As always, these are my personal views and don’t reflect the views of ICIS

By John Richardson

IT IS A polyethylene (PE) world turned upside down which, in my view, will remain upside down. With oil prices set to stay around $30/bbl over the long term, the US ethane advantage is in my opinion pretty much gone for good.

Even if I am wrong and oil prices recover to pre-coronavirus crisis levels, the social and political landscape will be redrawn to such an extent that the US will still find its ability to export to most of the developing world badly undermined.

Expect, as I discussed earlier this month, a China-led economic and geopolitical bloc comprising much of the developing world. We were already heading in this direction before the coronavirus outbreak.

Now the worsening US and China relationship over who is to blame for the virus, if anyone is to blame, is pushing us more rapidly in the direction of a bipolar world of two competing blocs – one led by the US and the other by China.

The US will, I believe, find itself facing high tariff barriers if it wants to export anything to the China-led bloc.

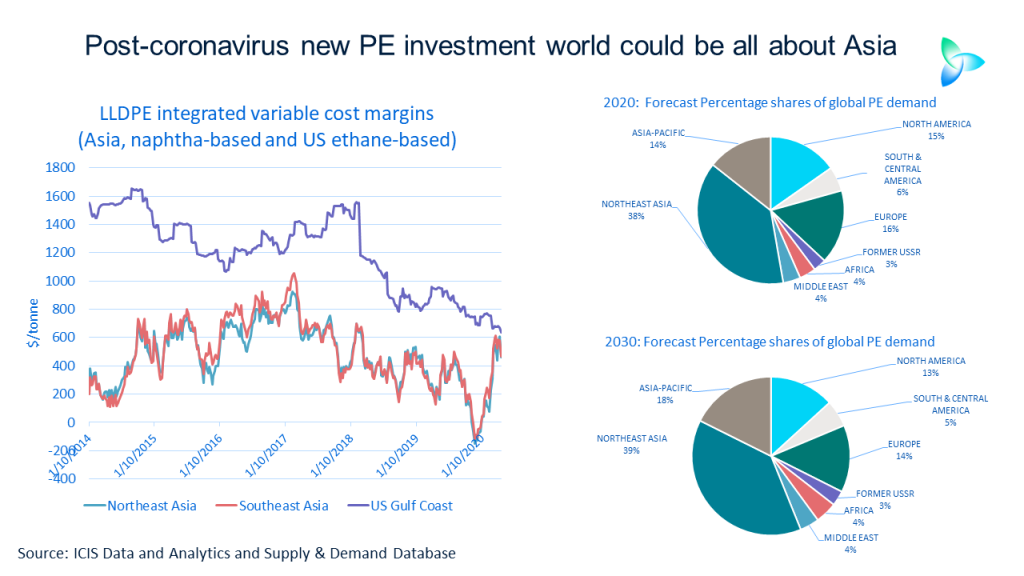

Without the ability to easily access developing markets, and as demand in the developed world will form a smaller part of the global pie (see the above charts), I see little justification, if any, for further US investments that are not already under construction.

What about the existing plants given that the US has invested so much money into such large amounts of new capacity, most of it targeted at exports because of low-growth in the US market?

These plants will run hard because of the need to get rid of ethane. For safety reasons, you can only leave a small percentage of ethane in methane that is delivered through domestic pipelines.

The only end-use market for ethane is steam crackers. Existing assets will therefore be run hard even when returns on PE investments are way below expectations.

This is clear from the US export data for January and February 2020, which is the latest data I have available. The data shows that even in today’s low oil-price world – where as the chart above illustrates, the US ethane advantage has just about disappeared – US exports surged.

Total US linear-low density PE (LLDPE) exports rose 45% year on year, with high-density PE (HDPE) exports 38% higher.

Interestingly, China customs data also show that LLDPE and HDPE imports from the US were each up by around 20% compared with the same period in 2019 during the whole of Q1 This reflected the Chinese decision to allow importers to apply for exemptions on the additional import tariffs China imposed on US PE as part of the trade war.

But I see this as a temporary thaw in the relationship between the US and China. Comments last week by President Trump and Larry Kudlow, White House Economic Council director, point in the direction of the trade war intensifying again. And, as I said earlier, long-term trends that have been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic were already leading us towards a bipolar world.

The new investment landscape

I have long felt that cost curves, which measure the efficiency of existing and future plants based on cost of production per tonne, only tell part of the story.

You must extend the economic envelope beyond just the gas-to-petrochemicals complex or the refinery-to-petrochemicals complex. What also needs to be considered are the wider economic benefits that a petrochemicals complex delivers to a country.

Even if I am wrong about oil prices being around $30 a barrel over the long term, Asia will still be the main location for new cracker investments once the coronavirus pandemic is over, because of the wider economic benefits.

In a country such as Vietnam, for example, unannounced refinery-cracker investment may happen in order to add value to local oil supplies and create local jobs for local people.

Another factor driving new investments in Vietnam could be its economic relationship with China. As China’s population rapidly ages, we may see a further drift of low value finished goods manufacturing from China to Vietnam.

The relocated manufacturing would benefit from local PE supply, with the PE in excess of local demand exported to China as China is set to remain in a long-term big deficit on PE.

In China itself the logic for building petrochemicals plants has always been far wider than the conventional cost-curve analysis. Downstream job creation has always been, and will continue to be, a critical factor. Import substitution will also remain important as China pushes closer to self-sufficiency.

But it seems very unlikely that China will hit either PE or ethylene glycols self-sufficiency over the next decade. I believe this will support the rationale for new investments across Asia that will boost local economies with surpluses exported to China.

One other non-cost-per-tonne factor is the role of the state-owned companies in Asia. Sinopec and PetroChina are the most obvious examples, but also think of Petronas in Malaysia and PTT Global Chemical in Thailand.

These companies of course want to make money and do make money. But their investment decisions can also involve the agenda of wider national economic development.

Add to this my prediction that most of Asia will end up the China-led economic and geopolitical bloc – ensuring low or no tariff petrochemical exports to China – and the justification for Asian investments in the post-coronavirus world will be strong.

If am right on crude, and as naphtha cracking will remain dominant in Asia, then of course $30/bbl crude will add further support to a new wave of Asian investments.

Where does the Middle East fit into this new landscape? Like the US, it has of course lost its ethane advantage, and this will remain the case if my prediction of a long-term price of $30/bbl for oil comes true.

The Middle East will face a difficult choice of either aligning itself with the US bloc or the China bloc. Countries in the region that choose China will enjoy preferential access to its petrochemical markets, with petrochemicals quite likely exported to China as a package with oil.

Yes, I could be wrong, it has been known. All the above is, as always, open to debate and ready to be challenged. There are many other potential outcomes. But what is surely clear to all of us that there can be no return to the pre-virus petrochemicals world.