By John Richardson

IT USED TO BE the case that petrochemicals demand could be considered as a global whole. But this was before the pandemic.

The failure of the rich world to adequately support the developing world in providing sufficient vaccines has led to a form of de-globalisation

This is the divided chemicals world I’ve been highlighting on the blog since February. The big question is of course how long it will take to return to normal. By 202e?

A full recovery by then assumes that the Duke Global Health Innovation Center in Durham, North Carolina is correct when it says that the world will be adequately vaccinated by 2023.

But this looks like a stretch when we again examine the latest data on country-by-country complete vaccination levels from Our World in Data.

Bookmark this relevant part of the Our World in Data site, as progress towards adequate vaccination levels of 80% in the developing world ex-China will be a key determinant of when petrochemicals demand growth in the region bounces back.

I feel there is now no doubt that our 2021 base case assumption of V-shaped consumption recoveries in Africa, the Middle East, the Former Soviet Union and Developing Asia and Pacific won’t happen.

These regions together comprise what I refer to as the Developing World Ex-China, as China is far from being a typical developing economy.

Failure to come anywhere close to adequate vaccination levels has resulted in the “extreme” poverty and “middle income effect” drags on growth, which I’ve detailed in previous posts, persisting into 2021.

And, as I said, resolving the developing word vaccination issue by 2023 right now seems a big stretch.

The experience of Israel, a fully developed economy, is sobering. Israel has discovered that third booster shots of vaccines are necessary.

“Holders of Israel’s vaccine passports must get a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine within six months of their second dose or lose the so-called green pass that allows them more freedom,” said the Wall Street Journal.

Developing countries are struggling to administer two shots of vaccines per person because of lack of supply and weak infrastructure.

If it is proven that a third short is medically essential, this suggests a long, long delay until economic growth and therefore petrochemical demand conditions return to normal in poorer countries.

The Developed World Plus China is a vastly different proposition. As I’ve detailed on the blog since September last year, the region’s growth in domestic petrochemicals demand has become divorced from fluctuations in GDP.

Regardless of the success in controlling the pandemic, domestic demand will remain strong in the Developed World Plus China.

But China is seeing a significant slowdown in petrochemicals growth relative to last year because of another effect of the failure to adequately vaccinate poorer countries: persistent container freight disruptions.

Low vaccination rates in Africa etc have helped the Delta variant thrive – hence, recent lockdowns at Chinese container ports with further lockdowns likely.

And as my ICIS colleague, Will Beacham, writes in this ICIS news article, the pandemic is just one of several disruptions to the container freight business:

- The shipping industry is very cyclical and prior to the pandemic, overcapacity and poor profitability contributed to consolidation and bankruptcies in the sector. The number of shipyards globally has collapsed, with empty order books until late last year when the current crisis kicked off.

- Although a fleet of new container ships is on order, it will take three to five years for these to reach completion, leaving the system short for the foreseeable future. Investment in port facilities has also been inadequate to handle the numbers of containers on the latest and largest ships.

- In the second half of 2020, the shipping industry was caught by surprise by a rapid rebound in demand, especially for finished goods from China to Europe and the US. Consumers were stuck at home and spent money on goods rather than services.

- Containers and ships became displaced by this uneven demand and the situation was compounded by the US polar storm and closure of the Panama Canal.

Combine this with the semiconductor shortage – also a result of the pandemic, disruptions in production and perhaps a strike at South Korea’s HMM, one of Asia’s biggest shipping companies – and China may struggle for a good while longer to fulfil overseas demand for its exports.

The 20% fall in China’s exports of finished goods in H1 2021 versus the second half of last year is not because of a lack of demand in the Developed World. As I said, demand is robust and will remain strong.

The decline is instead because China is struggling to meet booming consumption due to the logistics constraints.

For the reasons detailed above, both the container freight and semiconductor disruptions seem likely to drag well into next year, removing the “froth” from Chinese petrochemicals growth that we saw in 2020.

This doesn’t mean that Chinese demand is going to collapse because of strong domestic-driven growth.

But it does mean that the 2021 expansion in consumption across all petrochemicals is likely to be lower than previously expected.

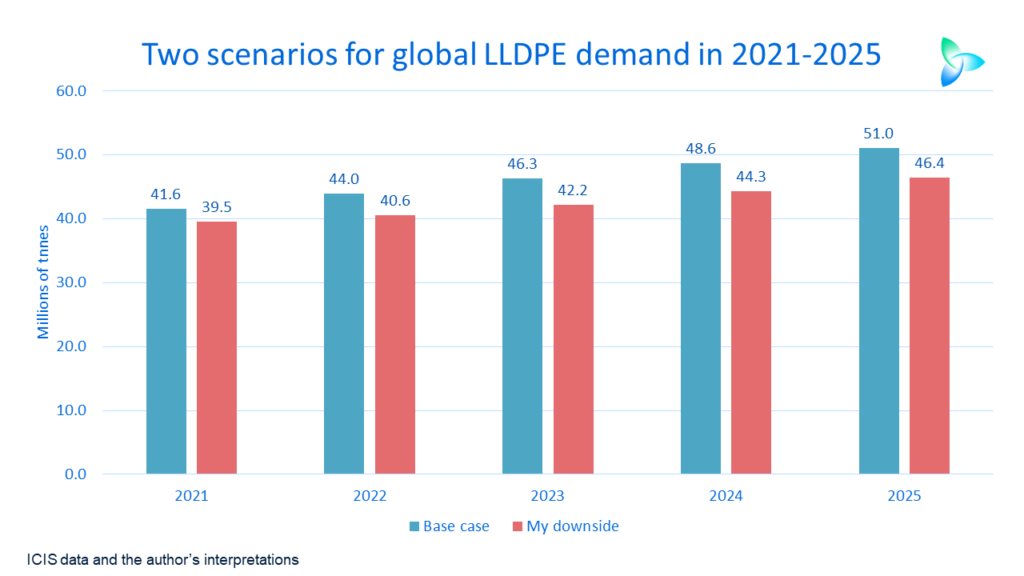

In the light of the above, here is a new scenario for global LLDPE demand in 2021-2025

In my 20 August post, I provided an updated forecast for global high-density polyethylene demand in 2021-2025 which considered the above trends.

But that forecast assumed that the Developing World ex-China would see a strong rebound in demand growth in 2023. I am beginning to believe this was too optimistic.

My latest forecast for global linear low-density PE (LLDPE) for 2021-2025 versus our base case is built around the assumption that in 2021 and 2022, growth in the Developing World Ex-China declines by the same amounts as in 2019 and 2020.

Our base case assumes big recoveries in the region this year – for example, Developing Asia and Pacific growth at 7% in 2021.

Developing Asia and Pacific comprises the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia minus Singapore. Also not included are the other fully developed economies Australia and New Zealand.

My downside for Developing Asia and Pacific assumes 7% declines in growth in both 2021 and 2022 – the same as the decline our base case estimates for 2020 over 2019.

In 2023, I see growth across the Developing World improving but at still very low or negative levels. Using Developing Asia and Pacific as an example again, I see growth at -3%.

Then in 2024 and 2025, my downside assumes that the recovery will be in full swing as the poorer countries make up lost ground. Developing Asia and Pacific growth is at 7% during each of these years.

As for China, it seems clear to me that 2021 growth is going to be lower than our base case forecast of 8% over last year to a market of 15.8m tonnes.

I assume that the trends during January-July continue, resulting in 2021 demand at 14.8m tonnes – which would represent flat growth over 2020.

But I then assume the same annual patterns of 2022-2025 growth in China as our base case – and average growth during these four years of 7%.

This makes a huge difference as between 2021 and 2025 China would account for around 40% of global demand under both our base case and my downside. North America would be in distant second place at approximately 16%.

Cumulative Chinese demand in 2021-2025 under my downside would be 6.8m tonnes lower than our base case.

Back to Developing Asia and Pacific. Because of the depths of further demand declines in 2021-2023, the region’s cumulative demand would be 8.8m tonnes lower than our base case.

Put this together and you get the slide at the beginning of this section of the blog. In summary, my downside would see cumulative demand at 18.5m tonnes lower than our base case. Annual growth would average 3% rather than 5%.

From the perspective of producers in Europe and US who continue to enjoy exceptionally tight supply and strong demand, the above chart will cause few concerns because, as I said, we live in a de-globalised divided world.

But, firstly, the failure of the rich world to provide adequate vaccine support to poorer countries is morally unconscionable, in my opinion.

Secondly, the longer that the vaccination crisis goes on, the greater the lost growth opportunities.