By John Richardson

IT IS dead simple, apparently. All you have to do is find alternative geographical markets to China as China moves towards petrochemicals self-sufficiency and everything will be fine. In my view there is just one slight problem with this commonly- expressed argument: The data.

The data on every product show that China completely, and I mean completely, either dominates global net imports or global net exports. In the case of where China dominates global net exports, then of course the product is no longer an opportunity for a petrochemicals company whose business model largely rests on being able to ship to China.

The historical context for this is the quite staggering increase in Chinese demand over the last 20 years, as the rest of the world has in relative terms lost ground.

As styrene monomer (SM) is our subject today, in 2000 China accounted for 10% of global demand and was way behind northeast Asia ex-China (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan), which was then the world’s biggest consumption region. But in 2009, mainland China overtook northeast Asia ex-China to become the world’s biggest consumer as its share of global demand jumped to 25%.

This year, we expect China’s share of global demand to reach 35%. In terms of tonnes, we forecast that China will have left the rest of northeast Asia way behind. Northeast Asia ex-China demand is forecast to be 5.8m tonnes in 2020 versus 10m tonnes in China. This pattern is expected to continue so that by 2030, we estimate China will account for 38% of global demand.

China’s local capacity additions, until now, have been unable to keep pace with the growth in demand for some petrochemicals. In 2020, for example, we forecast that China will account for no less than 64% of total global net imports of SM. This is among the countries and regions where imports exceed exports. In terms of tonnes, we expect China’s net imports to reach 2.2m tonnes in 2020 versus Europe in distant second place at 476,000 tonnes of net imports – 14% of the global total.

2014 was a watershed year; it was when the Chinese government decided to move much more aggressively towards self-sufficiency in petrochemicals in order to add more value to the Chinese economy.

The policy shift was formulated in early 2014. At that stage, the preferred route to self-sufficiency was coal-to-petrochemicals as China has the world’s second-biggest coal reserves behind the US. But the collapse of oil prices in late 2014, which eroded the competitiveness of coal-based versus oil-based petrochemicals, made Beijing think again.

Subsequently, as oil price volatility continued, public pressure over pollution also greatly increased, which weighed on the coal-to-petrochemicals industry. So, a major strategic shift was made to focus on oil-based petrochemicals at world-scale start-of-the-art new refinery-to-petrochemicals complexes.

These complexes were built near the coast with easy access to international markets, rather than inland where the coal-to-petrochemicals plants were planned for. It makes sense to build coal-to-petrochemicals plants in inland provinces as this is where most of China’s coal reserves are located.

You therefore have had plenty of time to prepare for the enormous changes about to affect global markets as China shifts to what I believe could be just about complete self-sufficiency in SM, polypropylene (PP) and paraxylene (PX). In certain years during the next decade, I can even see China becoming a net exporter in these products.

A lot will of course hinge on operating rates. It is one thing to build capacity but another thing to run capacity very hard. I expect operating rates in SM, PP and PX plants to be high over the next ten years.

Why spend so much money on new capacity, a lot of which is government money through soft loans and shared infrastructure, only to allow plants to run at low operating rates – and when adding value to the economy remains the priority?

Why, also, remain heavily exposed to imports in a very uncertain geopolitical world where continued open borders are far from guaranteed?

Another reason why SM operating rates could be very high is ample benzene supply. China will, as I said, run its PX capacity very hard, leading to a lot of local benzene availability as reformers are maxed-out to make the mixed xylenes and toluene feedstock for PX.

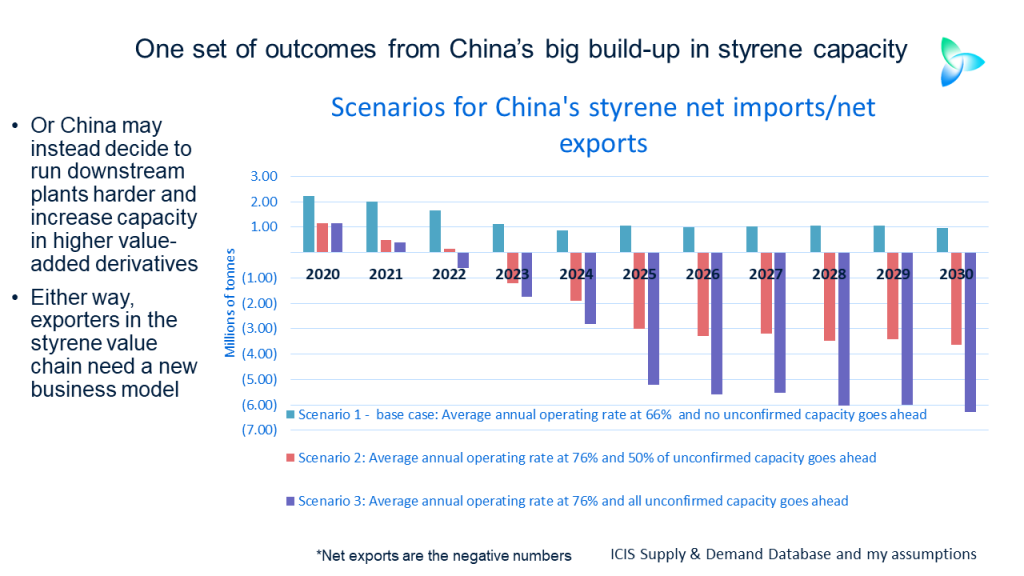

Scenarios for China’s 2020-2030 SM imports

This leads to the chart at the beginning of this post where I present three scenarios for China’s SM imports over the next decade. All the scenarios assume our base case for average annual demand growth in 2020-2030 – at 3% – will be correct:

- Our base case, Scenario 1, sees average 2020-2030 operating rates at 66% with none of the unconfirmed or speculative capacity that we have listed in our ICIS Supply & Demand Database going ahead. Even under this scenario, China’s net imports would see big declines from their historic trends. In 2030, net imports would fall to just 950,000 tonnes.

- Scenario 2 sees half the speculative capacity going ahead and operating rates 10 percentage points higher than the base case, at 76%. In this case, China would become a net exporter from 2023 and in 2030 would export 3.6m tonnes.

- Scenario 3 sees all unconfirmed capacities going ahead and a 76% operating rate. Net exports would begin from 2022 and would reach 6.3m tonnes in 2030.

It may not work out as simply as this of course. Rather than exporting big SM volumes in a global market that may well not be big enough to absorb these volumes, China might instead choose to raise its downstream operating rates. We could see higher polystyrene (PS), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and expandable polystyrene (EPS) operating rates that have in recent years averaged in the mid-70s% range.

China is a net importer of PS and ABS and a net exporter of EPS. We might thus see China swinging into net export positions in PS and ABS and increasing its next export position in EPS.

Derivative capacity additions may also happen, especially perhaps for the higher value-added derivatives, as China again tries to add further value to its economy in a bid to escape its middle-income trap.

This could be bad news for two of the world’s major styrene exporters – Saudi Arabia and Singapore, even under our base case scenario for SM imports. In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s exports to China accounted for 66% of its total SM exports, with all the other destinations in single percentage digits. Singapore was a little more diversified as 52% of its SM exports went to China, with the percentage share of exports to India, Malaysia and Vietnam in double digits.

But Saudi Arabia and Singapore have very limited SM derivatives production. So, unless they add substantial new downstream capacity, they may be in a difficult position.

Japan and Taiwan also have a heavy percentage reliance on mainland China for their export trade. However, most of their SM production goes into local derivatives plants. They would thus be vulnerable if China chooses to boost downstream production rather than to export big volumes of SM.

South Korea, which has a low reliance on SM exports, also consumes most of its SM at home. It would therefore also be exposed if China focused on boosting derivatives output.

What are the solutions for the global petrochemicals industry as China moves to greater self-sufficiency in SM, PP and PX? There are, in my view, three solutions, as I discussed in my post on PP last month:

Localisation of supply chains. Governments around the world don’t want a repeat of the events over the last few months, where there were shortages of personal protective equipment. Government funding will be available to support work with local converters and finished-goods manufacturers in ensuring that there are enough local supplies of face masks and handheld thermometers, etc. Localisation of supply chains will also involve a greater focus on plastics recycling, as making better use of plastic waste will reduce dependence on hydrocarbon imports. Boosting recycling industries is also a good way of creating new jobs.

Sustainability. This is obviously connected to my second point on local supply chains. More broadly in the sustainability space, petrochemicals companies are going to face increasing carbon taxes and/or tariffs as environmental legislation gathers momentum, backed by strong public support.

Affordability. The income and wealth losses resulting from the pandemic have accelerated and amplified the push towards greater affordability, which was already underway as a result of ageing populations.

In my view, for reasons that go far beyond just a rise in China’s self-sufficiency, the petrochemicals industry needs a new business model. I believe that opportunities to make very good returns from this model will be at least as good as under the old model – probably better. But there is no time to waste in moving towards this new business model.