By John Richardson

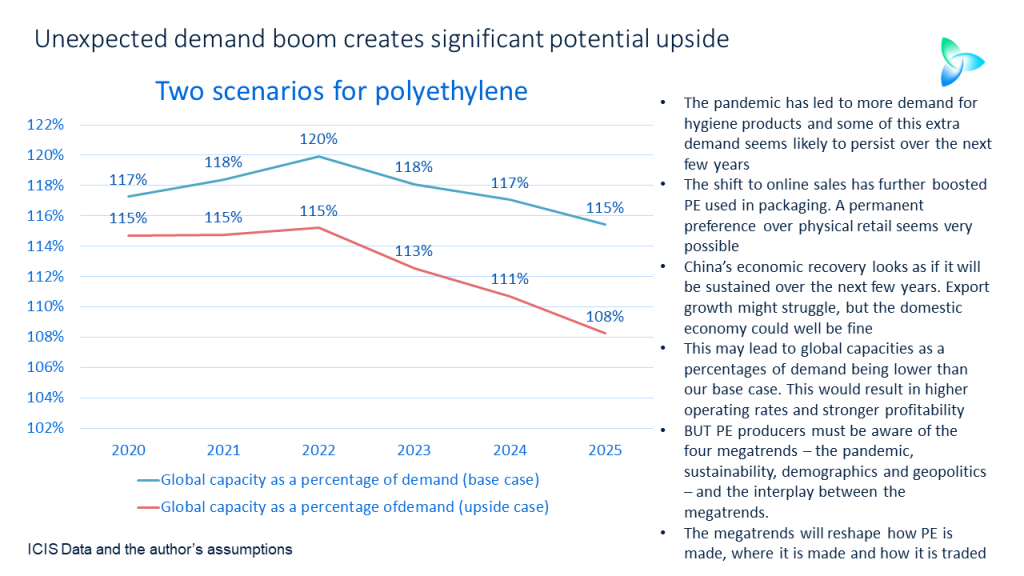

IT WASN’T supposed to be like this. We firstly had the unprecedented increases in global capacity that threatened a deep downcycle. Then we had the accepted wisdom, a wisdom I bought into, that the pandemic would dig a giant hole in polyethylene (PE) demand. As recently as March, few producers would have even in their wildest dreams contemplated a chart such as the one above.

Let me stress, though, that the above upside is my back-of-the-envelope estimate of what could happen in 2020-2025 versus our base case. My upside was produced through talking to contacts and a few hours of Excel work and should not be taken literally. It is for demonstration purposes only. For genuine scenario work on PE supply and demand, please contact me at john.richardson@icis.com and I will put you in touch with our outstanding ICIS analytics and consulting teams.

Whatever the actual numbers, it seems as if the PE market in 2020 has outperformed nearly all expectations. It is also possible that this strong performance will continue up until 2025. This would lead to demand much more easily absorbing the capacity surge, which was first led by the US and from next year will be led by China.

Why the market had performed so much better than many of us had expected seems to be for the following reasons in no order of importance:

- Increased hygiene needs related to the pandemic. Think of the extra demand for soaps, detergents, disinfectant, disinfectant wipes and PE packaging for face masks. The fantastic news is that we seem to have turned the corner on vaccines. But it seems reasonable to expect that even when mass and successful vaccination has taken place, some of this extra demand will endure because of the precautionary principle.

- Booming internet sales. Before the pandemic, online retailing was enjoying an extraordinary boom, especially in China. But for safety and convenience reasons (lots of shops have obviously been closed during lockdowns), the pandemic has led to a whole new level of growth. Take China as the prime example. This November’s annual Singles’ Day online shopping festival generated revenues of some $75bn versus last year’s $38bn for Chinese online giant Alibaba alone. As we get on top of the pandemic, some of the online demand might decline as we return to shops and restaurants. But do not underestimate the lure of convenience and new patterns of behaviour. Online food deliveries, through the rise of companies such as Uber Eats and Deliveroo, may have gained a permanent and much bigger share of the food market. Note that online sales have four times as many “touch points”, or stages of human handling, compared with conventional retailing. An item bought online is dropped by someone an average 17 times before it is delivered. This means a lot more plastic packaging than conventional retailing.

- Buying more supermarket food and reduced dining in restaurants. This appears to have increased the “surface area” of demand for polymers that go into packaging in general. “With more people eating at home rather than dining out at restaurants, overall food packaging film needs have risen as more food is being sold in individual packaging rather than bulk packaging,” writes my colleague Zachary Moore in this ICIS news article. But as we recover from the pandemic, this source of demand may decline.

- China’s rapid economic recovery. China had a plan and effectively implemented the plan, unlike some other countries that I best not mention. The plan meant it quickly brought the pandemic under control. Then it bought lots of cheap crude to improve the competitiveness of its refining and petrochemicals capacity and downstream to finished-goods manufacturing. It then added tax incentives for exporters, enabling China to increase its share of global exports as overseas lockdowns eased, with the exports wrapped in PE. China also makes most of the things we need for our new pandemic lifestyles that again come wrapped in PE – for example, the computers and office chairs we need to convert our homes into offices. Local retail sales have risen for the last three months in a row. This momentum should continue into next year, although the rise in lockdown measures during the northern hemisphere winter are a threat to China’s exports.

Now let me look at my above upside forecast in detail.

China and the developed world may outperform expectations

China’s apparent PE demand growth (the China Customs department demand for net imports plus local production) rose by 11% in January-October 2020 versus the same months last year. If you assume the same rate of increase for the full-year 2020, demand would be 1.6m tonnes bigger than our base case.

This would break down into much stronger-than-expected growth in high-density PE (HDPE) and linear low-density PE (LLDPE), but slightly-weaker-than-forecast growth in LDPE. LDPE demand is weaker because of its high cost relative to LLDPE, which can of course be used in many of the same end-use applications.

We had forecast an average 1% decline in US PE demand across the three grades in 2020 over last year. But the latest market intelligence, again in the article from my colleague Zachary Moore, suggests that growth could instead be a positive 2%.

The latest market intelligence for Europe suggests that demand might be flat this year or slightly stronger than in 2019, whereas our base case suggests a 2% decline. I have assumed a 1% increase for my upside.

In northeast Asia ex-China, we have again assumed a 2% decline. But I assume 1% growth. In the Asia & Pacific region, I have assumed the same decline in growth as our base case, which is minus 1% in 2020 over 2019.

For all the above countries and regions, my 2021-2025 upsides assume demand growth at one percentage point per year higher than our base case.

The end result is the upside of global capacity versus demand as percentages in 2020-2025 versus our base case in the above chart. My upside implies higher global operating rates and stronger profitability than under the base case. The base case foresees 2020-2025 capacity over demand as the highest percentage rates since 2000, whereas my upside assumes percentages below the historic trend.

If you want a breakdown grade by grade of how this upside was compiled, again contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.

And now look at the chart below which shows what my upside would mean in terms of cumulative demand between 2021 and 2025 for each of the grades of PE. The differences would be big.

BUT you must consider all four megatrends

The problem with my analysis to date is that it only considers one of today’s four megatrends, the pandemic. Missing is sustainability. Petrochemical companies need to make all four megatrends – the pandemic, sustainability, demographics and geopolitics – the cornerstones of their strategy.

If PE producers only report to investors booming single-use PE demand and the benefit to their short-term earnings, they will suffer reputational damage. Positive earnings reports need to be accompanied by a strong commitment to working with brand owners and internet sales providers to reduce the amount of single-use plastics in packaging.

In parallel, companies must work hard on developing chemical and mechanical recycled technologies. Refinery-based PE producers face the twin threats of losing their feedstock supply as refineries shut down and brand owners demanding that PE is made from recycled feedstocks.

Even in China, which is so, so important for global PE demand growth, we could eventually see the effective implementation of proposed heavy restrictions or even bans on single-use plastics.

There is also the broader issue of where virgin PE is made to service demand growth. As carbon tariffs and taxes are introduced it will become much harder to move PE long distance. This will lead to more regional markets as conventional cost curve analysis is upended.

Geopolitics will also make markets more regional as the US-China split continues. I believe we are heading for a bipolar world of two economic and geopolitical blocs, one led by the US and the other by China. China may end up only buying PE from within its trading bloc and China is by far the world’s biggest PE importer.

This would leave the US out in the cold and lead to more regional and less global investments to meet demand. It could become hard to justify building new PE plants in the US, but much easier to do so in China or most of the developing world (most of the developing world looks likely to end up inside the China bloc).

And remember, a reason for the China-US split is China’s ageing population and its need for greater access to higher value technologies, during a period when the US is restricting China’s access to the technologies. So here demographics, another of the megatrends, comes into play.

The rise of the Millennials, another demographic trend, helps explain strong public opinion in favour of action to deal with man-made climate change and the plastic waste crisis.

None of the above big picture issues will in my view significantly affect the quantities of PE demanded up until 2025. But they will affect how and where the PE is made and how it is traded.

These big issues may seem irrelevant to PE sales executives mainly focused on 12-month sales targets.

But boards of directors must be aware of the boiling frog analogy (as an animal lover, I hate this analogy, but unfortunately, I cannot think of a more appropriate analogy for the situation we are in).

As the metaphorical water of the interaction between the four megatrends gradually warms up, unless companies start to adapt their strategies now, they could in a few years’ time find that it is too late. The frog could have already boiled to death.