By John Richardson

SEE THE END section of this blog post for a dystopian version of our environmental future. In a follow-up post – which I will publish on Thursday, 1 July – I will offer some suggestions about how we can avoid an outcome that nobody of course wants.

Both posts are meant to be provocative, challenging and controversial because only through debate, and sometimes outright argument, will we get to the answers.

If you disagree after either or both posts have been published, great, that would be good. In fact, I would love to hear from you whatever your views at john.richardson@icis.com. The petrochemicals industry can do this; we can fix this if we create the right forums for ideas and then solutions.

Let me provide the background first. Let me start by examining developments in the refinery industry and the implications for petrochemicals as important background. Then I will look at a sample of ICIS petrochemicals demand growth forecasts for 2020-2040. I will conclude by providing the bleakest of bleak outcomes for the world in 2025

Maybe this outcome can already be ruled out because of the progress made in solving our environmental challenges. If so, I would again be delighted to hear from you with supporting data, as I have yet to be convinced by the numbers that I can find.

I worry that the data are building up in favour of the grim outlook in the post’s final section, which I first presented in a blog post earlier this month.

Data relating to the pattern of future refinery investments further supports this outcome as does The Economist’s estimate that only 10% of the energy transition is complete. A further $35tr of investment needs to be attracted before 2030 if we are to stay on the course of net zero emissions, adds the magazine.

Middle East and Asia mega-refineries and the pressure on the West

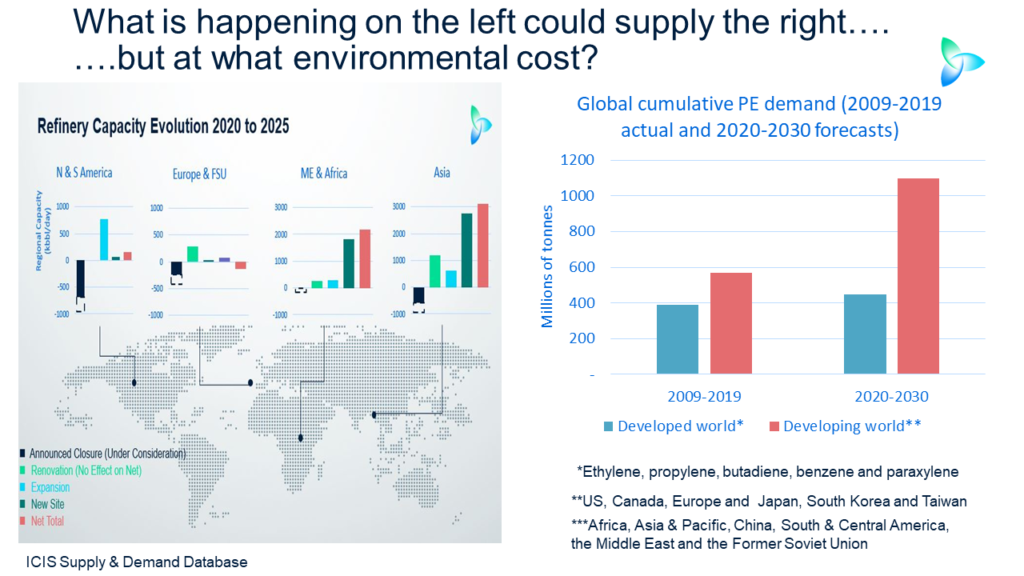

Look at the above slide at the chart on the left from my ICIS refining and energy consulting colleagues Michael Connolly and Ajay Parmar.

The chart is telling us this: from 2021-2025, eight new mega-refineries are due to come on stream which, together with major expansions at existing sites in India and China, will add 4.2m bbl/day to net global capacity. This extra capacity includes forecast refinery closures.

“These new, efficient capacities in the Middle East and Asia will put pressure on older refineries in places like Europe and the US where we expect to see more closures as the new refineries come onstream,” said Michael in this free-to-view ICIS news article by another of my ICIS colleagues, Will Beacham.

Mega-refineries have the capacity to process at least 200,000 bbl/day of crude oil compared with a global average of 122,000 bbl/day.

The pandemic has further undermined the viability of sub-world-scale refineries. In Europe, there have been around 500,000 bbl/day of permanent refinery closures over the past 12 months because of the collapse of transportation fuels demand. At least five more refineries in Europe are still idled and face an uncertain future.

Europe lost 1.5m bbl/day of production in 2020, but only one third of that is forecast to be recovered by 2023. From then on, a structural decline is forecast.

Developed-world energy majors also face rising pressure from investors and environmental activists to aggressively reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Shell has been ordered by a Dutch court to accelerate its emissions reductions following a case brought by environmentalists. Three environmental active investors have won places on the ExxonMobil board. Chevron investors voted for deeper and more rapid cuts in emissions than the company had proposed.

There are lot of plans for converting refineries in Europe to biofuels production. There are also substantial plans for building mechanical and chemicals recycling facilities to try and make up for petrochemicals feedstock shortfalls.

But even with substantial investments in recycling, it seems possible that European petrochemicals producers will struggle to source feedstock as refinery closures gather pace. Naphtha might have to be imported, incurring higher logistics costs and competition from other regions.

It is not just in Europe and the US where refineries are under pressure. Shutdowns have also taken place in Asia and Australia.

But the mega-refineries in the Middle East and Asia, especially in China, have placed the regions in very strong competitive positions, I’ve been told. The refineries are gaining good margins from transportation fuels and petrochemical feedstocks, enabling them to meet booming developing world demand at affordable costs.

New refineries are heavily focused on providing petrochemical feedstocks – up to a maximum of some 45% of any refinery’s output, I have again been told.

China has seen big wave of new refineries, several privately owned, that are heavily focused on providing petrochemicals feedstocks.

Now let us look at the chart on the left to discuss the details of booming petrochemicals demand in the developing world and how this links to the ICIS refining numbers

Everyone has a right to the things that some of us already have

What you can see in the chart is historic polyethylene (PE) demand growth in 2009-2019.

Cumulative demand in the developed world totalled 390m to tonnes in 2009-2019 The developed world consists of Australia, Canada, Europe, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and the US.

The developing world comprises Africa – Asia & Pacific minus the developed regions listed above – China, South & Central America, the Middle East and the Former Soviet Union. Developing world demand reached 448mtonnes in 1999-2019.

Consider the expected turnaround in 2020-2030 Developed world demand is expected to see healthy growth of 15% to 579m tonnes. But consumption in the developing world is forecast to soar t0 1.bn tonnes – an increase of 92%.

Similar patterns apply to all other petrochemicals and polymers.

“Well, people just need to consume less if we are going to deal with our environmental challenges,” I have heard some people say.

If this is the message that is consistently transmitted from richer to poorer countries, the response of the poorer countries will rightly be, “We are entitled to things that you have. Don’t be so hypocritical and patronising”.

Think of all the life-extending and life-improving manufactured goods and services that our industry provides the raw materials for.

Look again at these demand growth numbers and think of this growth in the developing world as an incredibly good thing. The consumption outcome would represent great economic and societal progress as we solve the problems of lack of sufficient potable water, fresh food and modern sanitation etc. Millions more people would escape extreme poverty.

The products that meet these basic needs include medical devices, medical packaging, personal protective equipment to deal with the pandemic, plastic films that preserve food and sewerage, potable water and irrigation pipes. The products are all made from petrochemicals.

The demand growth also implies that many millions more people will climb up the income ladder well beyond extreme poverty and into middle-income status. This is will make scooters and eventually motor cars affordable for the first time, along with refrigerators, washing machines, basic computers and mobile phones.

The World in 2025: Environmental Disaster approaches

Developed-world oil, gas, refining and petrochemicals companies confront increasing investor and legislative pressure to cut their carbon emissions. This is one reason why developed world majors have been forced to freeze new investments in oil and gas exploration through to petrochemicals.

Another reason is the loss of petrochemicals feedstock supply because the fall in demand for transportation fuels due to electrification has led to many refinery closures in Europe and the US.

Another wave of new mega-refineries in the Middle East and Asia had added to the momentum behind refinery closures in the West. The developed world majors have been increasingly squeezed out of gasoline, diesel and other transportation fuels markets.

Meanwhile, ambitious plans to scale up production of feedstock from mechanical and chemicals recycling facilities have been thwarted by insufficient investment and technological and logistics barriers.

In existing refining-to-petrochemical complexes, the developed-world majors have employed greenhouse gas-reducing technologies such as electric furnaces and green and blue hydrogen.

This has given them a competitive edge in the EU market. This is the result of carbon border adjustment mechanisms levied on imports of petrochemicals down to finished goods from countries the EU considers behind the curve in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

While the US hasn’t gone as far as carbon border adjustment mechanisms, local energy-to-petrochemicals face much more limited sources of financing for non-sustainable investments. They too have had to invest heavily in emissions-mitigating technologies at their existing plants.

This lack of financing has also stymied further expansion of US ethane and LPG-based petrochemicals capacity. Environmental restrictions on expansions of shale oil and gas production have further limited the producers’ flexibility.

But developing world companies have been able to build lots more crackers, reformers and downstream plants in the old-fashioned ways with no restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions. These are being fed by competitively priced feedstocks from the region’s mega-refineries, and from the region’s natural gas industry.

Building new old-style petrochemicals plants in the developing world has served three purposes:

- Meeting the huge demand growth that you can see in the above chart.

- After the economic devastation caused by the pandemic, the developing world was in desperate need of new industrial projects for the sake of the economic multiplier effect.

- As the developed world has pushed ahead with electrifying transportation, this has created a problem for the National Oil Companies because of the fall in oil demand. Petrochemicals are partially helping to compensate for this loss of demand.

And because oil is so cheap – and because resource-dependent economies need to find a home for their oil – electrification of transport is largely a phenomenon confined to the richer countries.

Anyway, even if the developing world had wanted to push ahead with electrification, it wouldn’t have been able to do so because it didn’t have sufficient funds for the huge investments in new recharging infrastructure.

Sadly, also, not enough help has come from the developed world to provide developing countries with the funding and technologies they need to build adequate plastic rubbish collection and processing systems.

The reason is too many people in the rich world have stuck to the mistaken belief that recycling is the only answer. But the still widely unrecognised root cause of the plastic waste crisis is that 3bn people lack adequate rubbish collection and processing systems. Most of these people live in the developing world.

Levels of plastic waste in the oceans continue to rise. A 2016 warning by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, that there would be more plastic in the oceans than fish by 2050, could come true by as early as 2040.

We have little chance of fulfilling the objectives of the 2015 Paris Agreement as our environment becomes more and more stressed.

In mid-2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produced a landmark report which warned: “Life on Earth can recover from a drastic climate shift by evolving into new species and creating new ecosystems … humans cannot”.

The IPCC’s warnings of irreversible tipping points – such as melting permafrost that releases methane – seem likely to come through. The number of severe heatwaves, fires, floods droughts and hurricanes has increased.

How do we stop this from happening? This will be the theme of my 1 July blog post.