By John Richardson

WHEN POLYETHYLENE (PE) and polypropylene (PP) markets become truly global again remains anyone’s guess. But what’s clear in my view is that rebalancing must take place at some point,

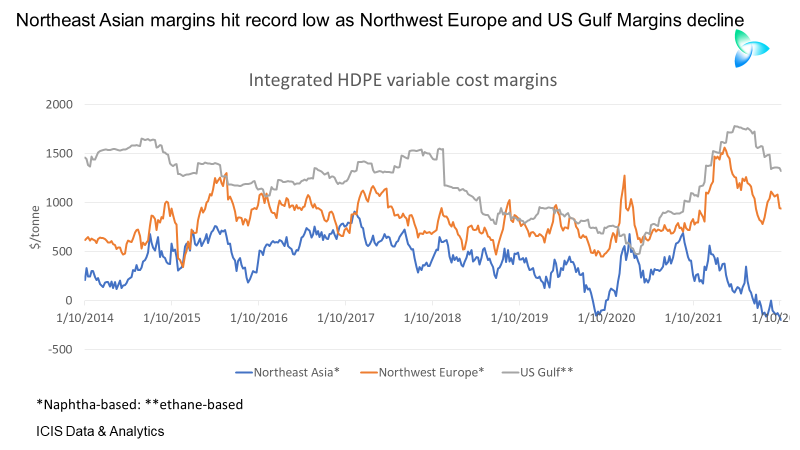

The chart below, using high-density polyethylene (HDPE) margins as an example, illustrates the extent of the disconnect between different regions.

The chart shows the historically high divergence between Northeast Asian (NEA), Northwest Europe (NWE) and US Gulf HDPE margins from January 2021 until the end of last week.

NEA margins reached a record low last week of -198/tonne while NWE and US Gulf Coast margins have fallen from record highs. As I shall discuss later on, US HDPE supply is normalising following las year’s major outages.

There are reports of more availability of US material in Europe because US supply is normalising, as, of course, the highest oil prices since 2014 put pressure on the naphtha-based European producers.

But margins in the West remain historically much higher than those in NEA, as has been the case for the last year, because of the limited ability due to container freight shortages and costs, as I shall discuss in detail later, to move Asian oversupply West.

Demand fundamentals are also stronger in the West than in Asia.

I see weak NEA margins as being largely the result of my forecast for a 6% decline in China’s HDPE demand in 2021 over 2020. The contraction in consumption was the result of Common Prosperity.

The Asian market is being further weighed down during the early weeks of the New Year by the prospect of Common Prosperity continuing in 2022.

Consumption is also being dented by China’s Zero Covid policy (Zero Covid is one of the reasons why global supply chain disruptions may not end anytime soon, which I shall discuss later).

The severe lockdowns resulting from Zero Covid, as China tries to ensure that next month’s Winter Olympics take place without any hitches, are dampening economic activity.

There is a risk that the lockdowns are negatively affecting spending ahead of this year’s Lunar New Year (LNY) holidays, which take place from 31 January until 6 February.

The accepted wisdom is that China won’t relax its Zero Covid policy until at least after this year’s Communist Party National Congress, which will take pace in either October or November, when China’s president, Xi Jinping is expected to be confirmed for a third term.

Big increases in HDPE capacity this year

Keeping cases to a minimum is thought to be important for the government ahead of this key political event.

But the economic cost has already led to several economists to revise-down their estimates for GDP growth. Goldman Sachs, for instance, had cut its forecast for China’s 2022 GDP growth from 4.8% to 4.3%, said the Wall Street Journal in this article.

This may turn out to be over-alarmist, but there some suggestions that Beijing may repeat the nationwide lockdown that took place in February-April 2020.

Other countries are shifting from treating coronavirus as endemic from a pandemic, improving their growth prospects as economies open-up. This clearly doesn’t apply to China.

We must also factor in further big increases in Asian HDPE capacity.

China’s capacity is set to rise by a further 23% in 2022 to 14.6m tonnes/year, according to the ICIS Supply & Demand Database. This would follow a 24% increase in capacity in 2021 over 2020.

In South Korea, ICIS forecasts that HDPE capacity will rise to 4.3m tonnes in 2022, a 27% increase over last year. This would follow a 20% rise in capacity in 2021 over 2020.

The ICIS Supply & Demand trade data show that South Korea exported 1.6m tonnes of HDPE in 2021, only slightly higher than in 2020. The 1.6m tonnes represented only 47% capacity versus compared with exports in 2020 that were at 56% of capacity.

Assume 56% for exports over capacity in 2022 and South Korea’s HDPE exports would this year jump to 2.4m tonnes.

New HDPE plants are also due to come onstream in 2022 in India and the Philippines.

But the elephant sitting none-too-quietly in the corner of the room is, as always, China and what its imports might end up totalling in 2022.

Our base case assumes net imports of 7.3m tonnes in 2022. This would compare with what looks likely to have been 2021 net imports of around 6.4m tonnes, based on the January-November trade data.

The ICIS base case – and, of course, you must always start with a base case for your scenario planning – assumes demand growth at 6% in 2022 and an average operating rate of 73%.

Our base case saw last year’s demand declining by 3% over 2021 with the operating rate at 86%. My personal view, as I said earlier, was that 2021 demand might have fallen by as much as 6%.

Assuming a 6% demand decline did happen last year, see my two downside scenarios for net imports this year. They also factor in lower demand growth in 2022 and higher operating rates than our base case.

The lower growth reflects the impact of Common Prosperity and Zero Covid. Higher operating rates I see as a possibility because of Dual Circulation, another group of government policies that includes reducing dependence on commodity imports in general.

Upstream refinery restructuring in China is expected to lead to more feedstocks being available to make HDPE and other petrochemicals.

“But what about the poor plant economics? If they continue won’t this cause rate cuts in China?” I can hear you asking.

Not necessarily. Our data show that between 2014 and 2021, average annual NEA naphtha-based margins ranged between a low of $162/tonne (last year) and high of $615//tonne (in 2016).

Throughout this period, however, we estimate local operating rates were at 86% per year. In other words, production did not vary in line with margins.

Around 80% of HDPE production in China is naphtha-based. The remainder includes inland plants that start with coal as the feedstock through to methanol, ethylene and then HDPE. There are a few coastal-based plants that import methanol to make ethylene and then HDPE.

I see these stable 2024-2021 operating rates as supporting my long-held view that petrochemicals production in China is as much a political or national strategic decision – about jobs and import impendence – as it is about plant economics.

China accounted for some 60% of global net HDPE imports in 2021, among the countries and regions that imported more than they exported. This explains why you need rigorous and constantly updated scenarios for China’s HDPE imports and net imports in 2022.

US HDPE production reached a record high in November last year as the industry recovered from the extensive outages caused by the Texas winter storm and hurricanes, said Chemical Data, the US-based ICIS service.

So, let’s think what this could mean for US HDPE exports in 2022.

In 2021, based on the January-November data, US exports for the full year look set to be around 2.9m tonnes, 1m tonnes less than the actual 3.9m tonnes imports reported for 2020.

It looks as if last year’s exports fell to just 31% of capacity compared with 43% in 2020. With capacity scheduled to rise by 10% this year, and assuming exports return to 43% of production, this year’s exports would rise to 4.5m tonnes.

This seems logical given that the US is structurally very long on HDPE because of heavy investments driven by highly competitive shale gas-based ethane.

ICIS also forecasts that US demand growth will fall to 3% in 2022 from 4% in 2021 as capacity increases.

Supply chain problems look set to drag on

As I said at the beginning, I see it as only a matter of time before global polyolefins markets become truly global again. The imbalances are so great that something must surely give.

Unless you’ve been living on Mars, you will know have been anything but truly global over the last 18 months. This the result of the shortages of containers and their high cost.

Other supply problems include chronic port congestion, especially at the adjacent US ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, and shortages of truck drivers. This has restricted the ability of the Asian and Middle East producers to export Asian surpluses to other regions, thereby contributing to the weak NEA margins.

Record-high price premiums for European and US material over NEA and southeast Asian mean that even when factoring in freight rates as much as seven times higher than 18 months ago, arbitrage has on paper still worked.

The problems have instead been containers not being available or the unwillingness of buyers to accept much longer delivery times.

Only a few weeks ago, hopes were reasonably high that container-freight markets would lengthen after the LNY holidays. Not now, though. Dalian has become the latest port city in China to detect Omicron following nearby Tianjin and Ningbo.

Although there had as of 20 January been no direct effects on the ports in these cities, this article in The Loadstar quoted Westbound Global Logistics as saying: “Chinese ports are being impacted by regional lockdowns, with the Omicron variant spreading. The situation varies port to port and may lead to carriers changing vessel rotations at short notice to avoid badly impacted ports.”

These rotations had become more likely over the next 2-3 weeks because of the build-up to factory closures during the LNY, added Westbound Logistics in the same article.

There has been a lot of talk about localising supply chains in response to the pandemic, but it takes years to build new factories, train all the workers and provide the logistics.

Since the pandemic, the world has become even more dependent than before on China for its imports of finished goods, said the WSJ in the same article I linked to above. This greater dependence was because Chinese factories were the first to return to normal production.

Supply chain problems are not just confined to China. Pivotal for the smooth flow of containers around the world are the adjacent US ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which are experiencing major delays.

Attempts to make the ports operate 24 hours a day are stumbling. Negotiations with workers at the ports on new employment contracts are taking place ahead of the old contracts expiring in July.

In 2015, when previous contracts expired, industrial action was only resolved when the Obama administration intervened.

Returning to China, restocking by retailers and wholesalers is expected to take place after the LNY holidays. But will the retailers and wholesalers be able to restock if Chinese workers struggle to return from the countryside to coastal manufacturing plants because of lockdowns?

Unless new restrictions are introduced, more workers are expected to travel home for the LNY holidays this year than in 2020 and 2021. This would be to compensate them for restrictions on travel during those two years.

Some logistics experts have even gone as far to suggest that supply chain disruptions are here for good. They attribute this to consolidation in the global freight industry before the pandemic.

Consolidation has left just 16 companies controlling 80% of world’s liner shipping, container production and box-leasing capacity, said this article in Freightwaves.com.

A further barrier confronting the re-globalisation of polyolefins is the renegotiation contract freight rates.

PE and PP producers, traders and buyers holding contracts for containers have benefited from much lower prices than on the spot market.

The grey area in chart below, from Freightos, illustrates the point. The low end of the grey area is closer to contract rate with, the top end more in line with spot rates, The black line shows average freight rates on the route from Asia to the east coast of North America.

The new contract rates are expected to move closer to spot rates.

I don’t buy the argument that disrupted supply chains are here for good. Further political pressure will be brought to bear on the container freight industry as government and market-driven improvements in logistics take place.

Consumption of goods moved in containers has boomed because of the pandemic. About 35% of US consumer spending was usually on durable goods but had risen to 40% since the pandemic began, according to a Bernstein report quoted in this Financial Times article.

As most of the world starts to treat coronavirus as endemic rather than as a pandemic, spending seems certain to decline on durable goods while it rises on travel and restaurants.

The less fatal Omicron variant creates the chance that this change of approach will happen at some point in 2022.

High levels of inflation always cause demand destruction. People will stop buying things because they are too expensive. There’s evidence from the US that this is already happening.

Conclusion: ICIS data will tell you when the rebalancing has begun

Consider the last chart for today, which you can see below.

If the average January 2014-Janaury 2021 premiums for NWE and US Gulf margins over NEA margins had applied over the last 12 months, the West would have been much less profitable.

Watch these margin premiums like a hawk, whether you are producer, trader or buyer. If the West started to decline towards NEA levels, this would be a sign that supply chains were returning to normal.

It is possible that the reverse might happen – the NEA increasing to Western levels – but from my 5% percentage rating, you can tell that I think this only just possible. This is because of the supply and demand fundamentals detailed above.

Recent supply chain events have led me to increase my percentage rating of the polyolefins world staying divided in 2022. Last week, my rating for the status quo was 45% out of 100, but has now risen 50%. Watch this space closely as these ratings will continue to move.

As I said, the litmus test on whether we are returning to more globalised markets will be movements in ICIS margins data – along with shifts in ICIS pricing and supply and demand data – between the different regions.

Producers need to react with new sales and operating strategies when the rebalancing begins, and traders need to be ready to cash-in on stronger inter-regional traders. Re-globalisation will result in major cost savings for buyers.

Contact me on john.richardson@icis.com for how we can support you in preparing for the return to the old normal.