By John Richardson

UNTIL ALL of us are adequately vaccinated none of us are sufficiently protected is a point I’ve been making since late last year.

So, providing the developing world with the $66bn it needs to be adequately vaccinated – and we appear to be nowhere near raising that figure – would not be just an act of common humanity.

It would also be an act of economic common sense, as no matter how ferocious border closures and lockdowns are, you cannot completely seal large regions of the world off from other regions.

Because big portions of the world remain way short of adequate vaccination levels, as the updated chart below on the left from Our World in Data reminds us, the risk will remain of new and more dangerous mutations of the pandemic developing in inadequately vaccinated populations and spreading everywhere.

Omicron could turn out to be an example of such a mutation.

The chart on the right, from this Vox article I shall quote from later – which is based on Our World in Data and World Bank numbers- shows the vaccination divide in more stark income-level terms.

In the light of Omicron, this doesn’t make me a visionary genius with a highly effective crystal ball.

Instead, as I said, this is just common sense. But, unlike polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) where global supply is long despite highly regionalised markets, common sense amongst many of our political leaders is in very short supply.

The problem is not just about coming up with the money to pay for vaccines and/or supplying the vaccines.

Challenges also include supply chain chaos, a product of the pandemic, that could now get even worse because of Omicron, and lack of enough infrastructure in poorer countries to deliver sufficient shots.

“Hoarding and [vaccine] production constraints are part of the story, but so are less-appreciated obstacles like clogged supply chains and breakdowns in communication between vaccine makers, donors, and recipients,” wrote Vox.

The pandemic had also wreaked havoc on global shipping and supply chains because of the rebound in demand for goods

This had led to crowded ports and trucker shortages. Vaccines, with their delicate handling requirements, as well as vital components like syringes, vials, and stoppers, were vulnerable to these disruptions, added Vox.

Vox made some useful suggestions on how the rich world could solve these issues, including more transparency on the demand for and availability of vaccines, more supplies of vaccines, of course, and more supplies of personal protective equipment and medical personnel.

But in the worst-vase Omicron outcome, vaccine hoarding by rich countries could increase with lower supplies of syringes, personal protective equipment and medical professionals – as, of course, they might not be able to travel overseas – to poorer countries.

On the theme of syringes, the World Economic Forum warned that there was a global shortage of 2.2bn because of supply chain disruptions and on overreliance on production in India and China. India introduced restrictions of exports of syringes in October.

And guess what? Most of the shortages of syringes were in the developing world with as of early November, just 6% of Africans fully vaccinated, the article added.

The scale of the challenge was underlined when Vox, quoting the Kaiser Foundation, said that developing world vaccination rates needed to increase 19 times from current levels in low-income countries to reach the global vaccination target announced by US President Joe Biden.

The target Is for every country to have reached a 70% full vaccination rate by the autumn of 2022. As they say, “Good luck with that”.

New scenarios for PP demand, reflecting the Omicron risks

As always, let me put this into the context of what this could mean for petrochemicals demand, in this case using PP as an example.

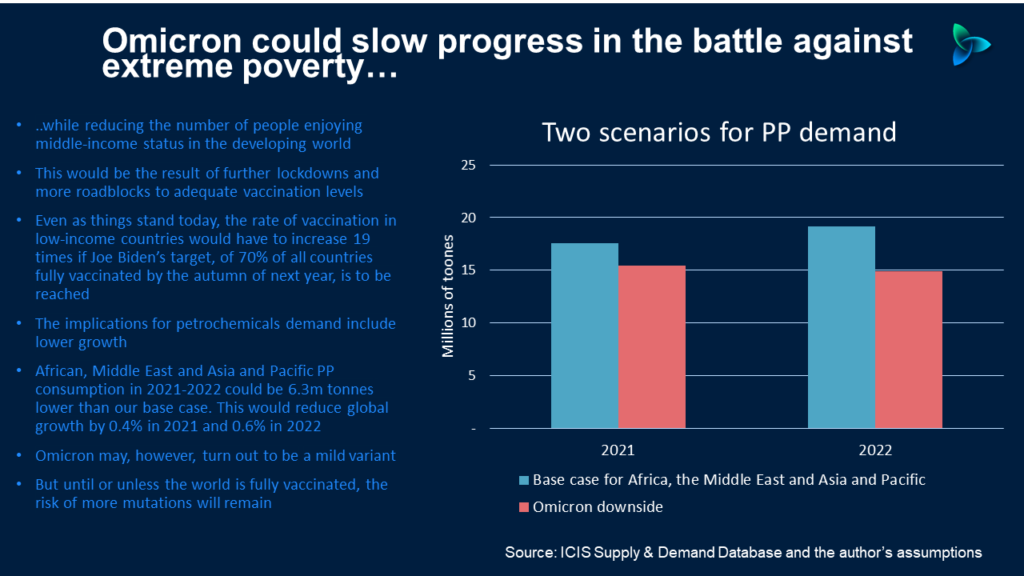

The chart below focusing on three developing regions of the world – Africa, the Middle East and Asia and Pacific – compares our base case demand forecasts, from the ICIS Supply & Demand Database, with my Omicron downsides for 2021 and 2022.

Under the base case, we see African growth in 2021 rebounding to 7% in 2021 from minus 2% last year; Middle East growth is expected to be 5% this year versus minus 3% in 2020; and Asia and Pacific growth is forecast to soar to 10% in 2021 as against minus 4% in 2020.

My downsides assume the same levels of year-on-year negative growth for these regions in 2021 and 2022 as occurred in 2020 over 2019.

The results are as follows:

- Base case demand for the three regions combined reaches 17.6m tonnes in 2021 as against my downside of 15.5m tonnes.

- In 2020, base case demand is at 19.2m tonnes compared with an Omicron outcome of 14.9m tonnes.

- The loss of a total of 6.3m tonnes of demand under the downside would reduce global growth by a percentage point versus our base case in 2021 and 2022 combined (0.4% lower growth in 2021 and 0.6% lower growth in 2022).

Remember that the petrochemicals demand dynamics of the pandemic are very different in the poor versus the rich word.

In poorer countries, lack of enough vaccinations has pushed millions of people back into extreme poverty or has denied them to chance of escaping extreme poverty.

Millions of other people have been unable to move into middle-income status or retain their status.

This equates to lower growth in demand for the petrochemicals that go into all the essential and luxury consumer goods and services, affordability of which is taken for granted in developed countries.

Further, the developing world often lacks adequate healthcare systems, one of the reasons for the slow rate of vaccinations.

Assuming the worst outcome from Omicron, lack of adequate healthcare will force very severe lockdowns, badly impacting all the “day rate” labourers who get paid in cash every day and so would not be able to work.

Developed world demand dynamics have been very different. Instead of demand for polymers declining because of the pandemic, consumption has improved due to booming demand for finished goods bought to relieve the boredom of lockdowns and eating more food bought in supermarkets and less in restaurants.

Demand in all regions has of course benefited from the surge in consumption in end-use hygiene applications.

It is a moot point about whether in the worst-case Omicron outcome, developed world consumption will remain robust.

This will depend on the capacity of rich-world governments to carry on with economic stimulus, another factor behind robust markets, as interest rates potentially rise on inflationary pressures.

Inflation could be made worse by further supply-chain disruptions caused by Omicron.

Consumer spending might take a hit from higher interest rates, leading to stagflation.

But these are themes for a later post, which I will publish next week.

We might dodge this bullet. We won’t have all the data for several weeks to determine how serious Omicron is. With a great deal of luck, this might turn out to be a very manageable version of the pandemic.

But back to my original point. Until or unless the world is adequately vaccinated other mutations seem inevitable. Even if we dodge this bullet, the next one could hit the global economy and with it the petrochemicals industry.