By John Richardson

IT HAS been an amazingly half a century of innovation for the petrochemicals industry. The light-weighting of automobiles, combined with booming demand for autos, has delivered many billions of dollars of value to companies.

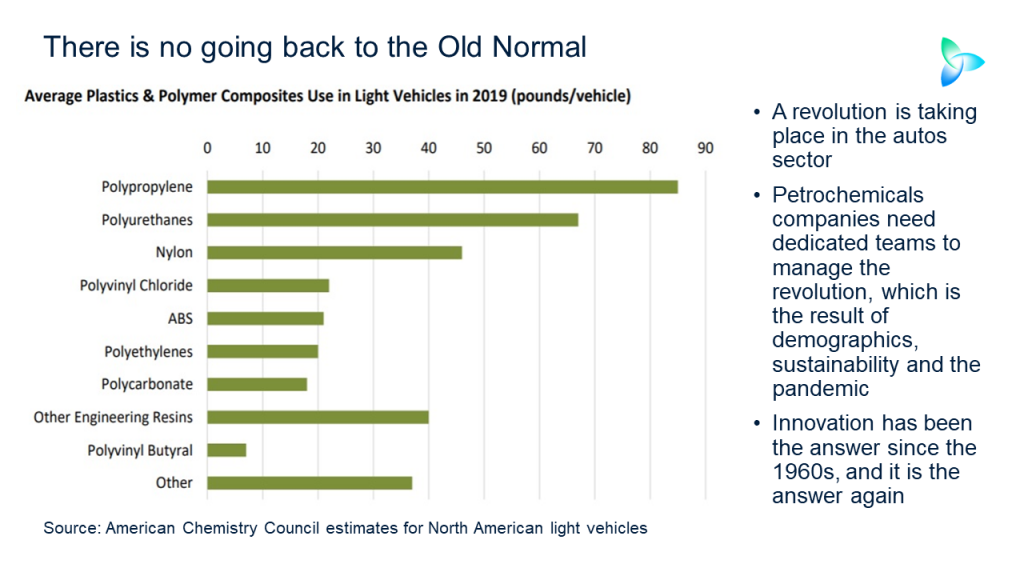

The latest figures from the American Chemistry Council, which only cover North America, give a pointer towards the global value gained by petrochemicals and polymers producers that serve the auto industry.

In 1960, the average weight of plastics and composites in each vehicle sold in North America was just 20lbs (90.7kg). Last year, the average had reached 362lb, or 164.2kg, as my very good colleague and friend, Nigel Davis, writes in another of his many excellent ICIS Insight articles.

The above chart shows the extent of the petrochemical industry’s exposure to the direction of the autos industry. As you can see, polypropylene is the most exposed, in terms of weight consumed in the average North America light vehicle, followed by polyurethanes.

Also consider demographic trends that boosted auto ownership in the West. As the Babyboomers entered the workforce from the 1970s onwards, this unprecedented in the number of working-age people led to a big rise in demand for private mobility.

Then came the rise in demand for individual car ownership in the developing world, first led by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan and more recently by China.

But we, quite literally, haven’t got a clue about the exact nature of what happens next because of the number of variables.

Using a famous phrase from a British quiz show, here is my starter for ten on just some of the variables.

The electrification of vehicles may lead to reduced pressure for further light-weighting. The point of light-weighting is fuel efficiency. However, as electric vehicles take over, the need to constantly improve the number of kilometres we get out of each litre of gasoline or diesel could disappear.

There are those who argue that electrification will never take off. I disagree. I also believe that the pace of electrification will be a lot quicker than conventional thinking suggests.

Or is this bunkum? Will reducing the weight of vehicles still be important in order to extend distances between recharging batteries? This could be very important as recharging infrastructure may be much less-than-optimal for a good many years. Or will improved battery technologies solve the problem of a lack of charging points?

China aims to boost its global standing

Electric vehicles contain fewer than 20 moving parts compared with as many as 2,000 moving components in gasoline and diesel vehicles. The far fewer number of moving parts electric vehicles could further damage petrochemicals demand.

We need to consider demographics in detail. When you retire, you are no longer travelling to work or taking the kids to and from school and football practice. The number of retirees is rapidly rising in Western societies as the societies in parallel suffer from a dearth of young people. Japan and South Korea have long been aged societies, ahead of the West. China is also heading in this direction.

The invention of social media and the rise of the Millennials appear to be other negative factors for autos demand. Why bother driving to your friend’s house when you can message them on Facebook? Why own a gasoline or diesel car when it is a bad thing for the environment? The Millennials, a global community that share values via their smartphones, are largely convinced that climate change is man-made.

China’s desire to boost innovation in renewable energy and electric vehicles, as it attempts to escape a middle-income trap resulting from its rapidly ageing population, is another critical factor. It must move up the manufacturing value chain to justify the higher wages caused by an ageing population. Beijing has chosen renewable energy and electric vehicles as two of the higher-value industries that can help China escape its middle-income trap.

We also need to consider the broad relevance of this week’s announcement by China that it plans to be carbon neutral by 2060, made at the virtual UN General Assembly in New York. China’s president, Xi Jinping, in making the announcement, promised a “green revolution”.

In my view, there are three drivers, if you can excuse the pun, behind this announcement:

- As the US rejects the global consensus that our activity is causing climate change, China sees an opportunity to boost its geopolitical standing.

- Further heavy state-led investment in electric vehicles can help China dominate the global electric vehicle industry in the way that it already dominates renewable energy. This will again help it escape its middle-income trap. China’s UN pledge points towards electric vehicles being a key part of its “green revolution”, as the transportation sector generates more greenhouses gases than any other sector or industry.

- The Chinese Communist Party has pledged to the Chinese people that it will deal with China’s chronic environmental crisis, and, as we know, gasoline and diesel cars do not just contribute to global warming; they also kill millions of people every year through air pollution.

The impact of the pandemic

One of the arguments that Dr Michal Meidan makes in this Oxford Institute for Energy Studies podcast is that e-bikes and e-scooters will take off in China because of the battle against air pollution and social changes resulting from the pandemic.

This looks set to be a global phenomenon. Will we ever work from the office as much as we did before the pandemic? I suspect not. So, own a car at all, even an electric one, when an e-scooter or e-bike is perfectly good enough for a quick trip down to the local shops? Or why not a pushbike

The rise of e-scooters, e-bikes and good old-fashioned pushbikes could blow a further hole in petrochemicals demand as, of course, by size these vehicles are a lot smaller. Or might the rapid rise in sales of these smaller-by-unit means of transport mean that, on a volume basis, demand improves?

Returning to the subject of automobiles, we need to evaluate autonomous driving. In a post-pandemic world where jobs are at a premium and creative destruction is rampant, the big-data and other technology solutions necessary to make autonomous vehicles work are a route to new employment. China might again seize the day here through its state-led investment model.

The Millennials will, I believe, see autonomous driving as the solution to their transportation needs because, as far fewer people would need to won cars, the industry will have a small environmental footprint. Lower car ownership would blow another hole in petrochemicals demand

Finally, the biggest influence of the pandemic on autos demand might well be lost wealth. In the developing world, excluding China, economic growth could be set back a generation, unless, and I am afraid this seems unlikely, the developed world provides more assistance.

The rate of economic recovery in the developed world will depend on the effectiveness of government policies, as governments will be the primary driver of economies for many years to come.

A critical factor for success is how governments manage the transition of stimulus from emergency support to creating new jobs in new industries. Can high levels of stimulus continue to be afforded? Not if inflation takes off. Pandemic-triggered problems with food distribution threaten a sharp rise in inflation and thus interest rates that would make public borrowing much more expensive.

Where is the feedstock going to come from?

Dr Meidan, in a September research paper for the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, wrote: “Over the past two decades, China’s oil consumption has grown by over 9m barrels per day (mb/d), according to BP, from 4.7 mb/d in 2000 to 14.1 mb/d in 2019. Yet over the next two decades, its oil use is expected to grow by 3–4 mb/d.” This sharp decline would be partly the result of the electrification of transport.

As electric vehicles take over, and as the social and economic consequences of the pandemic continue to play out, there are scenarios where oil demand fails to return to its pre-coronavirus levels. Two such scenarios are included in the latest BP Energy Review. As Nigel Davis again wrote:

“In two of the three BP scenarios (given the titles: Business as Usual, Rapid and net Zero), oil demand does not reach pre-coronavirus levels over the period to 2050.

“Changing consumer habits – including more home-working – will impact oil demand and the wider energy mix.

“Of greater importance is the negative impact of the coronavirus pandemic on developing and emerging economies that will be felt over many years. Oil will continue to be the major component of the energy mix, requiring significant investment of the next 10-15 years, but demand growth is under pressure.”

This raises the question of feedstock supply for the polymers and petrochemicals that go into autos. Will the availability of feedstocks, as refineries shut down, fall at a faster pace than the decline in demand from the autos sector, resulting in price spikes that constrain demand?

Or will it be the other way around? Will demand collapse faster than refineries shut down, leaving auto-related petrochemicals markets very long? Managing this volatility and uncertainty is going to be another major challenge.

All the above underlines my view that it is quite simply silly to estimate demand growth for any petrochemical into any end-use sector via multiples over GDP. This is way too simplistic and will never come close to giving us the answers we need, in my opinion.

We instead need rigorous and constantly adapted bottom-up analysis, from each end-use sector upwards. New bottom-up demand monitoring teams need to be set up by petrochemicals companies if they haven’t done so already.

The same applies to government policy. The extent to which, for example, China chooses to invest in electrification of transport will be a major shaper of future petrochemicals demand into autos. So will the success of developed world-governments in transitioning policies from emergency relief to new job creation. You need to set up another group of dedicated teams to monitor all the variables and uncertainties of government policy.

And finally, to finish where we started, it was, as I said, innovation that delivered such fantastic returns for petrochemical companies serving the auto space. We need to innovate again as the nature of private transportation undergoes nothing short of revolution. While the exact shape of the revolution is impossible to predict, the Old Normal will ever return.