By John Richardson

ONCE AGAIN, PLEASE don’t say I didn’t warn you. The switch from inflation to disinflation or deflation is already well underway, a lot sooner than my prediction of Q1 next year.

American retailers, having spent months scaring customers with stories of shortages, were trying to lure them into stores with offers of discounts, extended sales and faster deliveries, wrote John Dizard in this Financial Times article.

But Dizard said data suggested that the customers were not interested. This could indicate that the cycle out of goods and into services, the result of the end of lockdowns, is well progressed. Demand destruction from the big jump in inflation also appears to be further dampening consumer spending.

The October Chicago ISM inventories index rose by 8.5 points to 59.6, the highest since the US autumn in 2018. Order backlogs for manufacturers in the area dropped 18.8 points to 60.8, which is 6 points below the 12-month average, wrote Dizard. The Chicago ISM is seen as a reliable nationwide business barometer.

Susan Sterne, president of US-based Economic Analysis Associates, has spent years tracking US buying trends, inventory levels, labour force levels and sentiment indicators.

High inventories appeared to be “more of a shortage of demand than supply, which is consistent with what the consumer says about current buying conditions,” said Sterne.

But don’t necessarily expect the same level of support to demand from US government stimulus as we’ve seen over the past 18 months. Joe Manchin, US Democratic senator, may successfully block the passage of President Joe Biden’s $2tr Build Back Better spending programme that includes big new social and climate change spending proposals.

But Manchin, like a lot of people, might be in danger of fighting yesterday’s battle. His objections to Build Back Better are based on inflation. But his views change when it commonly accepted that the inflation scare is over.

More evidence of lengthening supply came from Dell, which reported an extraordinary 60% rise in its year-on-year inventories for the nine months until September to $5.4bn. During the same nine months, HP’s inventories rose by 33% to $7.9bn.

This is not just the result of weakening demand. It is also because of the “bull-whip” effect: big surges in stocks when raw materials and finished goods suddenly arrive, which have been held up for a long time in today’s dysfunctional supply chains.

And, as one of the few things you can be sacked for as a purchasing manager is running out of stocks, it seems likely that purchasing managers in many countries will have over-ordered to compensate for delays to deliveries caused by container and trucker shortages and clogged-up ports.

This raises the question of how much stocks are at sea or in port warehouses. When they arrive, this will add to deflation or disinflation. It seems logical that stocks in transit will be huge because of a) hedging against supply chain disruptions and b) hedging against further price rises by buying more than is immediately needed.

And there’s the long-term China structural slowdown.

Last week’s reaction to Evergrande’s default on its debts was incredibly muted. I suspect that this was because other events “crowded out” the news.

But this is still a massive, massive deal as Beijing’s decision to allow Evergrande to default underlines its cast-iron commitment to Common Prosperity. An indication of this commitment is the chart below, from fellow blogger Paul Hodges, which shows China’s decline in “shadow” or speculative lending.

“There is no sign of Beijing panicking from the November’s lending figures,” said Hodges.

“Since China’s real estate bubble began to burst, local government financing is up – as they bought more unsold land from themselves,” he added.

“But shadow banking, which financed the bubble, stayed in the doldrums. 2022 will see the implications of the burst hit global commodity markets as China’s speculative property demand disappears.”

I couldn’t agree more with this last statement. The speculative froth has been removed from China’s economy. As increased lending to local governments indicates, this will be a stable and well managed economic transition. There will be no collapse.

But as I have been arguing since September – and as the chart below summarises – China’s economic growth will become less commodity intensive because of the Common Prosperity policy shift. The chart also includes what this could mean for China’s polypropylene (PP) demand.

Looking at the PP forecasts in detail, our base case sees annual demand growth averages 5%.

But what if it were to average 3%? Cumulative demand in 2021-2025 would be 14m tonnes lower than the base case. The second downside, with growth at just 2%, would leave cumulative demand 20m tonnes lower.

This is a huge deal as in 2020, China accounted for 41% of global demand – way ahead of any other region.

Weaker Chinese growth in demand for commodities, including petrochemicals, is therefore another major global deflationary or disinflationary trend that’s already in play. Partly because of Common Prosperity, China’s polyethylene (PE) demand growth in 2021 is likely to be negative over 2020. PP growth will still be positive, but lower than had been forecast.

As we drill down further into what all this means for polyolefins, let’s analyse PP and PE supply.

China to drive global PP oversupply as the US drives global PE oversupply

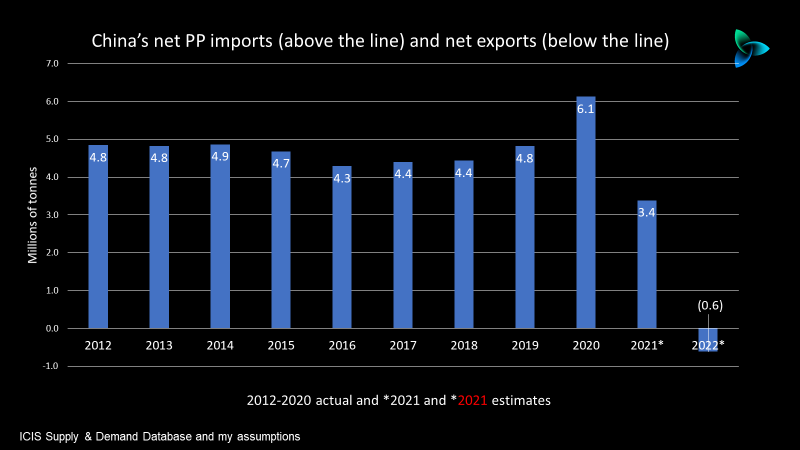

The chart below, from this post last week, shows how China could become a net exporter of PP in 2022 from a net import position of 6.1m tonnes as recently as 2020.

There is nothing new here as we saw a similar dramatic shift five years ago in purified terephthalic acid (PTA) in a very short space of time, China swung from being the world’s biggest net importer to being a net exporter.

And like in PTA five years ago, few people see this potential for PP. The conventional view is that China will still be in a net import position of some 3-4 tonnes a year of PP from 2022 until the end of the decade.

Perhaps. But just imagine the psychological impact on markets if I am right and China unexpectedly becomes a net PP exporter next year. This would obviously dampen market sentiment.

But never mind psychology, just look at the physical impact of this shift, illustrated by the chart below.

Our base case sees China still importing 3.6m tonnes of PP in 2022, 33% of the global total of around 11m tonnes, just slightly behind Europe including Turkey at 3.7m tonnes at 34% of the total.

My alternative outlook assumes lower Chinese demand growth in 2021 and 2022 on Common Prosperity – three percentage points lower in 2021 and two points lower in 2022 than the base cases. I have raised 2022 operating rates to 86% from our base case of 82% to get to net exports of around 600000tonnes in 2022.

My numbers might, of course, be wrong. But the minor scale of my adjustments shows just how easily China could tip into net exports. And without China, the remaining net import market would fall to 7.4m tonnes, creating a much more crowded space.

Whereas Chinese PP supply could dominate the global market in PP in 2022, it could well be US PE supply as the chart below reminds us.

High-density polyethylene (HDPE) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) [KJ(S1] inventories in the US are reported to be high, as local production gets back to normal following this year’s exceptional production losses.

Chemical Data, the ICIS service, estimates that in January-November 2021, US exports as a percentage of overall production was at 23% because of production. Under normal operating circumstances, exports as a percentage of production need to be at 33%. Go figure.

Conclusion: A fall in container freight rates the final piece of the jigsaw puzzle

On the theme of oil prices, before we move onto containers, I believe that prices will either fall because of increased supply resulting from the political pressure on OPEC+ to increase output, or because of a global recession as crude now costs more than 3% of global GDP. On several occasions in the past, crude at more than 3% has caused recessions. Let’s hope the former will happen.

Some analysts are predicting a 40% decline in container freight rates in 2022. Last month, I forecast that container rates would fall next year on the cycle out of demand for goods and into services due to the easing of lockdown measures.

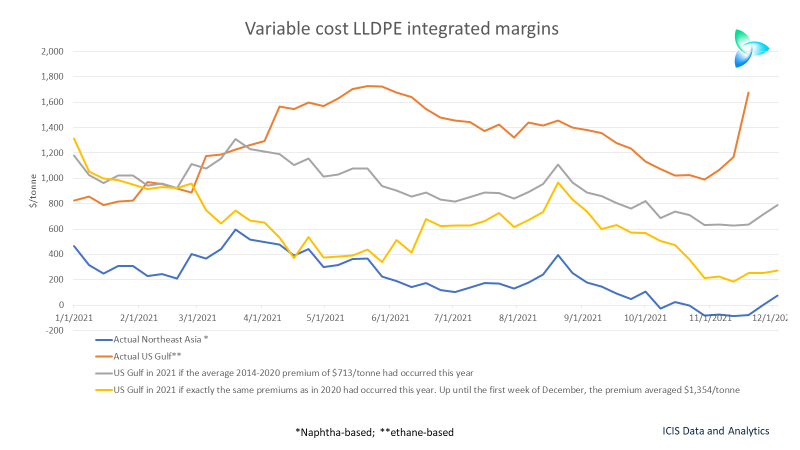

This would be the final piece in the jigsaw puzzle. When lower container rates click into place, I see a picture emerging of polyolefins trade becoming much more global again. Look at the chart below and think what this means, whether you are a producer or a buyer. Consider the box at the bottom of the chart.

Now look at this last chart below, again showing linear low-density PE (LLDPE) margins, but this time focusing on the US. The same pattern of margin divergence – huge premiums in Europe and the US over Asia in 2021 – applies to the other grades of PE and PP.

I see margins in 2022 normalising towards Asian levels as the broader deflationary or disinflationary trends kick in.