By John Richardson

AFTER a very challenging first quarter, nobody wants to make further write-downs on the value of raw materials and finished-product inventories. But this is the risk for any polyethylene (PE) producer who believes the recent rallies in equity markets and oil prices are leading indicators for the strength of the real economy.

China is, at the very best, going to achieve 1.5% to 2% GDP growth this year as a new wave of infrastructure spending attempts to counteract the collapse of export orders. A huge hole in its economy was left by negative Q1 growth of at least 6.8%.

The US, as we all know, is experiencing major social unrest that could add to the economic damage caused by coronavirus pandemic lockdowns. The economic damage was already huge before the unrest began: The Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank published an estimate, before the protests, of a 51.2% year-on-year fall in US GDP in Q2. This is not a typo – a 51.2% fall.

In no country can we be sure that the emergence from lockdowns will be entirely smooth.

In the UK, scientists have warned that social distancing rules are being eased too soon. What’s very worrying is that the warnings have come from scientists who advise the government.

Lockdowns in the developing world may have been relaxed too soon because of the pressure to get “day rate” labourers back to work. People living on just a few dollars a day must work every work every day to feed themselves and their families. Social distancing restrictions made this type of work impossible.

Nobody knows the real number of deaths globally without which it is impossible to accurately assess the mortality rate. Just as unclear are the number of asymptomatic carriers and the effectiveness of antibodies built up in the bodies of those who have caught and recovered from coronavirus.

And yet a quick glance at US equity and crude markets gives the impression all will be soon right with the world. But as the weekly PH report says, the strength of the S&P 500 is down to the importance of the six FAAANM stocks (Facebook, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Netflix, Microsoft), which have tripled since 2007 and are already back at their pre-lockdown peaks.

What happens if the damage to Main Street in the US (remember that 51.2% forecast decline in Q2 GDP growth) leads to a contraction in advertising revenue? The FAANMs might then weaken.

Stock markets elsewhere have also recovered from their coronavirus lows, including in Asia, even though there is another risk to consider: A reignition of the US/China trade war in the run-up to the November presidential election.

A further factor behind the rebound in equities and oil prices is an expectation of a recovery in consumer spending as lockdowns are relaxed.

But we must put the recoveries in the context that normal economic activity was virtually impossible at the high points of lockdowns. In the UK, for example, car sales in April were down by 97% on a year-on-year basis. Sales in May will inevitably be better because showrooms are reopening. This won’t mean that UK auto sales will in May onwards return to anywhere close to their normal levels.

Global demand for just about everything cannot quickly return to pre-crisis levels because of the scale of wealth and income losses. The Congressional Budget Office predicts it will take ten years for the US economy to fully recover.

Oil demand cannot recover all the ground it has lost in 2020, no matter how successful the emergence from lockdowns. The latest EIA forecast (the next one is due out on 9 June) is for global liquid fuels consumption averaging 92.6m bbl/day in 2020, down 8.1m bbl/day from 2019.

Storage also remains a big issue. Bloomberg writes: “World supply probably exceeded demand in the first half of 2020 at an average rate of about 5.5m bbl/day, causing inventories to balloon by just under 1bn barrels, according to consultants Rystad Energy A/S in Oslo. Citigroup Inc.’s estimate is a fraction higher.”

If half of the billion-barrel excess ended up in storage, stockpiles would easily be above the all-time record-high of 3.13bn barrels in 2016, calculates the wire service.

The mistake many PE producers made in Q1 was they assumed oil prices could not go below $10/bbl, never mind into negative territory (don’t say I didn’t warn you). I believe there is every chance of another collapse in crude prices for the reasons outlined above.

Drilling down to PE market specifics

Data on the PE market, in my view, also point to long global PE markets over the next few months, barring unannounced production cutbacks.

China’s PE production increased by 9.1% in January-April 2020 on a year-on-year basis, much higher than our base case forecast for full-year production growth of 3%.

I believe China will run its new PE capacity much harder than consensus opinion suggests because this is the last year of the 13th-Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). Companies must hit production targets set at the beginning of the plan. China’s new capacity is also far to the left of the cost curve and thus very cost-efficient. The same applies to China’s new PP capacity.

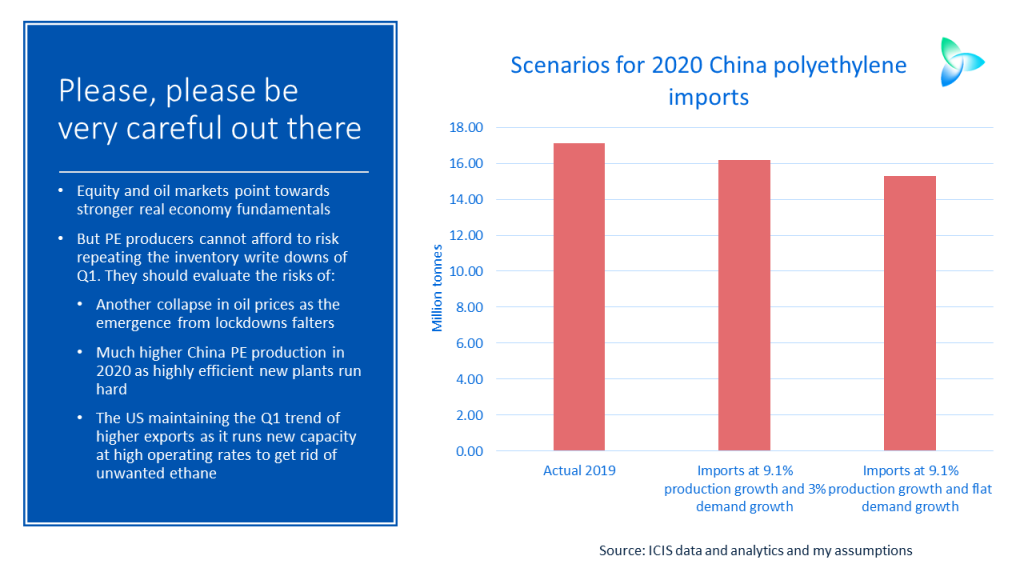

For argument’s sake, let us assume full-year PE production growth reaches 9.1% and demand growth is in line with our base case of 3%. This would result in total PE imports falling to 16.2m tonnes from last year’s 17.1m tonnes.

But I believe there is a good chance that PE growth across the three grades will average less than 3% as the Chinese recovery may not be as strong as the official numbers suggest. Let us assume zero growth and leave the increase in production at 9.1%: Imports would fall to 15.1m tonnes.

I expect 2020 global PE consumption will be around 104m tonnes compared with our pre-crisis forecast of 112m tonnes.

PE has benefited from panic buying in supermarkets. But I am sticking with my contention that the sheer scale of lost economic activity must be bad news for global PE demand. Growth will be, I believe, at least as weak as in 2008 – during the Global Financial Crisis.

Remember that the 2008-2009 crisis was essentially over in a couple of quarters, thanks in large part to China’s economic stimulus programme. China cannot afford another programme on the same scale because of its bad-debt problems. And, quite obviously, the pandemic will last a lot longer than two quarters.

New US PE plants, like their Chinese counterparts, will run very hard for the rest of this year regardless of their margin position and the state of demand.

US Gulf Coast variable-cost margins have collapsed because of the decline in oil prices.

But US PE producers integrated upstream into natural gas (methane) production must get rid of their unwanted ethane by turning it into ethylene and then PE (ethylene production is the only end-use market for ethane). They need to dispose of ethane because of safety limits on the amount of ethane that can be left in methane.

In theory, ethane could be burnt or flared, but why burn money when some contribution is being made to the cost of new PE investments, even if contributions will be a lot lower than had been forecast?

Evidence supporting my arguments comes from the Q1 US export data. High-density PE exports were at 1.1m tonnes – 33% higher than in Q1 2019; linear-low density exports were 40% higher than 2019 at 1.4m tonnes. The first quarter 2020 increases came on top of big increases in Q1 2019 over Q1 2018.

I could be wrong of course and equity and oil markets may be good leading indicators of a V-shaped recovery. But I have yet to find any compelling evidence supporting this argument.

And remember that global PE market were tight in December and January following production cutbacks in response to oversupply. This helped support pricing in February-April relative to the collapse in naphtha costs.

As I keep saying, please, please be careful out there.