By John Richardson

THE OMICRON outbreak is piling further pressure on already extremely stressed supply chains as Europe struggles to cope with the highly infectious variant.

As my ICIS colleague, Tom Brown, said in this ICIS Insight article, tapping into market intelligence from our pricing editors: “The supply chain pressures that have dogged the European chemicals sector since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic are hitting harder than ever in the run-up to the holiday season, as governments respond to rising infection rates.”

He added that lead times were longer and materials harder to source as transportation, particularly trucking, was disrupted by increased social restrictions and the holiday season. Expect further global container freight disruptions, if you are not seeing them already, as workers at ports fall sick and as ports are subject to lockdowns.

China is returning to a general lockdown after the country saw its first cases of the variant, said The Week in this article. We might therefore see even more supply chain disruptions involving Chinese container ports and its vast export-focused manufacturing capacity.

This will inevitably add to the clamour over inflation. As perceptions always play a large role in shaping what becomes reality, the extra noise over rising prices could in itself cause prices to go up.

Polyolefins purchasing managers may, for instance, buy a lot more resins than necessary to fulfil confirmed customer orders because of worries of rising prices and the timely arrival of supplies.

This would contribute to the idea of strong demand, when, in fact the extra demand would be only “apparent” – ie stock building. But nothing has changed since my post last week on why we may be heading towards deflation or disinflation.

And indeed, Omicron could add to the deflationary or disinflationary pressures through demand destruction, even though additional supply chain disruptions may delay the shift.

I think it is therefore essential that chemicals producers, buyers, traders and logistics suppliers etc prepare for the shift from inflation to deflation or disinflation.

You need plans in place ready to go for when it becomes clear that the transition has begun.

Before I use ICIS data to give you an example of the signals to monitor, let me summarise my arguments for why the shift will occur in the context of Omicron.

US consumers and China’s Common Prosperity

Even before Omicron, US manufacturers and retailers were reporting high inventories on consumer resistance to high prices and the “bull whip” effect: purchasing managers over-ordering raw materials and finished goods because of rising prices and supply-chain delays, leading to sudden surges in stocks when several cargoes arrived at the same time.

High inventories had led to lots of discounts, but US consumer trends experts said buyers were still not interested. This tell us that high prices were causing demand destruction – again, even before Omicron.

The latest $1.8tr stimulus package might not pass Congress because of concerns over inflation. Government stimulus in general is likely to be lower over the next year because rising interest rates will expose high debt levels.

China’s Common Prosperity pivot is the biggest deflationary factor of them all. The pivot is about deleveraging real estate, cutting back on carbon emissions and improving income equality. This means lower GDP growth than many people expect – and lower demand growth for commodities such as oil, chemicals, steel and cement than consensus views.

China totally dominates, way out of proportion to its population size, global demand for everything.

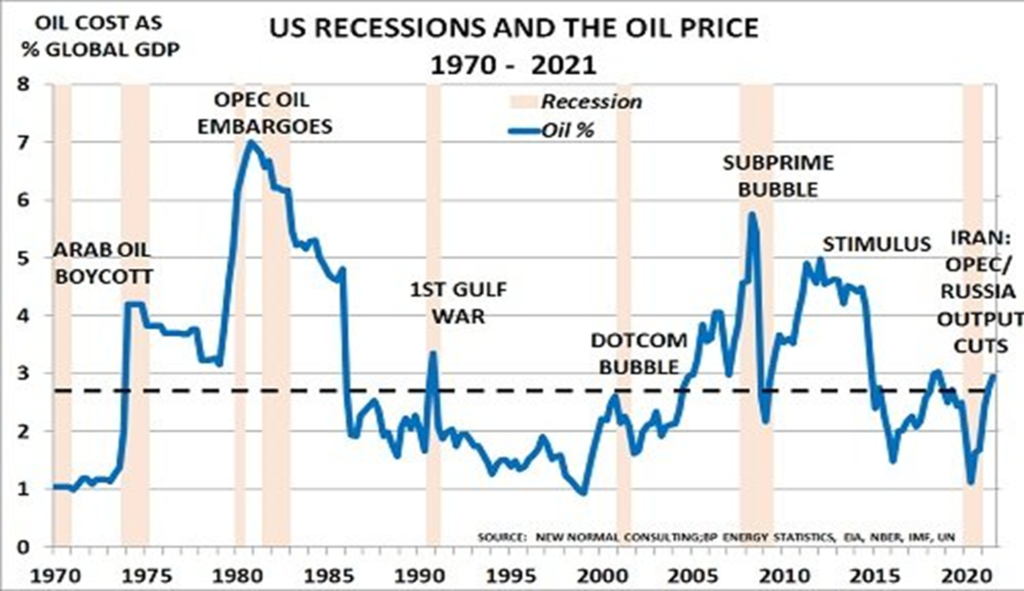

The final piece in the potential deflationary jigsaw puzzle is crude. The cost of crude is now more than 3% of global GDP, which, in the past, has led to recession (see the chart below). Oil prices will therefore, I believe, come down either on successful government pressure on OPEC+ to raise output or on a recession.

Omicron may erode demand, especially in the developing world ex-China. Because of low incomes, lack of government revenues and weak healthcare systems, every outbreak has been bad for the region.

This is unlike the West where previous outbreaks have led to surges in demand for goods as consumption of services have, of course, fallen. But, as I said, I think not in the West on this occasion because of demand destruction caused by inflation and reduced government stimulus ability.

The value of ICIS margins data in showing when the transition has begun

The first chart below compares northwest Europe ((NWE) with northeast Asia polypropylene ((PP) margins.

Today’s second shows the big divergence from historic norms also applies to US Gulf versus NEA PP margins.

Whatever the timing, the above charts cannot, like the supply chain disruptions, continue forever. The charts are the result of abnormal events rather than a New Normal-(a paradigm shift).

The charts reflect a divided world of long supply in Asia and tight supply in the West (you can see the same patterns in other chemicals and polymers from the ICIS margin reports).

Supply is tight in the West because, up until now, demand has been good. But not now for the reasons described above.

Production has also been limited by refinery operating rate cuts resulting from lack of transportation fuels demand leading to reduced feedstock supply and lost US polypropylene (PP) production from extreme weather events. But as transportation demand picks up and US PP production normalises, PP supply in the West will get back to normal.

Meanwhile in China, the long-term slowdown in demand growth because of Common Prosperity is well underway as local capacity increases. Next year could see China move to a PP export position of 600,000 tonnes from net imports in 2021 of 6.2m tonnes.

Distressed supply chains cannot last forever as logistics disruptions are the result of a pandemic that has yet to be brought under control. The pandemic will be brought under control as this becomes just another disease, like flu, that we manage without container freight and trucking delays and shortages.

Some analysts think that much easier conditions in container markets will happen next year as container freight rates fall by 40%.

Once container rates come down to more workable levels, and as delays are reduced, more of the oversupply in Asia will find its to the West as Western production also increases.

This makes the value proposition of buying our margins data clear. When northwest European and US PP margins over northeast Asia (NEA) start declining towards their historic norms we will know the shift is underway.

Our margins and other data can come packaged with all the analytics and market intelligence support that you need.

Getting the timing on these two decisions is, as you know, critically important:

- When PP producers should minimise their raw material purchases to hedge against PP price and margin falls.

- When buyers should reduce their month-on-month resin purchases to benefit from falling prices.

Our support in helping with this timing can save or make you a lot of money. For more details contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.