By John Richardson

I AM AFRAID a long pre-amble, the essential context, is necessary in today’s post on polyethylene (PE) before I get to the core point: demand could be weaker in 2022 than in 2020 and 2021, the opposite of what some PE companies predicted during the release of their Q4 results.

Or it could be stronger or the same as we saw during the two pandemic years. We remain all at sea because of the lack of adequate forecasting models.

The PE company’s arguments were centred on the notion that as the pandemic hopefully becomes endemic, leading to further recoveries in GDP growth, PE demand will move up pretty much in line with stronger GDP growth.

I see the market as being harder to predict than this including the view among some scientists that there is no guarantee that any new variant of coronavirus will be less virulent than Omicron.

Here is the pre-amble…

The dark and distant past of just 20 months ago

In the dark and distant days of April 2020 – which, given the pandemic speed of events, feels like several lifetimes ago – the polyethylene (PE) world was largely convinced that we were heading for a huge drop in demand.

The logic, which I subscribed to, seemed sound as during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and 2009, consumption fell off a cliff.

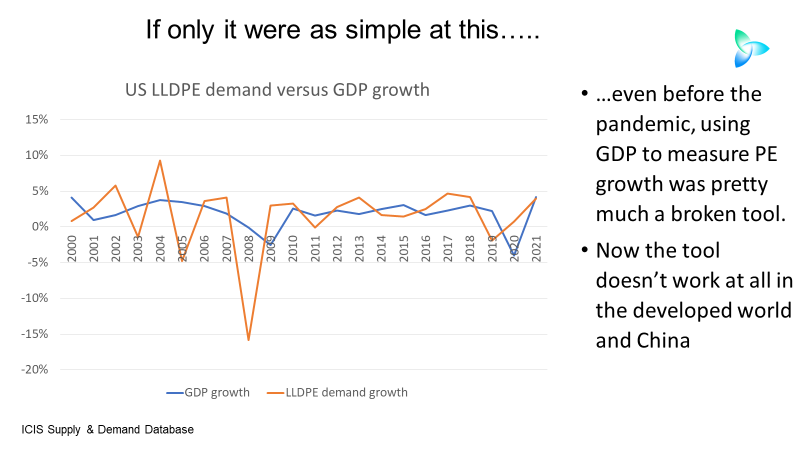

Take the US and linear-low density PE (LLDPE) as examples, where year-on-year consumption in 2008 declined by a staggering 16% with only a modest rebound to positive growth of 3% in 2009, according to the ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

Note that I will use LLDPE as an example throughout this post. But the trends are the same in high-density (HDPE) and low-density PE (LDPE).

In Europe, 2008 and 2009 demand contracted by 3% and 8% respectively. The second year of decline seems to have been the result of the impact on demand of the EU sovereign debt crisis.

China, which along with the US and Europe makes up the world’s three biggest markets, saw a 3% decline in LLDPE demand in 2008 followed by a huge 24% increase in 2009. This was the result of China launching the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus programme in response to the GFC.

So go figure, we thought. We assumed that as the collapses in GDP taking place because of the pandemic were much greater than during the GFC, consumption in 2020 – and quite possibly also in 2021 – would fall by more than during the GFC.

How wrong we were. What we did not expect was that the nature of pandemic stimulus would be different from that which occurred during the GFC.

In 2008-2009, it was all about bailing out the “too big to fail” financial institutions as the average investors in real estate bore most of the pain.

“We saw a big change in spending patterns in 2008 and 2009. Our lowest paid customers were short of money,” a friend who runs a supermarket in the UK’s midlands region told me.

“They cut back on luxury spending – fewer chocolate biscuits – and increasingly went for “super-market own brands’, in place of more expensive products made by the big brand owners,” he added.

Linking this back to PE demand, market sources say that this resulted in an overall decline in packaging demand in the US and Europe.

But this time around, stimulus was heavily targeted at the lowest paid, those who were on work furloughs or had lost their jobs in service industries affected by lockdowns.

The same supermarket manager saw a reverse trend in 2020 and 2021, with his lowest-paid customers spending more on chocolate biscuits and other luxuries because a.) they had the money and b.) they needed comfort and distraction during lockdowns.

Media reports of the same spending patterns among low-paid workers in the US appear to underline what he said.

There was also the “surface area” effect of people purchasing more from supermarkets and eating less in restaurants because of restaurant closures.

Smaller portion sizes for food bought in supermarkets meant more lids and corners – ergo, more PE demand.

The demand growth for PE in medical applications flew off the charts because of the pandemic, and PE demand seems to have benefited from the boom in consumption of durable goods.

Most of the durable goods we bought in much greater quantities were supplied by China, the 2020 “China in, China out” story of surging PE imports to wrap re-exports of exercise machines, game consoles, office furniture, rolls of carpet and tins of paints etc.

Demand was further supported by the big jump in e-commerce. Despite a big focus on sustainability, a lot of things we buy over the internet arrive wrapped in PE.

US LLDPE demand grew by 1% in 2020 despite a 4% contraction in GDP, with last year’s consumption growing by 4% as economic growth rebounded by more than 4%, according to ICIS data.

Underlining how different markets behaved during the pandemic as compared with during the GFC, US GDP contracted by just 0.1% in 2008 and yet, as mentioned earlier, LLDPE consumption collapsed by 16%.

The chart below shows US LLDPE and GDP growth from 2000 until 2021.

I will not, for the time being, blitz you with anymore numbers. So, here is just the chart for European LLDPE demand versus GDP growth, which, as you can see, follows a similar pattern to the US.

The chart below shows China’s LLDPE versus GDP growth between 2000 and 2021.

I see at as irrelevant even to talk about any correlation between LLDPE and GDP growth in China because as China’s Premier Li Keqiang was discovered by Wikileaks as saying in 2007, China’s GDP numbers were “man- made”.

Very quickly at the end of each quarter, China releases its GDP results and never revises them, despite China being such a vast and complex economy. The US instantly revises its quarterly numbers.

And you can just about guarantee that every year, China will hit its GDP growth targets.

LI added that electricity consumption, rail cargo volumes (maybe also e-commerce sales these days) and levels of lending were more reliable measures of the economy.

On lending, we can draw a good correlation between the boom in credit from 2009 onwards, the result of the huge stimulus package, and the big take-off in China’s petrochemicals demand, as China overtook Europe and North America to become the world’s biggest consumption region in most products.

Do not assume that any new variant will be less virulent

Linking growth with GDP was already a weak tool before the pandemic arrived. I believe I have demonstrated the GDP tool has become even weaker.

It seems perfectly possible that global LLDPE consumption growth might therefore fall in 2022 in the US, Europe and China relative to 2021, even if inflation and debt anxieties do not hinder recoveries in GDP as we emerge from the pandemic.

Or, as I said, consumption could be the same or even better than in 2020-2021, regardless of GDP.

I do, however, see a much stronger link between GDP and LLDPE growth in the developing world, as economic growth reflects the number of people each year who either escape extreme poverty or fall back into extreme poverty.

When you are extremely poor, you cannot afford even the most basic of modern-day goods wrapped in LLDPE.

If the pandemic does become endemic this year, then developing world demand for LLDPE should rebound pretty much in line with GDP.

But here is the thing: In 2021, ICIS estimates that the US, Europe and China together accounted for 64% of global demand versus 31% for the developing world.

The developing world comprises Africa, Asia and Pacific, including the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia, the Middle East and South and Central America.

What immediately follows obviously matters for all regions of the world.

Leading UK scientists have warned that future variants of coronavirus could be more dangerous and cause a higher number of deaths, said the UK Observer newspaper in this article.

“The Omicron variant did not come from the Delta variant. It came from a completely different part of the virus’s family tree,” Professor Mark Woolhouse, of Edinburgh University, an epidemiologist, told the newspaper.

Because we didn’t know where in the virus’s family tree a new variant was going to come from, it was impossible to say whether it would be less or more harmful than Omicron, he added.

“People seem to think there has been a linear evolution of the virus from Alpha to Beta to Delta to Omicron. But that is simply not the case. The idea that virus variants will continue to get milder is wrong,” said Professor Lawrence Young of Warwick University, a virologist.

More on this theme in later posts as I delve further into the scientific discussion and the implications for petrochemicals demand growth.

Meanwhile, let me switch my attention back to China and the developed world and provide you with a list of ten variables you need to evaluate to assess PE demand growth in 2022.

As the saying goes, “good luck with that” using existing forecasting models.

PE demand and the ten key variables to consider in 2022

- A cycle out of spending out of durable goods and into more services. If the disease becomes endemic, it seems likely there will be less demand for new computers, washing machines and automobiles etc. and more for business and foreign travel. Less packaging required for durable goods needs to be balanced against the extra packaging required in airport lounges, onboard aeroplanes, at business conferences and in holiday resorts.

- A winding down of government stimulus and how this would affect demand, especially LLDPE consumption by the lower-paid who have had more disposable income during the pandemic than before.

- The extent to which online spending has moved permanently higher because of shopping habits developed during the pandemic and greater investment in sectors such as food delivery, leading to improved convenience. Despite the sustainability pressures, a lot of PE is used to package online sales.

- A switch from eating food from supermarkets to dining out might seem more straightforward because of fall in “surface area’ demand. Not necessarily. A big surge in restaurant dining – as we catch up for lost meals out – could mean more rather than less LLDPE demand.

- If offices reopen, a recovery in demand connected with travelling to work and city centre sandwich bars and restaurants. But people would be spending less time in neighbourhood sandwich bars and restaurants. Net gains or losses for LLDPE demand? Again, nobody has a clue.

- If coronavirus becomes endemic, there may be less LLDPE consumption in hygiene applications – for instance, face masks as they are packaged in PE. But to what degree will precautions against infection remain mandated such as wearing face masks? And has human behaviour become a lot more infection-cautious?

- To what extent will higher interest rates to tackle inflation damage PE demand? OK, I might well have been wrong! Earlier this year, I had thought the strong inflationary pressures would dissipate. This doesn’t look as if it will happen anytime soon.

- BUT we may see resumption of lockdowns, government stimulus and declines in GDP that ease inflationary pressures if a new variant is more virulent than Omicron. UK scientists warn there are no guarantees of declining virulence. This could result in the strong PE growth drivers we saw in 2020-2021 remaining fully in place.

- China’s Common Prosperity and Zero-COVID policies. Common Prosperity might further deflate the real-state bubble – thereby damaging PE consumption directly and indirectly connected with property – and accelerate restrictions on single-use plastics. Zero-COVID could be good for maintaining production at China’s export-focused manufacturing plants, supporting consumption of PE that’s imported for re-export as packaging for finished goods. But the policy may negatively affect local consumer spending.

- The impact of sustainability on global demand through more restrictions on single-use plastics and redesigning of packaging to consume less LLDPE.

What historic ICIS data can tell us about the future

The other half of the 2022 LLDPE story is of course supply, as I discussed in a post last month. Substantial increases in US, China and South Korean supply are scheduled to occur this year.

The good news on supply is that this is much easier to track through ICIS trade-flow data – e.g. the size of US exports and the size of Chinese imports, along with our data and analysis of new plant start-ups and operating rates at older plants.

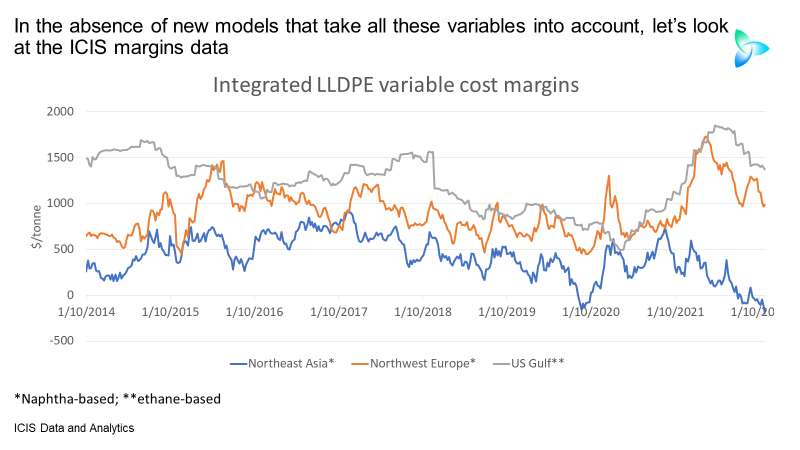

But demand is still a big black hole. As building new and highly complex models will, however, take a long time, how do we assess the health of the global PE business in the meantime? We can start with margin charts such as the one below.

Today’s discounts for NE Asia pricing versus northwest Europe and the US Gulf are at record highs. These discounts, as you can see above, are reflected in the margins.

NE Asia margins have been in negative territory since the second week of December 2021. Last week, they fell to a record low of – $ 999/tonne, [CYT(S3] with Northwest Europe margins at $988/tonne and US Gulf margins at $1,373/tonne.

European and US margins their recent record highs, but they remain extremely healthy.

I’m afraid this great divergence points to yet another LLDPE market complexity: oversupply in NE Asia that cannot be as easily relieved as in the past, because of the high cost and lack of availability of containers to move resins out of the region.

Now let’s move on to the final chart below. This illustrates what European and US margins would have been like in January 2021-February 2022, if average 2014-2020 premiums over NE Asia margins had happened.

I also compare this hypothetical scenario to what European and US margins actually were in January 2021-February 2022.

If the 2014-2020 average premiums over Northeast Asia had applied, Northwest European January 2021-February 2022 margins would have averaged $553/tonne. Instead, they were $1,251/tonne.

US Gulf margins would have averaged $875/tonne rather than their actual $1,551/tonne.

When container freight tightness eventually eases, one of two to things seem likely to happen: Either NE Asia margins will move closer to today’s levels in Europe and the US, or Europe and the US will be dragged down towards current Asian levels.

The first outcome would tell us that global demand was good without the need for sophisticated models; the second outcome would confirm that say there was something wrong.

A third outcome is possible – margin differentials staying close to where they are when container freight markets return to something like the old normal. But I feel that this unlikely because the container-freight crisis has so significantly distorted global PE trade flows.

In this highly muddled world, historical ICIS margin data offers very valuable clarity.

But we must, of course, get on with building much more sophisticated models for forecasting demand, otherwise we will keep falling back to the flawed approach of measuring growth against GDP as this is all that’s available.