LAST WEEK I challenged whether the longstanding “put option” for petrochemicals companies and investors would still apply to China 2022.

The put option rests on the well-proven notion that the worst things get in the short term, the better the immediate outlook because Beijing always rides to the rescue with big economic stimulus.

The challenge I posed to the put option was that China might only tinker around the edges of its Common Prosperity economic reforms.

The continued loss of momentum in the real estate sector – which has driven more growth in China than just about any other country in economic history – was my biggest reason for suggesting a further economic slowdown in 2022, albeit one that would be well managed.

The boom in China’s high-density polyethylene (HDPE) demand since 2009 has been driven by real estate, the data show. It is the same for other petrochemicals. Take the momentum away from the property bubble away and I said we should expect lower HDPE demand growth over the long term.

When you combined this with the restrictions on single-use plastics and China’s push to make its GDP growth less commodity intensive, I found it hard to see why we had not entered a period of more moderate growth in petrochemicals demand.

Such is the speed of events that last week feels like several years ago. History is moving at a staggering pace as always happens during major geopolitical events. We must consider the risk that China loses control of events, regardless of any amount of economic stimulus.

China imported 70% of oil and 40% of its natural gas in 2021, reported the Financial Times in this article. The cost of its crude and natural gas imports was yuan (CNY)2trn ($316bn) with a further CNY1.2trn spent on iron ore imports, said the newspaper.

Chinese wheat and corn futures prices are at record highs because of Ukraine. Heavy rains have led China’s agriculture minister to warn that this year’s domestic wheat harvest could be the worst in history. China’s wheat imports are expected to increase by at least 50% above their three-year average, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

One could argue that because of China’s big capacity for economic stimulus, it will throw so much money at the challenges that economic growth will be fine. But what if China were to confront a steep fall in its exports – something which, of course, Beijing would have limited control over?

So far so good. China’s exports increased by 16.3% in January-February 2022 on a year-on-year basis, beating analyst expectations for a 15% rise, said Reuters in this article.

Even before the Ukraine crisis, however, China faced the challenge of a slowdown in its exports of finished goods as lockdowns came to an end – the cycle out of spending on goods and into services.

Because of global inflation and further disruptions in supply chains caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, discretionary spending on durable goods seems bound to take a significant hit. Rising food and fuel costs appear likely to force many people to cut back on non-essential spending.

China was also facing its worst coronavirus outbreak in two years as 3,400 new cases were announced on Sunday 13 March, said the Guardian in this article.

“A nationwide surge in cases has seen authorities close schools in Shanghai and lock down several north-eastern cities, as almost 19 provinces battle clusters of the Omicron and Delta variants,” the newspaper added

China’s strict Zero-CPVOD policy has reportedly been relaxed slightly. We don’t know whether this is behind the latest outbreaks – although a local government official from the city of Jilin was reported by the Guardian as saying that emergency responses were not robust enough in some regions.

China might be caught in a Catch 22: If it returns to strict Zero-COVID polices, economic growth could be damaged; if it relaxes its policies growth may still be hurt.

We must consider the impact of what could be long-term shift global geopolitical landscape. Can China successfully balance its economic and geopolitical relationships with the West and Russia? Nobody, of course, knows the answer to this.

“China’s trade with Russia reached $147bn last year, according to Chinese figures, compared with $828bn and $756bn, respectively, with the EU and US,” wrote the FT in the same article already linked to above.

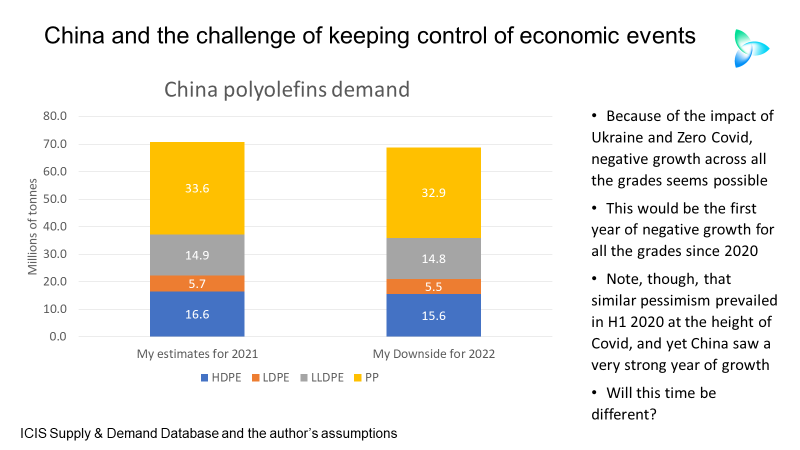

Negative growth for all polyolefins grades possible in 2022

China’s high-density polyethylene (HDPE) demand in 2021 fell by 6% with low-density PE (LDPE) consumption also 6% lower over 2021 compared with 2020, according to my estimates. But linear-low density PE (LLDPE demand increased by 1% with polypropylene (PP) consumption 5% higher.

But what if we end up with negative growth across all the grades in 2022? My downsides for China’s polyolefins demand in 2022 assume minus 6% is repeated for HDPE and LDPE. LLDPE growth is minus 1% and PP growth minus 2%. This leads to an average decline of 3%.

If this were to happen, it would be the first year since 2020 that demand for all the grades had declined on a year-on-year basis.

Similar pessimism was common in H1 2020. Polyolefins demand instead boomed over the full year because of “China in, China out” – soaring imports and local consumption to meet the big increase in exports of finished goods.

This time, as I said, might be different because of the threats to China’s export trade.

However, the West might launch another wave of major economic stimulus to counteract the effects of rising food and fuel costs. And, regardless of geopolitics, China is still the factory of the world.

Clearly, though, you need to prepare for a wide range of outcomes in a world that hasn’t felt this uncertain since the end of the Cold War.