By John Richardson

CHINA’S INCREASING self-sufficiency in high-density polyethylene (HDPE), combined with the potential for slower economic growth, is a developing story which is obviously being overshadowed by Ukraine.

But China’s decisions on operating rates – as much political as economic –- and on whether its sticks hard and fast to Common Prosperity reforms in 2022, still matter a great deal.

What might well matter even more is that if China’s fabled policymakers lose control of events because of the impact of Ukraine. Balancing essential economic reforms with compensating for the crisis in Europe looks set to be a major challenge for Beijing. The same applies to all the other grades of polyolefins, which I shall examine in later posts.

Before we return to Ukraine at the end of this post, let us analyse events in China. Consider the chart below, which shows our latest base case for China’s net imports in 2022 and my two latest downside scenarios.

Our base case sees this year’s HDPE demand growth at 7% following -4% growth in 2021, the first annual decline in China’s consumption since 2000. Operating rates are forecast to be at 80% compared with an 81% operating rate in 2020 and 93% in 2019.

My personal view is that demand might have fallen by as much as 6% last year, which is my starting point for my 2022 estimates. In Downside 1, I assume a rebound to positive growth of 5% this year.

I raise capacity utilisation to 83% on the basis that despite potentially much weaker margins on high crude oil costs (most Chinese crackers are naphtha-based), China may want local HDPE plants to run hard in order to fulfil the long-term objective of greater petrochemicals self-sufficiency.

Downside 2 involves capacity utilisation of 86% and demand growth of just 3%.

China’s net imports were at 6.2m in 2022. As the above chart illustrates, they could be either 6.1m tonnes, 4.9m tonnes or 4.1m tonnes in 2021.

Note that China’s HDPE production jumped by 38% year- on- year in January-February 2022, according to ICIS estimates. Annual capacity is forecast to rise to 20% in 2022 over last year, to 15m tonnes/year.

Before we move onto China’s economy, there’s also been some misleading talk of global HDPE markets perhaps tightening because Russia’s exports will surely decline.

But ICIS data show that amongst the world’s three four net export regions in 2022, the Russian Federation is forecast to account for just some 560,000 tonnes – 4% of the total – as the chart below illustrates.

We should also remember that US exports of PE in general should increase in 2022, provided there are no more major production issues similar to last year’s.

The slide below, from this earlier post, shows how US HDPE exports as opposed to net exports (exports minus imports) could increase to 4.5m tonnes in 2022 from last year’s 2.9m tonnes.

China’s short versus long-term economic priorities

Why what happens in China still matters so, so much relates to these two startling statistics: China was responsible for 34% of global HDPE demand in 2021 – way, way more than any other country and region – and 51% of net imports among the countries and regions that imported more than they exported.

Events in Ukraine have obviously overshadowed this year’s National People’s Congress (NPC) meeting in China, which began on 5 March and ends on 11 March. But as the above statistics remind us, we must still pay close attention to the NPC, China’s annual parliament meeting.

“China plans to set up a financial stability fund and adopt measures to keep housing prices stable, as policymakers ramp up efforts to prevent systemic risks,” wrote Singapore’s Business Times, in this article on Li Keqiang’s annual work report to the NPC.

“A fund for ensuring financial stability will be established, and market- and law-based ways will be used to defuse risks and potential dangers,” said Li, China’s premier, without providing details.

China was attempting to stem the risks from the potential financial failure of hundreds of small rural banks that were burdened with non-performing property loans, the Business Times added.

Falling home sales, which have been in decline since last July last year, were making it difficult for real- estate developers to make at least US$3.7bn in payments on dollar and onshore public bonds due in March, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

In a Reuters report on the same speech by the premier, the wire service wrote that Li pledged to “support the commercial housing market to better meet homebuyers’ legitimate needs and implement city-specific policies to promote healthy development of the property sector.”.

Policymakers would explore a new development model to accelerate the development of the rental market, Li was also quoted as saying.

Still, though, Li repeated Xi Jinping’s phrase from a 2017 speech that houses were for “living in and not for speculation”. Xi is of course China’s president. The People’s Bank of China, when announcing measures last week to stabilise the real estate market, also repeated Xi’s phrase.

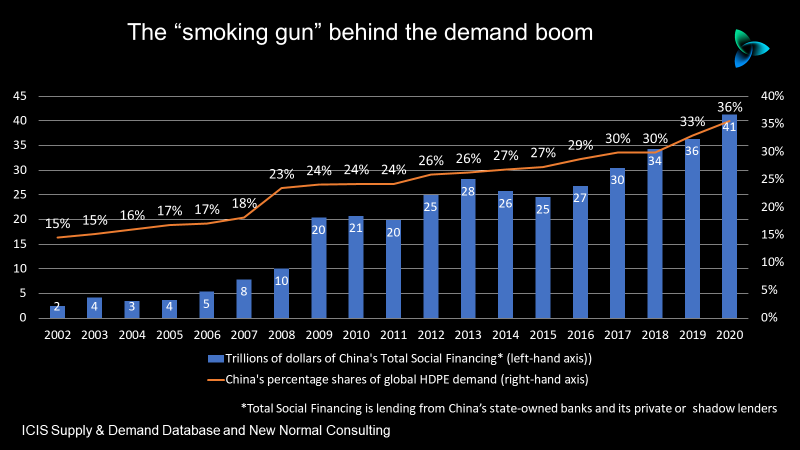

This suggests that while the Common Prosperity objective of reducing real- estate speculation is being tweaked, it is far from being scrapped. Why does this matter so much for HDPE demand in China? Re-examine the chart below, from the 5 January 2022 post.

What you can see is the rise in China’s percentage shares of global HDPE demand from 2002 up until 2020, versus the increase in Total Social Financing (TSF) – an official government measure for lending from state-owned banks and private or shadow lenders.

In 2009, whoosh, TSF doubled compared with the previous year. The cumulative impact of this credit boom saw China’s share of global HDPE demand rise from 24% in 2009 to 36% in 2020 before, as mentioned earlier, dropping to 34% in 2021.

Most of this extra lending went into the real estate sector, generating a lot of direct HDPE demand into construction and indirect consumption from conspicuous spending arising from property wealth.

The fall in China’s share of global HDPE demand in 2021, the result of the launch of the Common Prosperity policy pivot from August of that year, points to the risks ahead for consumption growth. So does the annual 4-6% decline in China’s HDPE demand in 2021, the first decline since 2000.

Now let’s look at TSF since 2002 measured against China’s HDPE demand in millions of tonnes. China’s HDPE demand increased by 222% between 2009 and 2020, from 7.3m tonnes to 17.7m tonnes.

Here is an important reminder of all three major objectives of Common Prosperity:

- Deflating the real estate bubble.

- Reducing income and wealth inequality through increasing the tax base and spending more on the poorer provinces.

- Lowering carbon emissions, cleaning up plastic waste and reducing air, soil and water pollution.

These are all potentially negative for China’s HDPE growth in 2022 as is its Zero- Covid policy – and, of course, Ukraine.

Back to Ukraine, China and the rest of the world

The China “put option” for investors is Beijing’s famous ability to smooth out economic cycles, even though some of the data China provides to the back this story up –- such as official GDP growth –- is rather questionable.

The put option rests on the idea that the worst things get in China, the better the future because this indicates a flood of new stimulus is released. But no policymaker in China or elsewhere has faced a crisis like this before.

If significant sanctions are placed on Russian oil and gas exports, the biggest threat to the global HDPE market will be lost demand from economic stagflation – the 1970s combination of low economic growth and high inflation.

Then China, along with everyone else, could well lose control of the official and real narrative as policy tools become ineffective in reversing a decline into recession. Or, of course, a multitude of other outcomes are possible as events are so incredibly volatile.