By John Richardson

CHINESE government statements have always been incredibly important for fathoming the country’s economic direction and this year will be no exception. We need to constantly parse the tone of statements to sense changes in direction.

“The current complex and severe international environment have added new uncertainties, the domestic economic recovery is not balanced,” said China’s Premier Li Keqiang to a forum of economists and entrepreneurs, according to this South China Morning Post (SCMP) article.

“[China will] strengthen market regulation of raw materials to ease the cost pressure of companies.”

China’s Financial Stability and Development Commission issued a rare warning last week about the rise in commodity prices. The March official Producer Price Index was at 4.4%, its highest level since July 2018.

Higher oil, petrochemicals and other commodity prices could feed through into global inflation via China’s finished-goods exports, thus dampening demand for the exports.

Higher inflation may, of course, also adversely affect the local economy.

Then there is the debt issue which was on the backburner during the US/China trade war and during the 2020 pandemic. Bloomberg reported that last year Chinese banks provided a record yuan (CNY) 9.6tr ($3tr) of credit, with about a fifth directed to inclusive financing such as small business loans.

The same Bloomberg article said that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank, had asked lenders to keep new credit in 2021 at about the same level as last year.

The PBOC is engaged in a campaign to stamp out illegal speculation, according to an official statement. The statement includes the following:

“Operating loans have played an active role in meeting the temporary revolving capital needs of small and micro enterprises and improving their continuous operation capabilities.

“However, in some hot cities where housing prices are expected to rise strongly and the atmosphere of speculation is strong, fraudulent bank operating loans are actually used to purchase houses, and some even involve organised illegal activities.”

Paul Hodges, one of the independent thinkers on China whose views I highly value – and who has very often been right – has looked at the latest Chinese lending data. He has reached the following conclusions:

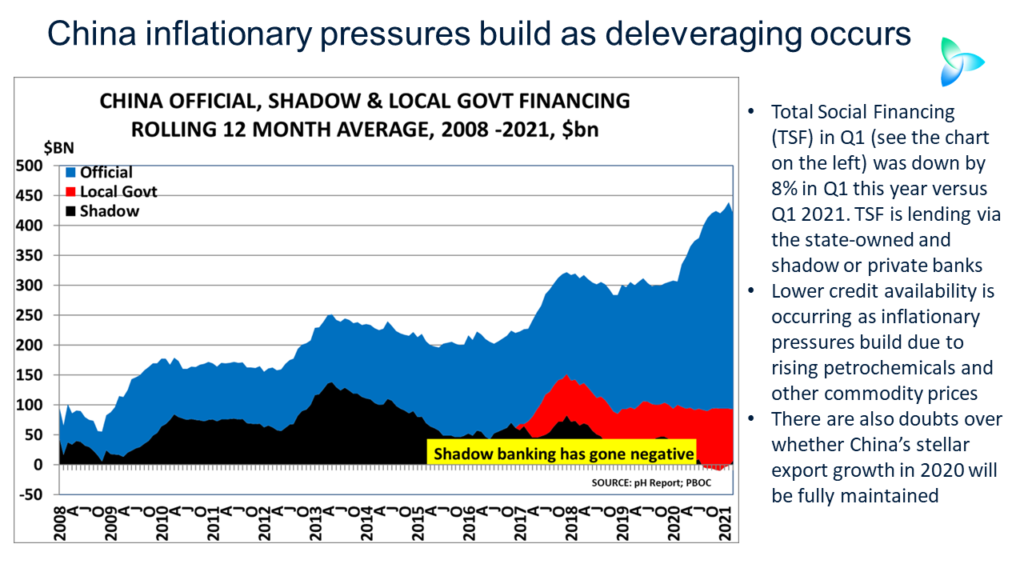

- There are signs the government is starting to significantly reduce credit availability. This is evident from the slide at the beginning of this blog post. What it shows it China’s Total Social Financing, which is lending from the state-owned banks and the private or shadow lenders. Q1 2021 lending was down by 8% year-on-year.

- This is particularly bad news for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which employ some 200m people and comprise many petrochemicals end-users. They are heavily dependent on government tax exemptions, rent cuts and loans via the shadow-banking sector.

- As the chart illustrates, shadow-bank lending was steadily reduced in 2020 with the process accelerating in Q1.

- But the big state-owned enterprises (SOEs) might be fine as they source most of their financing from the state-owned banks. The state-owned banks have assumed a much bigger role in lending over the past 15 months.

The above chart, courtesy of Paul, shows an 18% fall in Total Social Financing (TSF) in Q1 this year versus Q 2020, a clear sign that delevragin

Reduced credit might help explain why the China Caixin/Markit Manufacturing Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) for March was at its lowest for nearly a year at 50.6. Another factor was likely the rise in raw-material costs. The Caixin/Markit PMI mainly focuses on the SMEs.

This contrasted with the official March PMI which was at 51.9 compared with February’s 50.6. The official PMI mainly surveys the SOEs.

I have long documented China’s rising debt challenges, right back to when debt really started to take off immediately after the Global Financial Crisis. Since then, Beijing has blown hot and cold on reducing leverage.

A further sign that the temperature has once again been turned up on debt comes from another SCMP article. The article said that there had been a shift away from China’s investment-led growth model, based on a circular from China’s State Council.

“We must properly handle existing [debt] piles … And we must not have new projects that could incur new implicit liabilities,” the State Council said, according to the SCMP. The State Council is China’s chief administrative body.

The central government had reduced this year’s local government special-purpose bond issuance quota to Yuan3.65tr ($557bn) from Yuan3.75tr last year, wrote the newspaper.

Further risks to Chinese exports that need to be assessed

Booming Chinese finished-goods exports in 2020 greatly benefited both local and global petrochemicals demand. It was the “China in, China out” story – a surge in petrochemicals imports that were re-exported as many the things that met our pandemic needs.

What happens next to exports depends not just on whether today’s raw-material cost inflation continues.

If the developed world brings the pandemic fully under control in 2021, there will be a cycle out of demand for the goods and services we needed during the pandemic and back into Old World spending.

This could mean less demand for laptops, computer monitors and washing machines etc. and more demand for the goods and services associated with travel and working from the office. Would such a cycle be positive or negative for Chinese exports?

It seems reasonable to assume that, regardless of the progress on bringing the pandemic under control, strong demand for personal protective equipment and hygiene products is here to stay for a long time. This would mean continued strong demand in China for non-woven grades of polypropylene (PP) to make face masks for export.

We are in an era when governments in the developed world have adopted a much more influential role in the direction of economies.

We need to assess the scale and effectiveness of stimulus in the US versus the EU. These assessments must also factor in the abilities and willingness of different age and income groups to spend government handouts.

To what extent will government spending on infrastructure boost economies? Could runaway inflation bring the party to a halt? I think not, but this also needs to be considered. When the models generate results, we then need to assess the implications for China’s petrochemicals demand.

What this could mean for petrochemicals

China’s polyethylene (PE) demand might to some extent be immune from macroeconomic problems because of the growth of packaging demand. This includes resilient local demand for PE in hygiene end-use applications.

Even though China has the pandemic well under control, the precautionary factor guarantees continued strong demand for hygiene products such as hand sanitisers. The bottles are made from high-density PE (HDPE) blow moulding grades.

There is also likely to be continued strong growth in internet sales. Internet sales require lots and lots of PE packaging.

Still, though, 10-15% of PE imports are thought to be re-exported as either packaging for finished goods or as finished good themselves. Less demand for shrink wrap for exported Chinese washing machines and laptops could be an issue.

So might be Beijing’s clearly stated intention to slow infrastructure work, reducing demand for HDPE pipes.

Some 20-30% of imported PP is understood to be re-exported as finished goods. But both imported and locally produced non-woven grades will likely see continued strong support from face- mask demand, regardless of the macroeconomic background.

Also, though, think of the other grades of PP that go into exported white goods. Consider the PP that goes into the auto sector, which is suffering the most from the semiconductor shortage.

Between 30-40% of the styrene monomer (SM) China imports is said to be re-exported as finished goods that contain the polymers made from SM. SM is therefore the most exposed to any export slowdown.

PE, PP and SM would also suffer from a credit contraction. The super-hot property sector is, for example, an important end-use market and a credit contraction would reduce some of the real-estate heat.

PE, PP and SM net import data for January-February 2021 has already pointed to a sharp slowdown in apparent demand versus November-December 2020, as I discussed earlier on the blog. This is the only valid comparison as in February-January 2020, the pandemic was at its height in China. This is making all year-on-year comparisons look good.

But of course, even though I “chanced my arm” with some projections for China’s full-year 2021 PE and PP demand based on this year’s January-February data, it is far too early to reach any firm conclusions. These forecasts were instead aimed at getting your attention.

Why I was eager to get your attention is my argument that you need a rigorous scenario-based approach to understand what is happening out there. This has long been the case, of course, but a scenario-based approach is even more important now because of all of today’s complexities.

Please, please be careful out there. You must prepare for a wide range of outcomes while not listening to anyone who tells you, “don’t worry, it is all very straightforward.” It is clearly not straightforward.