By John Richardson

ONE DAY brings hope, the next day disappointment and rising concerns about the conflict spreading –- and the next day hope arrives again. Such is the nature of the Ukraine-Russia conflict news cycle.

Late last week, for instance, hope flickered when there were reports that Russia was prepared to perhaps limit its territorial ambitions to eastern Ukraine only. But then came anxiety over President Biden’s comments in a speech to NATO allies and continued attacks on cities and towns in western Ukraine.

And as this blog post was being written, there were reports about Russia dropping some of its demands with Ukraine prepared to accept neutrality status. Peace talks were set to resume in Turkey.

On the psychological level, this is hard for all of us to deal with and infinitely harder, of course, for the millions directly caught up in this conflict.

But planning a petrochemicals business? How on earth does one respond to this daily news flow? The answer must be headline scenarios – best, – medium and worst-case scenarios.

What follows, to help you get this process going, are my three worst-case top line outcomes for the next 12 months:

- We enter stagflation – high inflation and low or even negative economic growth as developed-world governments lack the financial flexibility to spend their way out of this crisis because of rising interest rates. This happens regardless of whether the conflict is resolved or drags on. The post-conflict world still involves the West reducing its dependence on Russian energy, leading to most of the inflationary pressure being maintained.

- China, by far and away the world’s most important petrochemicals market, loses control of events for the first time in the 25 years I’ve following the Chinese economy and its petrochemicals industry. The combination of its Zero-COVID policy and rising imported energy and food costs leave it unable to stimulate its way to positive real economic growth, regardless of what the official GDP numbers say.

- The developing world (remember that this does not include China) is damaged by major food shortages and higher energy costs. This pushes many millions more people back into extreme poverty. Millions more cannot rise out of extreme poverty. Food shortages happen even if the conflict is quickly resolved because of disruptions to the next planting seasons in Ukraine and Russia, a poor wheat harvest in China resulting from heavy rains and a global fertilizer shortage.

We must also consider that developed-world petrochemicals demand was already at risk of declining in 2022 because of hopeful signs that the pandemic is becoming endemic.

New scenarios for regional and global LLDPE demand

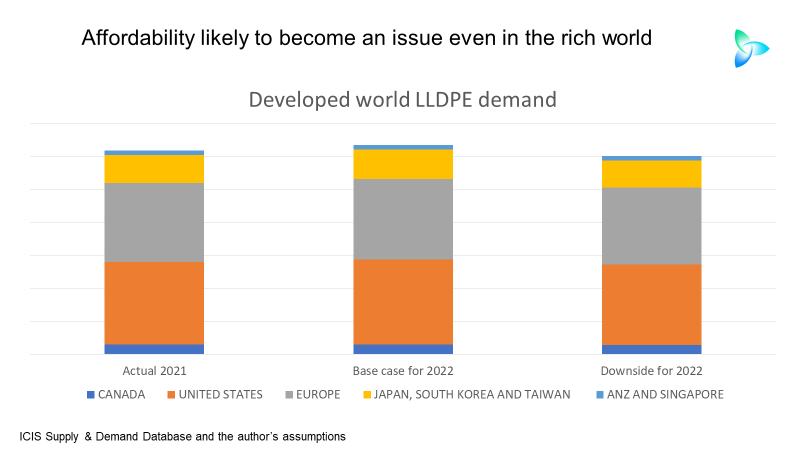

As I build towards a global picture of linear -low- density polyethylene (LLDPE) demand, let me start with the chart below, showing actual consumption in 2021 in the developed world, our base case for 2022 and my 2022 downside.

As you can see, the left-hand axis (millions of tonnes) is not available on this chart. Please contact me at john.richardson@icis.com if you want the details.

In short here, I have taken all our positive base case LLDPE growth assumptions for 2022 for the territories and regions above and turned them negative. For instance, we expect Australia, New Zealand and Singapore to grow at plus 5% in 2022. This becomes minus 5% under my downside.

Overall developed world demand declines by 3% in 2022 under my downside compared with 3% growth in our base case. Such are the inflationary pressures that even demand for basic food packaging could decline in the developed world, as I discussed in detail in my 27 March post.

In China, our base case assumes 7% year-on-year growth in demand. Very early data for 2022 (our January local production estimates and China customers net imports) instead imply full-year growth of 2%. I have therefore used 2% for my downside.

Then comes the developing world. The chart below follows my 23 March post suggesting a downside for developing-world high-density PE (HDPE) demand in 2022.

Our LLDPE base case sees strong growth in the region as it rebounds from the pandemic. For instance, we see Developing Asia and Pacific (which is minus the developed economies of Australia, New Zealand and Singapore) growing by 7%.

Under my downside, I assume all the regions of the developing world see demand contract by 3%. This would leave overall growth at minus 2% rather than our base case assumption of plus 6%.

Note that the slide also repeats the chilling warning from the head of the UN World Food Programme, which was featured in my 23 March post, about the scale of the food crisis confronting poorer countries.

Also on the slide are the six areas of analysis from the same post that you need to focus on, country by country, to get to a reasonable estimate of the impact of the food crisis on petrochemicals demand.

Today, I’ve added a seventh: – “Western relief efforts” because of this important article by Martin Wolf of the Financial Times.

While monetary policy should continue to target inflation and expectations of inflation, Wolf said that it was “possible and necessary” for fiscal resources to be applied to looking after refugees and offsetting the impact of higher food and fuel costs on the most vulnerable.

Tracking the extent to which this happens, and the effectiveness of relief efforts, needs to be another aspect of your developing-world demand analysis.

Before I move on to today’s final slide, let me give you some data on the relative importance to demand of the three regions. Under our base case assumptions, the developed world will account for 30% of global LLDPE demand in 2022, China 38% and Developing Asia and Pacific 31%.

This leaves 2% missing: The Former Soviet Union, including Ukraine and Russia. I obviously assume deeply negative growth for Ukraine and Russia compared with our base case for positive growth.

This all adds up to the chart below.

The downside would see 2022 demand falling by 2% over last year with global demand at 40.2m tonnes. This compares with our base case of plus 5% growth and 43.3m tonnes of consumption – a 3.1m tonnes difference

The downside would result in global operating rates at 79% as opposed to our base case of 84%.

Conclusion: flexibility

Please don’t think for a moment that you can shortcut the process by taking GDP forecasts and assume multiples of LLDPE growth over GDP.

“This approach hasn’t worked since the start of the pandemic and Ukraine-Russia has further added to the difficulties of measuring consumption,” said a source with a major polymer producer.

This much more detailed scenario work – where you need to evaluate and constantly re-evaluate all the macro and micro factors that are shaping today’s demand – is the key to the production and sales flexibility companies require to get through this crisis.