By John Richardson

CONFUSED? If so, you are fully across what’s happening in the global polyethylene (PE) market. Anyone who isn’t confused is likely taking a vacation on Mars with no means of communicating with Planet Earth.

The chart below is a case in point. What you can see from the data are actual US high-density polyethylene (HDPE) exports in 2020 and 2021 versus what might happen this year.

Under Scenario 1 for 2022 exports, I assume that exports return to 43% of capacity, their level in 2020. This would lead to 2022 exports of 4.5m tonnes, up from just 2.9m tonnes last year, as local capacity is scheduled to increase by 10%.

Scenario 2 – exports at the 2021 level of just 30% of capacity – could happen if there are more extreme weather events like the Texas Winter Storm and the hurricanes that occurred last year that led to big losses in US production.

We must also consider the impact on US HDPE exports of the supply chain chaos that looks likely to continue for a good while longer.

Will there be enough trucks or railcars to get US PE to the ports? Will the West Coast ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach be hit by industrial action as the port workers’ contracts are up for renewal in June this year?

And will ports, trucking and rail transport in countries of arrival be further disrupted by the pandemic if, say, a new variant emerges that is more virulent than Omicron? UK scientists warn that this is very possible.

What about inflation and the effect on HDPE demand? Durable end-use applications, such as HDPE water and gas pipes and HDPE petrol tanks, seem vulnerable because of the effects of rising costs on real estate and auto sales.

Perhaps HDPE into packaging applications will be less affected as, of course, people will still have to eat!

Assuming US production in 2022 increases substantially over 2021 – and provided there are no logistics constraints – exports may be even higher than Scenario 2. Continued extremely high oil prices might force operating-rate cutbacks at naphtha-based crackers in Europe and Asia, creating more room for US exports.

But, again, this is on the basis that high oil prices don’t cause significant demand destruction.

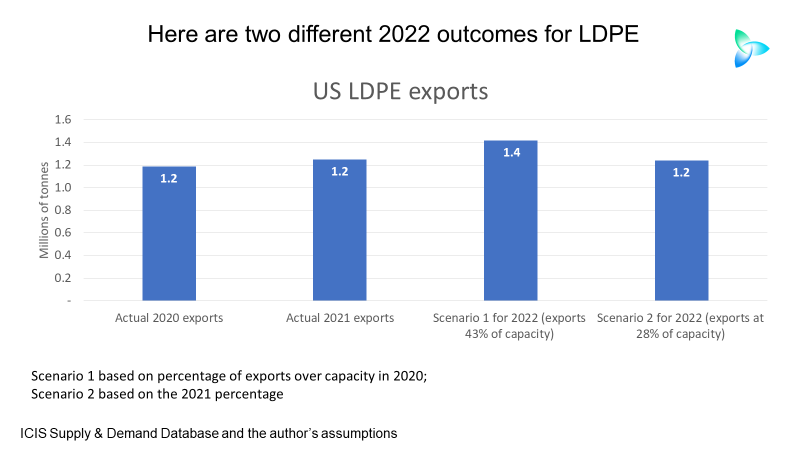

Everything I’ve said above also applies to US low-density PE (LDPE) exports in 2022. The chart below uses the same approach as in HDPE to estimate this year’s LDPE exports.

There is no new US LDPE capacity due on-stream in 2022. Note that 2021 exports were higher than in 2020 on an 18% rise in capacity. But exports as a percentage of capacity were lower.

A further complication for linear low-density PE (LLDPE), where again, of course, the same uncertainties apply, are US shortages of hexene comonomers and additives.

Chemical Data Intelligence, an ICIS service, reports that in December last year, US HDPE/LLDPE swing plants swung to more HDPE output because of the shortages. We need to try and understand how long the hexene comonomer and additives shortages are likely to last.

The chart below shows the potential huge jump in 2022 US LLDPE exports to 6.6m tonnes from last year’s 4.7m tonnes. US LLDPE capacity is scheduled to rise by 19% in 2022.

In summary, total US PE exports in 2021 were 8.9m tonnes, Under Scenarios 1 they would reach 12.5m tonnes and Scenarios 2 10m tonnes with, of course, many different outcome possible.

An extraordinary 22 months for the global PE industry

We were supposed to be in an oversupply-driven margins trough right now, but that hasn’t happened in the US and Europe, partly because of last year’s US production problems.

Margins in the West are vey strong, but northeast Asian PE margins they are are at record lows on longer supply and weaker demand.

And, as I discussed on Monday, the global pandemic has provided a lot of unexpected support for demand since it began in April 2020.

I feel it is important, while we are on the theme of confusion, to repeat 10 unknowns from Monday’s post on PE demand in the West and in China during 2022.

- A cycle out of spending on durable goods and into more services. If the pandemic becomes endemic, it seems likely there will be less demand for new computers, washing machines, automobiles, etc and more for business and foreign travel. Less PE packaging required for durable goods needs to be balanced against the extra packaging required in airport lounges, onboard aeroplanes, at business conferences and in holiday resorts.

- A winding down of government stimulus and how this would affect demand, especially PE consumption by the lower paid who are reported to have had more disposable income during the pandemic than before.

- The degree to which online spending has permanently risen because of shopping habits developed during the pandemic and greater investment in sectors such as food delivery, leading to improved convenience. Despite the sustainability pressures, a lot of PE is used in packaging internet sales.

- A switch from eating food from supermarkets to dining out. This could result in less “surface area” demand for PE (larger container sizes used by restaurants mean less corners and less lids, so, in theory, lower demand). Or maybe there will be a surge in restaurant dining as people make up for lost meals out. This may deliver a boost to PE demand.

- As offices re-open, a recovery in demand related to travelling to work and dining in nearby sandwich bars and restaurants at lunch times. But people would be spending less time in their neighbourhood sandwich bars and restaurants.

- If the coronavirus becomes endemic, there may be less PE consumption in hygiene applications – for instance, face masks as they are packaged in PE. But to what degree will precautions against infection remain mandated such as wearing face-masks? And has human behaviour become more infection-cautious?

- To what extent will higher interest rates to tackle inflation damage PE demand? OK, I might well have been wrong! Earlier this year, I had thought the strong inflationary pressures would weaken. This doesn’t look as if it will happen anytime soon.

- But if any new variant is more virulent than Omicron, this could lead to a resumption of global lockdowns, more government stimulus and declines in GDP (this may reduce inflationary pressures). Some scientists warn there are no guarantees that any new variant will be less virulent because Omicron comes from a different part of the virus’s family tree than Alpha and Delta.

- China’s Common Prosperity and Zero-Covid policies. Common Prosperity might further deflate the real-estate bubble – thereby damaging PE consumption directly and indirectly connected with property – and accelerate restrictions on single-use plastics. Zero-Covid could be good for maintaining production at China’s export-focused manufacturing plants, supporting consumption of PE that’s imported for re-export as packaging for finished goods. But the policy may negatively affect local consumer spending.

- The impact of sustainability on global demand through more restrictions on single-use plastics and redesigning of packaging to consume less PE.

Conclusion: continued support on data and analytics

US export flows matter for every region as the US exports to a wide range of destinations.

In 2021, for instance, 536,854 tonnes of US HDPE exports arrived in Asia with China accounting for the biggest amount at 166,909 tonnes. Exports to Asia represented 11% of total US exports.

Presuming that 11% of total US HDPE exports are again sent to Asia in 2022 – and that US exports reach my higher estimate for this year (Scenario 1) – this would mean 752,566.57 tonnes of US exports to Asia in 2022.

All the above data was out of date before the ink dried on this blog post. This is why, in this ever more muddled world, you need to talk to us for constantly updated data and analysis. Contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.