By John Richardson

The first point to make as I write a final review of China’s polypropylene (PP) market in 2021 – also including a further outlook for the rest of this year – is that ICIS supply and demand and trade data is pure gold dust.

The data inform commercial decisions that can save or make you hundreds of millions of dollars, particularly during periods such as this when a major step change is taking place in the China PP market.

The good news, as the chart below shows, is that I believe China’s PP demand grew by 5% last year, higher than my earlier estimate of 4%.

My latest estimate is based on the complete China Customs department import and export data for 2022, ICIS estimates for local production, and my discussions with the market.

But when we compare my latest prediction for last year’s growth with 2020 growth over 2019, there’s a big decline.

I was predicting a 2021 decline in growth at the start of last year because 2020 was so fantastically good, the result of China’s pandemic-related boom in exports of finished goods.

When a bubble growth happens like this, as we’ve seen over the last 20 years of China data, a decline very usually quickly takes place.

But as I keep stressing – as it is so, so important that you understand this – the Common Prosperity pivot added to the loss of growth momentum from August last year onwards. Take note that Common Prosperity is about the following:

- Deflating the real estate bubble.

- Reducing income and wealth inequality through increasing the tax base and spending more on the poorer provinces.

- Lowering carbon emissions, cleaning-up plastic waste and reducing air, soil and water pollution.

The old economic growth model, based on heavy investment, no longer works because of debt, inequality, carbon emission, pollution and China’s ageing population. In my view, there can be no going back. Common Prosperity is here to stay.

Over the short term, there’s the potential for high volatility in local PP demand growth as policies are fine-tuned. But I see the long-term trajectory as downwards.

Over the whole of 2022, however, I believe it is more likely than not that consumption growth will be lower than my estimate for last year of 5%.

Also, don’t forget the risk to growth of China’s Zero-Covid policy which seems likely to last until at least October or November, when a major political meeting is due to take place. The meeting is expected to confirm a third term for China’s president, Xi Jinping.

China’s top PP trading partners: how they fared in 2021

As I was warning would be the case throughout most of last year, 2021 imports saw a steep decline.

They were 27% down over 2020 as demand growth weakened. Local production was also up by 12% last year, according to the latest ICIS assessment. This occurred as capacity rose by 13%.

The top ten countries from which China imported PP in 2021 inevitably therefore saw declines in their trade with China, as the chart below illustrates. Here I’ve given the numbers in tonnes to make them easier to parse.

As you can see, India, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand in percentage terms saw the biggest losses.

But if you are either a producer of PP worried about more competition from these ten countries in 2022 as China’s PP self-sufficiency further increases, or if you are a buyer looking to take advantage, this chart doesn’t tell you the whole story.

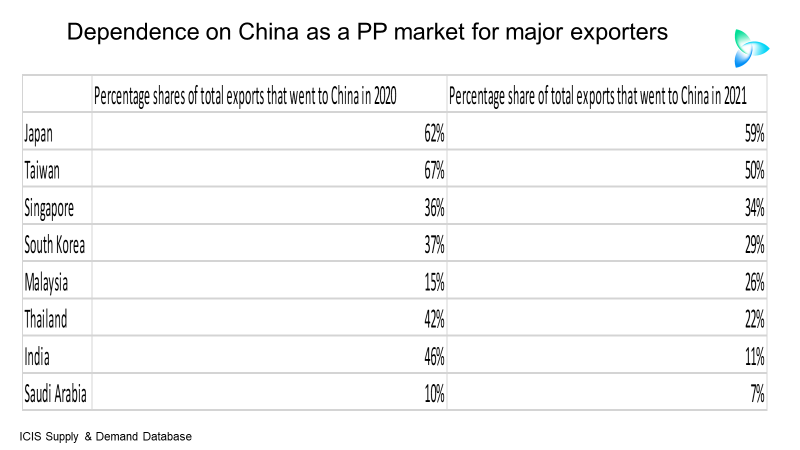

What also counts and gets a little closer to completing the picture is the table below which shows what percentages of total exports reported by eight out of ten of the above countries went to China in 2020 and 2021. The data for Vietnam and the United Arab Emirates wasn’t available.

As you can see, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea remained the top four most-exposed countries. Malaysia’s exposure increased as Thailand and India made big progress in diversifying risk. Saudi Arabia’s dependence fell n 2021 from what already a very low percentage in 2020.

Why the above chart is valuable is because China, as I posted earlier this month, might end up being a net exporter of PP in 2022 (imports minus exports) as its capacity increases by a further 13% in 2202 – and as its demand growth continues to moderate.

Given China accounted for some 40% of global net imports in 2021, the challenges for producers and the opportunities for buyers are substantial.

Also consider South Korea’s capacity is forecast by ICIS to increase by 12% in 2022 over 2021 to 6.3m tonnes/year.

China’s 2021 exports jumped by 227%.

Yes, that’s right, China’s exports increased to around 1.4m tonnes in 2021 over 2020 – an increase of 227%. Illustrating that this is not a one-off statistical anomaly, last year’s exports were 243% higher than in 2019.

The final chart for today shows the top ten destinations for China’s exports in 2021 versus 2020, again in tonnes.

What was remarkable about last year was that despite record-high container freight rates and lack of availability containers, exports still more than doubled.

The reason was partly disrupted logistics. They contributed to sky-high arbitrage which local producers and local and international traders were able to take advantage, when they could find container space.

Note that most of China’s top ten destinations were within Asia, but that Brazil and Peru made it into the top ten.

If the divided pricing world we live in today came to an end later this year, China PP exports would likely be more concentrated in Asia.

I see polyolefins pricing in general in the West falling much closer to northeast Asian levels during 2022 if the container freight market becomes longer – i.e. the end of the divided pricing world.

Note also that Vietnam remained China’s biggest export destination in 2021 because of a free-trade deal between the two countries.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free-trade deal that came into force this month is not expected to affect petrochemicals and polymers trade this year, as there are no scheduled changes in import tariffs.

The trade deal involves Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The level of China’s exports in 2022 will depend on local demand growth and the scale of local production.

Remember that production decisions in China have always been – and I believe will always be – as much political as economic. China may decide to run its plants hard, regardless of individual plants economics in order to increase self-sufficiency for geopolitical reasons.

Conclusion: linking the data together

As I said at the beginning, the ICIS trade and supply and demand data are gold dust. They inform money-making or money-saving tactical and strategic decisions worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

I have just scratched the surface in this post by giving you a snapshot in time of only three sets of data. Missing is ICIS pricing, price forecasting and margins data – along with the constant updates of all the data, with the analysis, that you need to stay on top of markets.

For information on how our ICIS team can support you, including our excellent team in China, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.