. It can choose to buy glycols only from the Middle East. In parallel, I also expect China to push much harder towards ethylene glycols self- sufficiency than our base case assumes through both the naphtha route and the improved efficiency of its coal-based production.

Fitting US ethylene glycols exports into other markets

Conversely, though, you can argue that because the US capacity build is not such a big deal in the global context, the US will comfortably be able to place its exports in markets other than China. If it ends up flooding these smaller markets, producers in these markets will be able to compensate by exporting more to China. This is how it has worked so far in polyethylene.

But such an outcome will, in my view, only be possible if the US ends up on good terms with the Asia & Pacific region, which includes south Asia and Southeast Asia, and Europe. They will respectively account for 6% and 8% of global net imports of ethylene glycols – again amongst the world’s net importers – between 2018 and 2030.

Can the US end up on good terms with Asia & Pacific and Europe? Much might depend on whether the US can match China in overseas investments in infrastructure which raises economic growth in poor countries. But would this increased spending fit with the current White House “America First” approach?

The US is keen on reshoring basic manufacturing instead of moving it overseas, as China is doing. And, anyway, US textile mills have largely already shut down. So it cannot relocate textiles production to say Bangladesh.

I see a situation where China pulls much of Asia & Pacific closer into its economic and geopolitical orbit and perhaps Europe as well, creating the world’s biggest ever free trade zone, with the US outside this zone. Where would the US then export its glycols to?

This is only one outcome. The bipolar world I’ve talked about before, where China emerges as the winner over the US, is just one scenario. You may strongly disagree and you have devised your own scenarios. But we are clearly in a very different world where geopolitics counts as much, if not more, than feedstock advantage in determining the pattern of petrochemicals trade flows.