By John Richardson

NOBODY SHOULD be surprised that the developing world has fallen behind in the battle to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as the region is a long way from recovering from the pandemic.

Evidence to this effect emerged last week in comments made by Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA).

“In many emerging and developing economies, emissions are heading upwards while clean energy investments are faltering, creating a dangerous fault line in global efforts to reach climate and sustainable energy goals,” said Birol.

At the current rate, carbon dioxide emissions from developing countries largely in Asia, Africa and Latin America are set to increase by 5bn tonnes/year over the next two decades, according to the IEA, as access to power increases.

At present, around 785m people worldwide have no access to electricity. There are also 2.6bn people without access to clean cooking options.

Vaccination rates in the developing world are also only a tiny fraction of those in rich countries, as I discussed last Thursday.

Take Africa is an example where less than 2% of people have received their first jab compared with 75% in the UK.

Last week’s G7 meeting in Cornwall, the UK, offered to provide 1bn vaccines to the developing world. But the World Health Organisation (WHO) said that 11bn vaccines were needed.

The WHO has called for 70% of the global population to be vaccinated by time of the G7’s next summit in Germany next year.

But the anti-poverty advocacy group One said the 1bn vaccines would only provide enough doses to vaccinate around 200m people by the end of the year – 10.3% of the population in low and medium income countries by the time of the next G7.

Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown said that the G7 had demonstrated “unforgivable moral failure when Covid is destroying lives at the rate of one-third of a million every month”.

The developing world needs cheaper lending

Even if enough vaccines are eventually delivered to developing countries, along with funding for distribution and delivery, support must go much further if we are going to make progress on reducing greenhouse gas emissions – and on the other big environmental challenge humanity faces. This is the plastic waste crisis.

“There is no shortage of money worldwide, but it is not finding its way to the countries, sectors and projects where it is most needed,” Birol added.

“Governments need to give international public finance institutions a strong strategic mandate to finance clean energy transitions in the developing world.”

Another aspect of the developing world’s financing challenges was also a theme of my blog post last Thursday.

The developing world must be given the ability to spend more money on monetary and fiscal pandemic-relief programmes, including investments in green energy. Right now, the region is hamstrung by high financing costs.

Monetary spending by high-income countries has averaged 15% of GDP versus just 3% in low-income countries since the pandemic began.

The reason is that while the cost of financing has declined below its long-term average in the developed world, it has increased in the developing world. Financing costs have diverged because of the different pace of vaccination programmes.

We must also consider what would happen if the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates in response to global inflationary pressures. This would make financing even harder for the developing world as the US dollar strengthened. A stronger dollar would raise dollar-denominated debt servicing costs.

More infrastructure money is also needed

Bridges, roads, ports, electricity supply, education and healthcare remain inadequate across a large swathe of the developing world minus of course China.

China might end up supplying most of the above through its Belt & Road Initiative. But while this could lay a firmer foundation for healthy economic growth, to what extent might coal play a part in providing new electricity supply, given that China has big coal reserves?

Here is a more positive outcome: China decides to lead the way globally in developing and exporting green technologies. This would fit with its desire for more geopolitical influence.

China must also escape its middle-income trap and a way of doing so is shifting into higher-value manufacturing and services. Green technologies fit the bill.

But will China win access to all the technologies it needs to make the green transition? Its clash with the US threatens to reduce its access to all types of higher-value technologies – although it is spending billions of dollars on local R&D.

China had more flexible planning rules than Europe, Martin Brudermüller, CEO of BASF, told the Financial Times. This meant Europe was at risk of falling behind in developing renewables, he added.

Will China, though, be prepared to transfer cutting-edge green technologies at affordable costs to the developing world? Or will the focus instead be on exporting old-world technologies such as coal-fired power plants?

In the end I believe that this circles back to the ability of regions such as Asia and Pacific, Africa and South & Central America to themselves afford the cost of going green.

The longer it takes to adequately vaccinate these regions and provide them with sufficient financing, the greater the risk that dealing with climate change and the plastic waste crisis remain at the very bottom of their list of priorities.

Greenhouse gases don’t respect borders. Neither does plastic waste as it circulates around the oceans.

Supporting the developing world to achieve adequate vaccination levels therefore does not represent charity. It is instead a common sense approach that would benefit everyone.

The extreme downside outcome that nobody wants

Let us think of the worst-case outcome as we imagine what the world might look like in 2025.

Developed-world oil, gas, refining and petrochemicals companies confront increasing investor and legislative pressure to cut their carbon emissions.

The turning point was in 2021 when Shell lost a court case in the Netherlands. The court forced Shell to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions at a faster rate than it had planned. Two environmental activist investors won seats on the ExxonMobil board during the same year.

Ever since then pressure has built and built, forcing the developed world majors to freeze new investments in oil and gas exploration through to petrochemicals.

In existing refining-to-petrochemical complexes, the developed-world majors have also employed greenhouse gas-reducing technologies such as electric furnaces and green and blue hydrogen.

This has given them a competitive edge in the EU market. This is the result of carbon border adjustment mechanisms levied on imports of petrochemicals down to finished goods from countries the EU considers behind the curve in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

While the US hasn’t gone as far as a carbon border adjustment tax, local energy-to-petrochemicals face much more limited sources of financing for non-sustainable investments. They too have also had to invest heavily in emissions-mitigating technologies at their existing plants.

The developed world has meanwhile been crowded out of the petrochemical investments that have had to take place in the developing world, to serve the region’s booming demand growth.

National Oil Companies (NOCs) in the developing world have been able to build lots more crackers, reformers and downstream plants in the old-fashioned ways, with no restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions.

Building new old-style petrochemicals plants in the developing world serves three purposes:

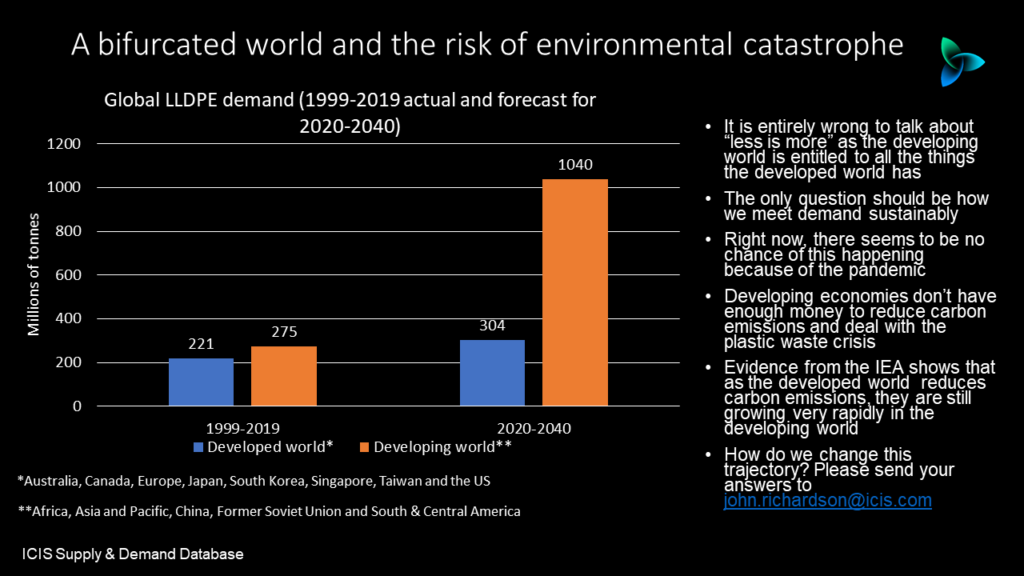

- Meeting, as I said, the huge demand growth that you can see in the chart at the beginning of this blog post. Here I only detail the boom in developing-world demand for linear low-density PE. But the same pattern of growth applies to all other petrochemicals and polymers.

- After the economic devastation caused by the pandemic, the developing world was in desperate need of new industrial projects for the sake of the economic multiplier effect.

- As the developed world has pushed ahead with electrifying transportation, this has created a huge problem for the NOCs because of the fall in oil demand. Petrochemicals are partially helping to compensate for this loss of demand.

And, of course, because oil is so cheap – and because resource-dependent economies need to find a home for their oil – electrification of transport is largely a phenomenon confined to the richer countries.

Anyway, even if the developing world had wanted to push ahead with electrification, it wouldn’t have been able to do so because it didn’t have sufficient funds for the huge investments in new recharging infrastructure.

Sadly, also, no help has been forthcoming from the developed world in providing developing countries with the funding and technologies they need to build adequate plastic rubbish collection and processing systems.

The reason is too many people in the rich world have stuck to the mistaken belief that recycling is the only answer when, in fact, the core of the solution is building adequate rubbish collection and processing systems for the 3bn people who lack access to these systems. Most of these people live in the developing world.

Inevitably, therefore, global greenhouse carbon emissions continue to rise as do levels of plastic waste in the oceans.

Some NGOs keep pressuring the developing world to use less plastics in the first place. But the pushback is, “We want and are entitled all the things you already have from essentials like plastic films that keep food fresh to ‘luxuries’ such as mobile phones, TVs, motor scooters and squeezy plastic tubes of yoghurt that our kids love to take to school. Why shouldn’t we have these things?”

This must not be the outcome. What can we do, as a petrochemicals industry, to stop this from happening?