By John Richardson

AS I’VE BEEN arguing for the past ten years, the global petrochemicals industry is enormously, disproportionately, reliant on growth in and exports to just one country. No prizes, I am afraid, for identifying that country as China.

My colleagues from our analytics and consulting team have calculated a remarkable summary of what this meant for polyolefins in 2020:

- China accounted for 38% of global consumption.

- It used more than 3.5 times as much as the second largest country (the US).

- Chinese consumption alone was larger than the combined consumption of the next twelve countries.

- Gross China imports are larger than the total consumption of any other country.

This is why it is essential to delve deeper into China by assessing demand and supply province by province. This will enable us to produce nationwide numbers of greater value. Too much analysis is on national-level numbers only.

A scenario-based approach is also crucial as, of course, the future has always been inherently uncertain – even more so now given the challenges for China that I’ve documented over the last decade.

These include an ageing population, increasing geopolitical tensions with the US and the new variables created by the pandemic.

Both demand and supply of petrochemicals in China will be profoundly influenced by these headline challenges.

For instance, China may push even harder towards petrochemicals self-sufficiency – and it is already pushing very hard – in order to improve the cost competitiveness of its vast manufacturing industries.

Why might improved cost competitiveness be a big priority? Because an ageing population is eating into China’s wage-cost advantages.

An ageing population and tensions with the US could result in the creation of the world’s biggest-ever trading zone centred on the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI).

As I’ve argued for the last five years, we could end up with the BRI region as an entirely self-sufficient zone petrochemicals zone. The US could be shut out of being able to export to not only China, but also to most of the rest of the developing world.

Cheap feedstocks might therefore only be a future competitive advantage if plants are also located in the BRI region.

A five percentage-point global demand gain in one month, thanks just to China

Further underlining my argument on the magnitude of China’s influence is our latest estimate for China’s PP demand in 2021. along with the global implications of this estimate.

During H2 2021 compared with the second half of last year, China’s PP demand fell by 6%. This indicated that if the H1 trends continued for the full year, demand for 2021 would only reach 32.3m tonnes.

This would still be 300,000 tonnes larger than in 2020. But 32.3m tonnes would compare with our base case estimate for 2021 demand of 34.5m tonnes.

What a difference a month can make. Our latest estimate for Chinese demand – for January-July 2021 – points towards only a 2% decline in consumption versus the last seven months of 2020.

If the January-July 2021 trends were to continue for the rest of this year, annual consumption would total a considerably healthier 32.8m tonnes.

Given that China would account for around 40% of total global demand with its demand at either 32.2m tonnes or 32.7m tonnes in 2021, the higher number would make a big difference.

At 32.2m tonnes of Chinese demand in 2021, I estimate that global demand would rise by 1.7% over 2020 to global demand of 79.2m tonnes.

At 32.7m tonnes, the global percentage increase would be 2.2% to 79.7m tonnes, assuming growth in all other regions remains unchanged compared with my earlier forecast.

In other words, global demand growth prospects have improved by five percentage points in the space of just one month because of events in China.

The chart below shows my latest estimate for Chinese demand in 2021 and demand in all the other regions in millions of tonnes – along with the percentage shares of the global total of 79.7m tonnes.

Too early to call a solid demand rebound, though

But what has gone up could easily go down. When you examine China’s January-June 2021 demand data in detail, you find that one of the reasons for the improvement is an 8% surge in local production (see the chart below) compared with a 6% rise in H1 2021.

The collapse is net imports wasn’t quite as bad in January-July 2021 versus H1 2021 – down by a “mere” 47% versus 54%.

(Just a reminder: you add local production to net imports to get to demand).

Around 60% of China’s increase in PP capacity in 2021 is due onstream in H2. China’s capacity is due to increase by 13% in 2021 over last year to around 35m tonnes/year. So, this could well explain the pick-up in the growth of local production from 6% to 8%.

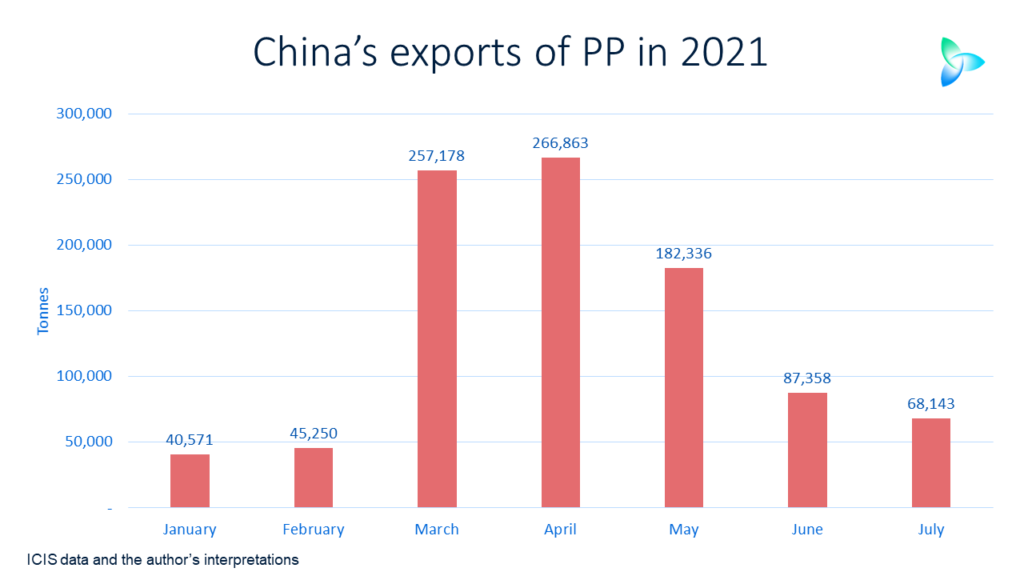

Now look at the chart below which shows China’s exports of PP so far this year.

in January-July 2021, exports have totalled 947,698 tonnes versus 424,746 tonnes during the whole of last year, reflecting the rise in Chinese capacity and weaker-than-expected Chinese demand growth.

The weaker growth is because China’s finished goods export-led economic recovery in H2 2020 has come off the boil due to container freight and semiconductor shortages.

But note the fall in PP exports since their April peak, which is likely to be the result of rising freight costs and weaker Asian demand as most of China’s exports are intra-Asian.

So perhaps the 8% rise in local production in January-July 2021 points towards overstocking in this weaker-than-expected demand growth environment, with pressure on inventories building because of a reduced ability to export surpluses.

Also, China accounted for 43% of total global net imports in 2020. This was amongst the countries and regions that imported more than they exported.

The latest data show that China is still on course to see imports drop to around 4.4m tonnes this year – 33% lower than 2020’s 6.6m tonnes.

Bored by perhaps the excess of detail in this post? If so, the essential question is this, “do you have anything better to do than study the minutiae of China’s petrochemicals markets? As I’ve just demonstrated your answer should be an emphatic “no”.