By John Richardson

MIDDLE EAST, southeast Asian (SEA) and northeast Asia (NEA) ex-China petrochemicals producers need to transform themselves because of China’s rising self-sufficiency.

In polypropylene, styrene monomer (SM), ethylene glycols, paraxylene and methanol, China has the potential to by itself reach complete self-sufficiency over the next two-to-five years from its position today of being by far the world’s biggest importer.

In high-density polyethylene and low-density polyethylene, China doesn’t appear to have the capability of reaching anything close to self-sufficiency by itself anytime soon. But it might be able to reach “virtual self-sufficiency” in partnership with Iran, following last month’s signing of a major economic and geopolitical deal by the two countries.

The deal could see as much as $280bn of Chinese investment in Iranian oil, gas and petrochemicals out of total Chinese investment in Iran of $400bn.

Whatever the outcomes of China’s push towards greater self-sufficiency, there is one thing I believe we can be certain of: China will obtain petrochemical imports at a cost that will support its future economic development.

The reason is that China can at any time decide to accelerate or decelerate its push to greater self-sufficiency because it has ample capital, low construction costs compared with other regions and adequate access to technologies in commodity petrochemicals. It thus holds a very strong bargaining chip.

Scenarios for China SM imports and exports in 2020-2021

Let me stress here, before I look at the data on styrene monomer (SM), that many of the companies in the Middle East, SEA and NEA ex-China are well down the path of diversification away from a heavy reliance on exports to China.

But for any companies that might be in the early stages of a strategic shift away from a reliance on exports to China, I hope my thoughts later in this post help with internal discussions.

Now let us take a deep dive into the ICIS Supply & Demand data on SM. Let’s at first look at scenarios for imports and exports in 2021-2031:

- Even our base case assumes a collapse in China’s SM imports over the next 10 years. Under the base case, we see imports in 2021 falling to 2.2m tonnes – 22% lower than last year. Imports then steadily decline to just 356,000 tonnes in 2031. This scenario assumes an average annual operating rate of 60% and average annual demand growth of 3%. We also assume that none of the 6.7m tonnes/year of capacity listed as unconfirmed goes ahead. These are new plants lacking final approval, financing, feedstocks and technology etc.

- My downside also assumes that no unconfirmed capacity happens. I also assume growth is at the same annual average and follows the same yearly patterns as in our base case. The only change I have made is to operating rates. I have raised operating rates each year until they reach a 2021-2031 average of 65%. Imports fall to 1.6m tonnes in 2021 – 45% lower than in 2020. China is exporting 65,000 tonnes in 2024 as imports vanish. Imports peak at 598,000 tonnes in 2028 before China returns to very small import positions in 2029-2031.

It would have been easy to have raised operating rates even higher to the point where China became a big exporter. But where would China send these volumes given that in 2020, we estimate that China accounted for 69% of total global net imports? (this was among the countries and regions that imported more than they exported).

The impact on China’s top six SM trading partners

The above chart shows the impact on China’s top six SM trading partners, based on China’s 2020 import data. Saudi Arabia was No1 at 35% of total Chinese imports followed by Kuwait at 13.4%, Japan at 13%, Taiwan at 12.6%, Singapore at 8.4% and South Korea at 6.5%.

Assuming the trading partners keep the same market shares in 2021-2024 that they achieved last year, even our base case sees imports substantially down in 2021-2024 from these six countries. My downside sees imports disappearing entirely in 2024.

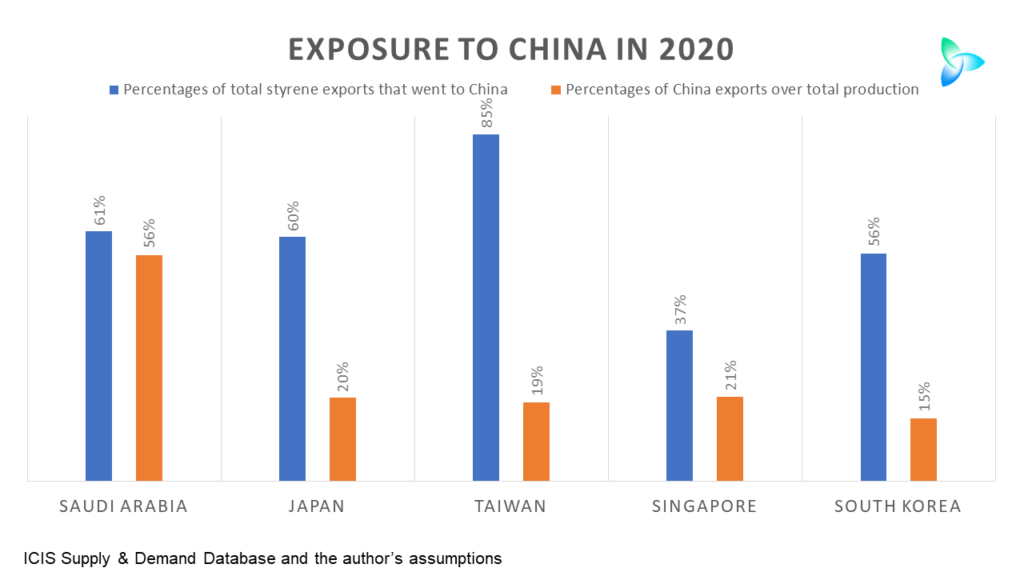

Now let us consider the third chart below.

Here, I took the exports to China that five of the six countries reported for 2020 versus their total exports (there was no data available for Kuwait). As you can see, the most exposed in this respect is Taiwan as 85% of its total exports went to China.

But what could matter more is exports to China as percentages of our estimates of total production. On this measure, 56% of Saudi Arabian production in 2020 represented exports to China. This was followed by 21% for Singapore and 20% in the case of Japan.

Sustainability as a way forward

Let me again stress that many of the companies in the three regions are already well down the path of compensating for the potential loss of exports to China.

Aside from diversification downstream, the other approach has been to build capacity in China itself. Saudi Arabia has major investments already on the ground in China and is planning new complexes in several of the petrochemicals and polymers at risk.

I also see sustainability as a key area for future growth in the Middle East, SEA and NEA ex-China. Again, initiatives are already underway in the areas I discuss below. But a lot more value can be unlocked as companies increase their focus on sustainability.

I see the next wave of global growth as coming from technologies that enable electric vehicles, smart grids and the internet of things.

Apart from the material science opportunities, developments in global trading and credit schemes will provide another revenue source.

So will more carbon efficient refinery and petrochemicals complexes that make use of emerging technologies such as green and blue hydrogen and electric cracker furnaces. Technologies can be developed and kept inhouse or licensed.

For economic and logistics reasons, I believe the jury is still out on whether we will see a big scale plastic and/or chemicals recycling industry. Nevertheless, this should be another area of cautious and pragmatic focus.

But where I see a definite opportunity is taking the lead on solving the world’s plastic rubbish crisis.

A 2018 study found that 90% of the plastic rubbish in the world’s oceans came from just 10 rivers, eight of which are in Asia with the other two in Africa. An estimated 2bn of the world’s population lack access to modern rubbish collection systems, so they few options other than to leave plastic in the open environment.

I see every chance that this crisis will lead to something akin to the Paris Agreement on climate change – an international deal designed to reduce the leakage of plastic waste into the oceans. As we see global carbon taxes and credit schemes introduced, the same could happen in plastic waste as countries attempt to adhere to the new global plastic agreement.

Petrochemicals companies that take the lead in setting up waste collection systems in the developing world may end up with a “cost curve” advantage other the competitors. The winners will be able to either avoid plastic taxes or gain credits that they can then trade.

From petrochemicals inflation to deflation

The above charts are, as always, for demonstration purposes only. They do not represent anything close to the in-depth scenario work that can be provided by our analytics and consulting teams. And, of course, as soon as the ink is dry on the charts, events will have moved on.

But I believe whatever the statistical outcomes, which you must constantly monitor using our data, the essential outcome is the same: we will move from today’s world of petrochemicals inflation to one of deflation because of decisions taken by China.

The new opportunities for growth, though, are big for companies with the right focus.