By John Richardson

I MADE THE argument last Thursday that until or unless the world is fully vaccinated against the pandemic, container freight chaos would continue because of further waves of port restrictions such as the ones taking place at ports in Guangdong province.

My argument is that we must raise vaccination rates in the developing world to acceptable levels from today’s paltry and wholly inadequate levels. Otherwise, time and again we are going to see more outbreaks such as the one in Guangdong which is the result of the Indian Delta strain of the virus.

The longer the developing world remains inadequately vaccinated the more likely it is that new vaccine-resistant strains of coronavirus will spread from poorer to richer countries because we live in a highly interconnected world.

The post was written as a call for common economic sense – and because this is morally the right thing to do. It is shockingly bad that the G7 meeting earlier this month in Cornwall, the UK, concluded with an agreement to supply only 1bn doses to poorer countries when the World Health Organisation says 11bn doses are need. Come on, wake up politicians and do the right thing!

But in this ever-more complex world, what about the likelihood that all of us are going to need to “top-up” vaccinations every year as the coronavirus continues to mutate, just like the flu jab?

This will require adequate supply of updated vaccines to the developing world every year. Also needed are investments in enough new roads and better healthcare systems in the poorer countries to ensure vaccination rates remain high-enough over the long term. Access to cheaper finance for developing world governments is also essential

And click here to see another excellent chart from Our World in Data. No less than 28% of people in the US and 30% in France were unwilling to receive vaccines as of 31 May. Now I could get into a lot of trouble here, so I will steer clear of the “anti-vaxxers” debate. But suffice to say, these high numbers are a threat to the world reaching herd immunity.

Populist politics might also be getting in the way of us fully emerging from the pandemic. I am again going to tread very carefully by allowing you to furnish yourselves with the details.

There are other non-vaccine related complications that we need to consider such as the pandemic-related boom in demand for finished goods, leading to shippers employing more and larger container vessels.

“Ocean carriers have been deploying more and larger vessels to catch up which is creating chaos at the ports,” said Rich Thompson, International Director of Supply Chain & Logistics Solutions at consultancy JLL in a 4 May article in Supply Chain Management Review.

Swings in demand were another problem identified by Thompson in a research paper he co-authored – The Shipping Crisis.

What polymer producers should do

One of the many variables the container industry is struggling to manage is the extent to which government stimulus will boost demand.

This circles back to the kind of analysis recommended by The Economist in a March article. The magazine suggested it was necessary to consider demographic profiles and income levels to assess the impact of stimulus on consumer behaviour.

In Q4 last year, Chinese manufacturing output reached its highest level in five years. But there remained a backlog of orders because US manufacturing capacity utilisation was still not back at pre-pandemic levels, wrote Logistics Management in a 2 June article. This was the result of difficulties in attracting US workers and shortages of imported components.

The slowdown in the growth of Chinese exports in early 2021 versus late 2020 – the result of both the container freight and semiconductor shortages – has added to the backlog in US orders.

The Guangdong port disruptions is making the slowdown worse as 24% of all Chinese exports come from southern China. I am hearing reports of factories having to shut down because of the logistics disruptions in southern China.

I believe we must be prepared to manage a very different container freight market over the long term. Here are some suggestions about what to do:

- Keep a razor-like focus on fluctuating regional price differentials and the availability of container freight space to take advantage of these differentials. A good example of how this can provide polymer producers with short-term wins is in polypropylene (PP) where in January-April Chinese producers increased their exports by 344% over the last four months of 2020. Destinations included Vietnam, Indonesia. Turkey and even Peru.

- Stay much closer to container-freight companies than was the case in the past. Connected to this is the requirement for more detailed and frequent monitoring of shifts in freight rates. Better forecasting of freight rates is also essential.

- Consider the extent to which price fluctuations are the result of changes in freight costs. We are working at ICIS to provide you with more visibility on the impact of freight rates on polymer prices.

Why this analysis is well worth the investment

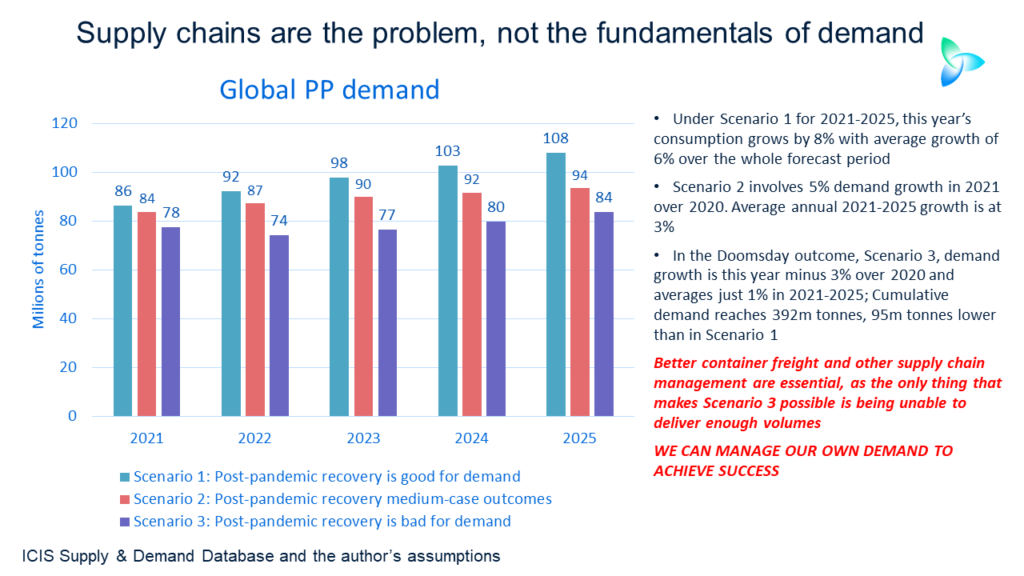

Spending more time and money on container-freight visibility will reap rich rewards if either Scenarios 1 or 2 in the chart at the beginning of this blog come true.

I don’t see any problem with the fundamentals of polymers demand as I don’t buy the notion that even if we see another global recession, consumption will see a steep decline. This is because of the big changes in end-use markets that I have been detailing since mid-2020, including much greater hygiene needs and the rise in internet sales.

Let us flip the coin and assume we see a continued strong economic recovery rather than a new recession.

I also don’t buy the argument that there would be a circle out of demand for some goods and into more services as people return to travel and dining in restaurants, reducing polymers demand and the pressure on container space.

The reason is again permanent changes in end-use markets. The rise in packaging demand is, for example, huge in sectors such as internet-ordered takeaway food and groceries.

It is thus essential that you better manage your supply chain to maximise your volumes in this strong demand environment.

An example of how strong demand could be is in the chart at the beginning of this blog post. Here again are three of my scenarios that are for demonstration purposes only. Please contact me at john.richardson@icis.com to connect with our analysts and consultants for complete scenario work.

I believe that in 2020 over 2019, global PP demand grew by a very healthy 5% over the previous year to slightly below 80m tonnes.

Under Scenario 1 for 2021-2025, I see this year’s consumption growing by 8% with average growth of 6% over the whole forecast period. Cumulative consumption would reach 487m tonnes.

Scenario 2 involves 5% demand growth in 2021 over 2020. Average annual 2021-2025 growth is at 3% with cumulative demand at 446m tonnes – 41m tonnes lower than in Scenario 1.

In the Doomsday outcome, Scenario 3, demand growth is minus 3% this year over 2020 and averages just 1% in 2021-2025. Cumulative demand reaches 392m tonnes, 95m tonnes lower than in Scenario 1.

For Doomsday to happen, container freight and other supply-chain problems -such as semiconductor, labour and lumber shortages – would need to be so severe that sufficient PP would not be able to be supplied to meet demand.

These problems could be compounded by continued shortages of PP supply due to, say, severe hurricanes during this year’s US Hurricane Season, more power outages in the US at the height of the summer and further force majeures in other countries.

Here is the thing: the better that we as an industry manage supply chains in general, the less likely it is that this worst-case outcome will happen. In other words, we can shape our own demand.

It will be critical in PP for producers to maximise shipments to the markets where it is needed because of rising Chinese self-sufficiency. China’s PP Imports could very easily fall to around 4m tonnes this year from 6.6m tonnes in 2020. They may be as low as 1.3m tonnes in 2025.

You do not want to find as China’s imports fall you are unable to ship to the other big import markets such as Europe, Turkey, southeast Asia, Africa and South & Central America

I know I have been labouring the point, but it needs to be laboured. I am going to labour the point again: what is there not to like about deeper and more sophisticated supply chain management?