By John Richardson

SINCE FEBRUARY this year the ICIS petrochemical data has pointed to a significant slowdown in Chinese economic growth.

Data on petrochemicals are always an excellent barometer to the health of any wider economy. The reason is that petrochemicals are used in nearly all manufacturing chains and in many service sectors.

China’s slowdown could be partly reversed in H2 by improvements in supply chain problems that have restricted China’s exports of finished goods during the first half.

And/or the slowdown might well be reversed by another big round of local economic stimulus, if China once again backs away from one its periodic focuses on reducing debts and cleaning-up the environment.

But even assuming container-freight availability gets better in H2 and there are more semiconductors available, what about the potential impact on China’s exports from the cycle out of spending on goods into more services in the developed world? How might this effect China’s export volumes?

“As the first major economy to emerge from the pandemic last year, China benefited from robust global demand for its export goods, which helped China’s export sector continually defy market expectations,” wrote the Wall Street Journal in this 30 June article.

But the newspaper added that Sebastian Eckardt, lead China economist at the World Bank, saw a change in this trend as developed countries emerged from pandemic restrictions – the cycle out of goods into services. I’ve been flagging-up this risk for petrochemicals demand that since last year.

Think of more spending on holidays and less on computers, game consoles, office furniture for homes, washing machines, refrigerators, carpets and tins of paint.

More spending on holidays would support packaging-related demand in polyethylene (PE), general-purpose polystyrene (PS) and PET resins etc.

But reduced spending on durable goods would hurt the durable end-use applications of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, high-impact PS, polypropylene (PP) and other petrochemicals and polymers.

Even assuming another wave of lockdowns in the developed world (we all hope not, of course), might we have already reached peak consumption of computers, washing machines and office furniture as these are only occasional purchases? This is something that I have again been warning about since 2020.

Or could it be that the huge amounts of rich-world economic stimulus guarantee lots more spending on Chinese exports, thereby perpetuating last year’s “China in, China out” story? This involved booming petrochemical imports that were re-exported as finished goods.

This brings us back to logistics. Continued strong demand for Chinese exports might make today’s supply chain chaos even worse, leaving China unable to meet the demand.

Confused? I hope so. All of us should be as this might prompt the right kind of action. We need new and much better models for estimating petrochemicals demand growth. We also need better supply chain intelligence and management.

Now let us look at what the latest data tell us about China’s styrene monomer (SM) demand along with another critical subject for this sector of the industry – China’s likely level of SM imports in 2021.

I will then consider some new scenarios for China’s SM imports in 2021-2031 and the implications for the major Asian exporters to China.

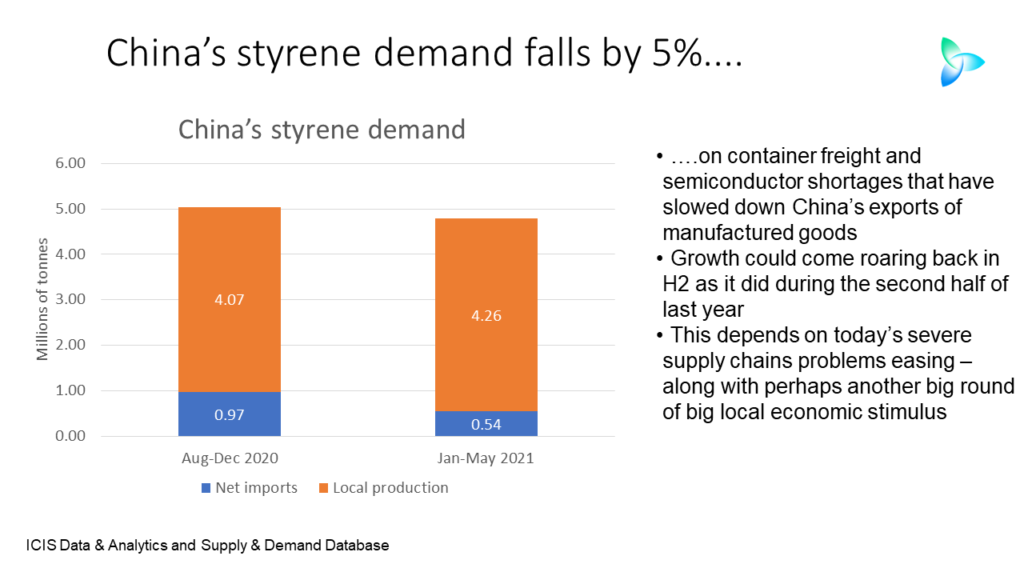

SM demand declines by 5% in January-May 2021

China’s apparent demand for SM fell by 5% in January-May this year to around 4.8m tonnes from 5m tonnes in August-December 2020 (see the above slide). The only valid comparison is with the end of last year.

Year-on-year comparisons of any China economic data give the wrong impression, as, during the early part of 2020, China was in the middle of its worst phase of the pandemic.

Provided the pandemic remained largely under control in China during the early months of this year – and this has been the case – early 2021 was always going to look a lot better than early 2020.

What instead counts is estimating whether the strong growth momentum that China enjoyed in H2 2020 has been fully carried over into this year.

These latest demand numbers for SM – and the latest data for PE and PP – confirm that this has not been the case.

Petrochemicals apparent demand in China comprises China Customs department data for net imports (imports minus exports) and ICIS estimates for local production.

The reason why China’s apparent demand for SM fell by 5% in January-May was a big increase in SM exports. This sharply reduced net imports.

Net imports fell to 540,699 tonnes in January-May 2021 versus August-December 2020 – a 44% reduction. When the same five-month periods are again compared, SM exports were six times higher at 379,307 tonnes.

You might think this merely reflects traders and Chinese producers taking advantage of temporary big gap in Chinese SM prices versus other regions.

But unlike in PP, there was no consistently strong arbitrage between China and any other region in January-June, according to our ICIS Pricing assessments.

The surge in exports might therefore be simply a story of weak local demand for the big styrene derivatives. This was confirmed by my discussions with the market.

The key downstream acrylonitrile butadiene styrene and PS markets were said to be weak on a slowdown in electronics and white goods exports. The polymers are used to make electronics and white goods.

What if the January-May 2021 SM trends in China were to continue for the rest of this year?

Divide January-May apparent demand of 4.8m tonnes by five, multiply by 12, and you end up with 11.5m tonnes of demand for the full year 2021 (See the slide below).

This would be 1% lower than my latest estimate for 2020 demand, which is 11.7m tonnes. I now think that last year’s demand grew by 12% over 2019 after some inventory adjustments, down from an earlier forecast of 18%.

Minus 1% demand growth 2021 would compare with our base case forecast of 4% growth for this year. This would leave consumption 608,000 tonnes smaller than our 2021 base case, when you look at the exact numbers.

China’s imports in 2021 could be 38% lower than last year

The other component of January-May apparent demand was, as I said, local production. This rose by 4% over August-December 2020 to approximately 4.3m tonnes.

If you again annualise this local production, you end up with domestic output for the whole of 2021 of 10.2m tonnes.

This implies a local operating rate of 75% over this year’s capacity of 13.7m tonnes/year – 24% higher than last year’s capacity. In 2020, capacity increased by 20% over 2019.

China doesn’t just run its petrochemical plants to make money. The government’s national objectives also determine operating rates, so it is reasonable to assume a quite high operating rate of 75% in 2021 even if market conditions remain weak.

January-May 2021 imports only (not net imports) totalled 730,354 tonnes. Divide this number by five and times 12 and you get to annual imports of around 1.8m tonnes. This would be 38% lower than last year’s actual imports of 2.8m tonnes.

Now let us consider my revised outlook for China’s SM 2021-2031 imports, which you can see in the slide below (here are some earlier scenarios).

I have assumed that none of the 3.2m tonnes/year of unconfirmed capacity we have listed in our ICIS Supply & Demand Database goes ahead. This is capacity where financing, approvals and feedstocks etc. have yet to be obtained.

I assume that demand growth bounces back to plus 6% in 2022 after this year’s decline of 1%. Growth in 2021-2031 averages 4% as operating rates average 74%.

China’s imports fall to just 300,000 tonnes in 2022. In 2023-2029, China is an exporter before returning to a small import position in 2030-2031.

I must stress again – as this so, so important for our industry – China dominates global petrochemicals and polymers imports.

Its levels of self-sufficiency across several products must therefore be constantly monitored given China’s major programme of capacity additions.

In the case of SM, ICIS estimates that China accounted for 69% of total 2020 global net imports. This is amongst the countries and regions than import more than they export.

Major blow to Middle East producers, significant blow to Asia

China’s top six SM import partners in 2020 by order of size were Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea. In January-May 2021, the same six countries dominated imports in a slightly different order.

Now let us take the ICIS Supply & Demand Database estimates for total SM production in these countries in 2020 and compare this to imports from the countries which was recorded by China.

The standout country most of at risk from China’s self-sufficiency is Kuwait as Chinese imports accounted for 84% of our estimate of its 2020 production. This is followed by Saudi Arabia at 53% and Singapore at 26% – the most exposed of the Asian countries.

Conclusion: keep an eagle eye on the data

Absolutely, my downside for China demand may very easily turn out to be way too pessimistic. Chinese petrochemicals consumption in general saw a strong rebound in H2 last year and history could easily repeat itself.

And nobody knows, of course, if all the 24% of extra Chinese SM capacity due onstream this year will come online and how new and old plants will operate.

But we live in exceptional times. In the 24 years I’ve been covering this business, I have never seen supply chain chaos like this.

Neither I have ever seen so much demand uncertainty and complexity as we see today. Many of my friends in the industry who have longer careers in petrochemicals say the same things.

And we have never been in the position that so much petrochemicals capacity has been built in China across a number of products that complete self-sufficiency is a possibility.

It is essential that you therefore keep on top of developments in Chinese petrochemicals supply and demand using the ICIS data.

You also need to think long and hard about the implications of these market disruptions from a producer and buyer perspective.