By John Richardson

ON THE PLUS side of the H2 China polyolefins demand ledger are the Golden Week Holidays between 1-7 October and the Singles’ Day internet sales promotion event on 11 November.

The second half of the year always includes China’s peak manufacturing season, which runs from August-September until October, when Chinese factories ramp up output of finished goods to get goods on the shelves in time for Christmas.

The weight of history is on the side of a stronger second half. The ICIS data show that demand for polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) in China has been stronger in every H2 compared with H1 every year since at least 2010, which was far back as I took our numbers, as I have a life. It took ages to go back as far as 2010.

But the big BUT hanging over markets as we approach the end of 2021 is Evergrande.

Last week, bond trading in the heavily indebted real estate developer was halted as concerns increased that it might go bankrupt.

The real estate giant has warned that it may default on $305bn of debts and the BBC wrote that it owned 1,300 projects across 280 cities.

There is strong evidence to suggest that Beijing could allow Evergrande to go under as the government attempts to move beyond an era of a red-hot property market, fuelled by extremely risky speculation, that Xi Jinping believes has created unacceptable levels of income and wealth inequality.

The aim is that by 2035 (Xi’s retirement age), China will have become a “socialist country – prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious,” wrote the latest PH report.

This is a longstanding objective, the second part of Deng Xiaoping’s vision after allowing “people to get rich first”.

But Deng’s approach had led to a Gini coefficient of 38.5% – just below the US at 41.4% and well above Germany at 31.9%, added the PH report.

Xi’s desire for greater equality, under the slogan “common prosperity”, was not just a marketing slogan, said the report.

The report was in line with Caixin magazine which wrote that common prosperity would “reshape the societal structure from a pyramid-shaped structure to an oval-shaped one with the widest part representing the middle class”.

This policy shift has so many implications for global petrochemicals given that China is at the very heart of global demand. It would be ridiculous to attempt to cover all the angles in one post.

Before I therefore focus the rest of this post just on the potential implications of events at Evergrande in Q1 and into early 2022, the slide below is a reminder of the critically important global context.

China’s role in driving global petrochemicals demand saw its first phase of rapid acceleration begin in late 2001, when China was given admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Tariffs and quotas that had limited China’s exports to the West were removed because of China’s admission to the WTO, allowing China to take greater advantage what were then unbeatably low labour costs and excellent infrastructure.

Then in 2009, China’s role received another boost following Beijing’s huge economic stimulus package introduced to combat the effects of the Global Financial Crisis.

This triggered a boom in personal wealth over more than a decade, which has substantially driven the red-hot property market.

Interestingly, 2008 and 2009 were the years when China overtook either Europe or North America to become the world’s biggest consumer in nearly all the petrochemicals.

A third boost to China’s role in driving global demand was delivered by the “China in, China out” story during the second half of last year, which you can see in the table at the bottom of the above chart.

This involved a big jump in Chinese imports of PE, PP and other petrochemicals, and in overall domestic demand, as China’s exports met the lockdown needs of rich countries for physical goods.

What is extraordinary is how far behind the rest of the world is in global shares of demand in the above products. The nearest second-place contender in 2020 was the Asia and Pacific region at an average of around 20%.

What you need to consider in Q4 and into early 2022

Let me focus here on what you need to worry about until this end of this year and into early 2022.

In another post next week, I will consider the longer-term implications for the Chinese economy and with it the country’s petrochemicals consumption of Evergrande and “common prosperity”.

What would immediately happen if Evergrande were to go under? Having talked to some wise “China hands”, I think it is unlikely that the Chinese financial system would be at risk.

It is thought that Evergrande could become a state-owned enterprise with the land and property sold at lower prices to the public. This would be in line with the “common prosperity” objective.

But while a systemic financial sector crisis might not happen in China, more than 25% of the country’s GDP is driven by real estate.

An Evergrande managed failure would lead to depressed property construction in general over the next few months, and quite likely further declines in real estate sales. Sales fell by 16% in the four main Tier 1 cities.

This would of course lead to less demand for the chemicals and polymers that go into construction. Think of less demand for high-density PE and PP pipes.

“A collapse of Evergrande will have a large impact on the job market. It has 200,000 staff and hires 3.8 million people every year for project developments,” wrote Reuters.

Retail sales growth may also weaken further on the anxiety created by a property slowdown and lost personal wealth, with negative implications for polyolefins demand.

In August, retail sales grew by 2.5% which was well below the 7% forecast by analysts. August’s increase was the lowest in 12 months.

The weak August retail sales number – along with industrial production that expanded at a lower-than-expected rate – was further evidence of an economic slowdown that began in February.

The ICIS China PE and PP demand data has shown declines in consumption growth since February this year.

This initially appeared to be the result of container freight and semiconductor shortages leading to a slowdown in Chinese exports.

More recently, the slowdown has been compounded by new outbreaks of coronavirus, firstly in Nanjing in July and then in Fujian. The new outbreaks are also reasons for China’s weak retail sales growth.

“Insofar as China maintains a zero-tolerance policy towards COVID-19, that leaves their economy vulnerable to any potential local outbreaks because they will have to shut down,” Carlos Casanova, senior economist at UBS told the Financial Times.

He added that it had proved more challenging than expected to raise retail sales following China’s major wave of lockdowns in Q1 this year.

And now, as I said, we have the Evergrande crisis on the negative side of the H2 demand ledger. Weak consumer sentiment could lead to disappointing Golden Week and Singles’ Day sales numbers.

Here is the thing as well: whereas polyolefins demand in every H2 has been stronger than in every H1 since 2010, 2020 was a statistical anomaly.

Between 2010 and 2019, average demand growth in all the H2s over all the H1s was 3%. But in in H2 2020, growth surged to 9% over the first half because, of course, H1 of last year was when the pandemic was at its worst in China.

And what mainly caused this extraordinary H2 2020 rebound? It was exports as China supplied most of the goods the rich world needed or wanted during lockdowns, such as computers, game consoles and office furniture to convert homes into offices.

This was bubble growth. When every bubble is inflated it will always eventually deflate. I suspected at the time that this would happen in 2021.

The container freight and semiconductor shortages have sucked the air out of the bubble at a rapid rate.

In H1 2021 over the first half of last year, China’s exports by value were up by 2%. This reflected inflation.

But exports by volume in tonnes were down by 4%. This obviously meant less demand for polyolefins in tonnes that were either made domestically or imported for processing into finished goods for exports.

Here is another thing: container freight shortages look set to persist into 2022.

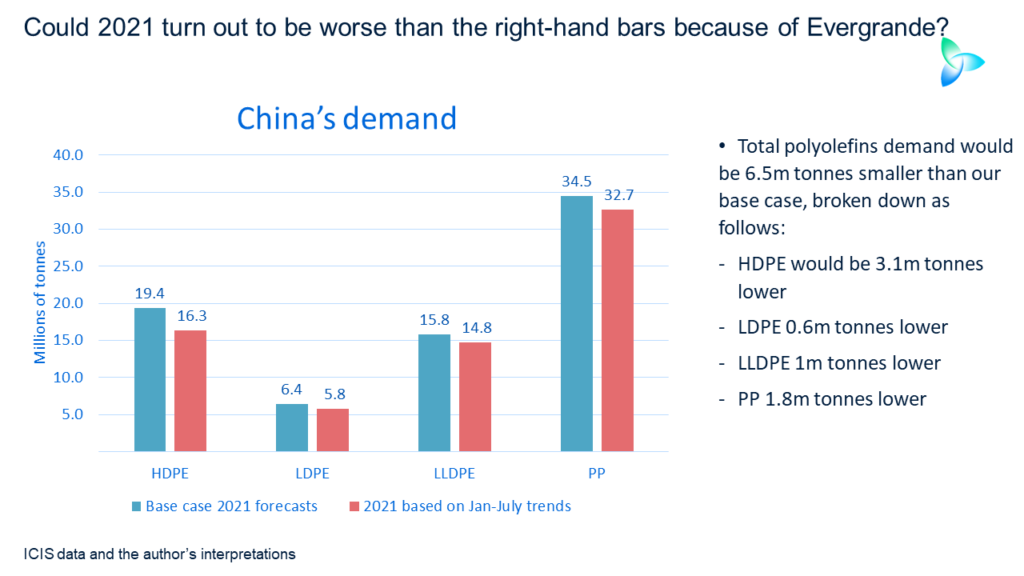

Add this all up and the right-hand bars in the slide at the beginning of this section of the post – showing what would happen to China demand if January-July trends were to continue for the rest of this year – could turn out to be overestimates.

The left-hand bar charts showed our base cases for 2021, indicating a potential substantial shortfall.

The sting in the tale of this post is that Evergrande could lead to global financial market problems given the amount of Evergrande debt that is held offshore – and the amount of Chinese corporate bonds in general that are held offshore.

As my fellow blogger Paul Hodges points out, margin debt versus the S&P 500 is at all-time high (see the chart below).

But we have been here before on several occasions since 2008, when inflated financial markets looked as if they were heading for long-term corrections only for events to prove otherwise.

So, I will stick to what I know, understand and feel confident in commenting on and it is this: there is a strong possibly of Chinese polyolefins demand growth further weakening during the rest of 2021 after declines in January-July.

As always, please be careful out there.