By John Richardson

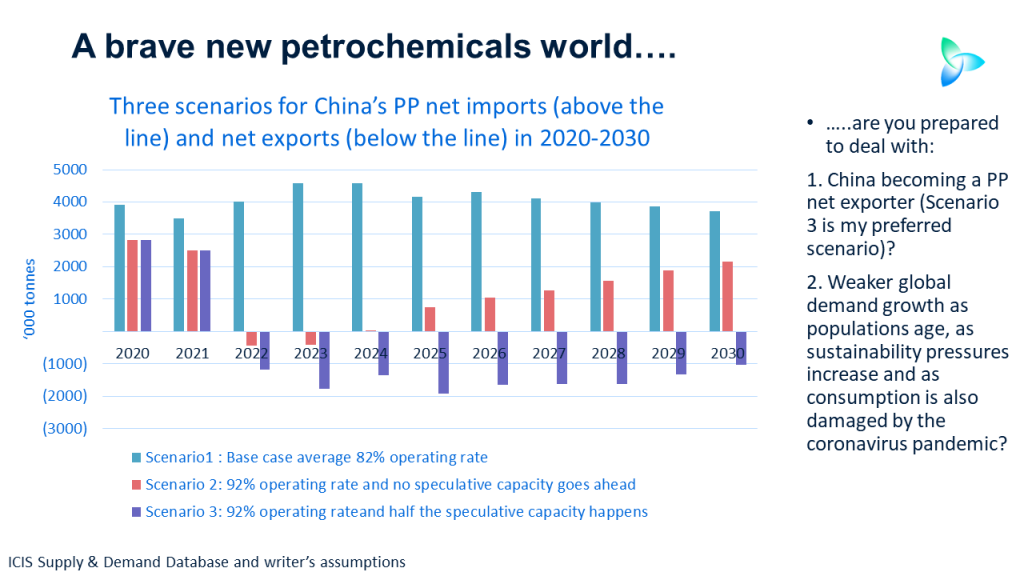

SORRY to labour the point but this comes from a genuine concern for the readers of this blog, including many of our valued ICIS customers: the above chart, if you have been following the blog over the last six years, should come as no surprise.

You may, as a result, already have strategies in place to diversify your polypropylene (PP) exports away from China.

Your company might have also adapted your approach in line with another key theme of the blog over the last nine years – declining PP demand growth (this applies to all petrochemicals and polymers). As the 55+ demographic cohort expands in size, spending on all the things made from PP will start to fall below consensus expectations.

We now have the added dynamic of the biggest economic crisis since at least the Great Depression. Nobody saw this coming, but it is what it is and we have to deal with it. This will add to the loss of demand growth for all things made form PP that will occur because of ageing populations.

PP companies need to contend with the rise of the Millennials and an environmental consciousness that exceeds a good number of my fellow Babyboomers. The Millennials are of course the future. It will be a great future if we can tackle the environmental challenges of climate change and plastic pollution.

This means that washing machines and automobiles etc. made from PP will be owned for longer as we move away from the old throw-away society. In the case of automobiles, I believe they will not be owned at all by many Millennials as autonomous driving develops.

Before the pandemic, environmental consciousness among Millennials was the main factor behind a desire to own things for longer – to buy fewer new things. Now we also face the huge wealth and income losses caused by the pandemic.

The growth of the recycling industry has been held back by coronavirus as people confront more immediate worries. So have schemes to collect and sustainably dispose of plastic rubbish, especially in the developing world.

But I believe that the issue of plastic pollution will come roaring back because of the attitudes of the Millennials. This will further limit our ability to build new PP plants that make virgin resins, given that some 30% of global PP demand is from single-use packaging.

“But what about the rise of demand in the developing world?” I hear you ask, “surely, the dynamics are different here as people rise out of poverty and are able to afford modern-day consumer goods made from PP for the first time.”

Absolutely. I entirely agree. But there are no scenarios under which PP demand in the rest of the emerging and developing world can come anywhere close to rivalling that of China’s over the next decade. The pandemic has also set back growth in poorer countries by at least five years, probably more.

China’s demand also entirely dominates the global picture. In 2010, China’s PP demand was just 10% of the global total at 4.6m tonnes, according to the ICIS Supply & Demand Database. In 2020, we expect this to reach 29.6m tonnes and 39% of the global total. China’s consumption by 2030 is forecast to again account for 39% of the global total, reaching 45.7m tonnes.

If you add together Asia-Pacific, Africa and South & central America, this is what you find: In 2000, the regions accounted for 16% of the global PP total – 4.7m tonnes of demand. They are forecast to reach 12.6m tonnes and 23% in 2020 and 34m tonnes and 28% in 2030.

Because China will continue to dominate global PP demand, and because it will struggle to produce enough local PP to meet its demand, our base case (Scenario 1 in the above chart) forecasts that the country will account for 42% of total global net imports in 2020-2030. This would be 44.8m tonnes of net shipments to China – i.e. minus a small volume of exports.

In second place would be Europe (we include Turkey in Europe) at 37% and 39.8m tonnes followed by Africa at 12% and 12.4m tonnes and South and Central America at 10% and 10.6m tonnes.

I disagree as I see China moving to complete PP self-sufficiency. What applies to PP will also apply in varying degrees to paraxylene (PX), styrene monomer (SM), ethylene glycols and polyethylene (PE). I dealt with scenarios for China’s rising PX self-sufficiency in my post on Monday and I’ll look at the other products later on.

Drilling down to PP: A close look at the scenarios

The turning point was, as I said earlier, six years ago when my contacts who are close to Chinese government officials told me that there would be a major push towards much greater petrochemicals self-sufficiency in general.

This was the result of China’s need to move up the manufacturing value chain as it confronted a rapidly ageing population. Another motive was improving the cost efficiency of downstream industries by increasing the availability of local raw materials.

We will therefore this year reach the point where China will have enough steel in the ground to achieve complete PP self-sufficiency.

But our base case forecasts China will still need to import between 3.7m tonnes and 4.6m tonnes of PP per year in 2020-2023, as average operating rates will reach only 82%.

I foresee a different outcome as producing PP in China isn’t just about making money at the individual plant level. The type of national objectives outlined above heavily influence production decisions, which is why I think operating rates in 2020-2030 will be higher.

Also consider the new dynamic of rising geopolitical tensions between not just the US and China but also between China, the EU and other countries and regions. China can no longer depend on the kindness of strangers in a world where globalisation could so easily go into reverse.

If the country runs its PP plants at too-low operating rates, it may not be able to source enough PP from overseas to keep washing machine and auto factories open. Preventing job losses has long been a top priority of the Chinese Communist Party.

The need for greater self-reliance was highlighted earlier this month, in an important speech by China’s president, Xi Jinping. He told an audience of top government officials in Beijing that there was a need for more self-reliance because of a trade war and technology rivalry with the US, and an expected fragmentation of the global economy following the coronavirus pandemic.

This leads me to my two alternative scenarios for China’s PP balances in 2020-2030:

- Scenario 1 involves an average operating rate of 92%, two percentage points higher than average capacity utilisation in 2000-2019. This would result in China swinging into small net export positions of around 400,000 tonnes/year in 2022-2023 before net imports climb to 2.2m tonnes in 2030.

- But my preferred scenario is Scenario 2. Here I again assume an operating rate of 92% and include 50% of the new capacity we have listed as unconfirmed. I believe China will add a considerable sum of yet-to-be-confirmed capacity over the next 10 years. China would remain in a net import position in 2020-2021. But in 2022-2030, net exports would range from 1m-2m tonnes per year.

Note that for all these three scenarios I have kept to our base case of Chinese PP demand growth, which is an average 4% per annum between 2020 and 2030. But for the reasons highlighted above, demand growth in China could be lower than this. The expansion in consumption across the rest of the world may also fall below our base case.

These outcomes would not deter China from running its existing PP capacity hard or adding a lot of new plants because of the strategy of greater self-reliance.

As I said at the beginning, these trends haven’t happened overnight, they have been in play for years. The PP company you work may have already responded by building an entirely new business model. If this hasn’t happened, there is no more time to waste.