By John Richardson

WE NOW HAVE an agreement amongst 175 countries, reached in Nairobi in Kenya last week, to develop a legally binding treaty to deal with plastic waste.

This was something I called for last year. At the time I said we needed global limits on plastic waste that would be as important for the battle against plastic rubbish as the 2015 Paris Accords were or the struggle against global warming. I maintain this view.

My views on what the treaty should include

Two years of hard work lie ahead to hit the 2024 target of completing a treaty that I hope will contribute towards completely reshaping petrochemical cost curves.

“The agreement calls for a treaty covering the full lifecycle of plastics from production to disposal,” wrote the Guardian. Excellent news.

Equally good news is the agreement’s acknowledgement that lower-income countries “will find it harder to deal with plastic and pollution than high-income ones and so there is a need for some sort of financing model to help curb plastic use and waste,” according to the New Scientist in this article.

What must now happen is recognition amongst all the stakeholders working towards this treaty that essential single-use plastics cannot be banned – for example, polyethylene (PE) films used to wrap food and polypropylene (PP) injection grades used to make disposable syringes.

And in my view the treaty should also:

- Include economic incentives driving greater re-use – for example, incentives leading to distribution points where plastic bottles can be re-filled many times with say again shampoo.

- Encourage more R&D into reducing the volume of polymers used in packaging without sacrificing essential aspects of performance, such as extending the shelf life of food.

- Result in further R&D into how to make packaging from single rather multiple types of polymers. So called multi-layer polymer packaging makes recycling harder.

- Identify end-use applications that need to be banned because they provide no strong societal value and are hard, if not impossible, to collect and recycle.

- Most of all, ensure adequate rubbish collection systems are built for the 3bn people, mainly in the developing world, who lack such systems. An astonishing 2bn people lack any kind of rubbish collection system at all. As the old NGO example goes, a villager in Indonesia used to throw rice leaves into his local river after he had finished his lunch (rice leaves are a traditional way of wrapping food). Now he throws plastic bags into the river. Or plastic waste collects in piles on the ground and ends up being subject to uncontrolled burning to generate energy and get rid of the rubbish. This releases toxins.

Polymer producers should be held responsible by the treaty for the final disposal of the products they make – along with the converters and brand owners.

Using blockchain technology, we might be able to track each plastic pellet as it leaves a polymer plant all the way to the point where the plastic bag made from the pellet is either thrown into an Indonesian river or collected, stored in a properly managed landfills or recycled.

Companies that have invested in rubbish collection and processing systems in Indonesia should be given plastic waste tax breaks or credits they can trade.

This would, as mentioned earlier, completely reshape petrochemical cost curves. Companies far to the left of cost curves would be those who have invested in plastic waste and processing systems. Access to cheap feedstock would no longer define success.

Polymer producers should not, however, sit back and wait for the day to hopefully arrive when the treaty makes them change their behaviour.

A mountain of other legislation is being enacted right now that should be enough to motivate polymer producers to immediately press on with reshaping how they do business. The companies that don’t respond today will be tomorrow’s losers because of the ever-greater weight of legislation.

We must move quickly because of the growing evidence of the damage plastic waste is causing to the environment and human health. One area where evidence is building is the toxicity of plastic waste.

The health “of all the world’s oceans and seas” at risk

This was the warning from an October 2021 United Nations Environment Programme report. Its key findings included:

• Plastics are the largest, most harmful and most persistent fraction of marine litter, accounting for at least 85% per cent of total marine waste. They cause lethal and sub-lethal effects in whales, seals, turtles, birds and fish as well as invertebrates such as bivalves, plankton, worms and corals.

• Their effects include entanglement, starvation, drowning, laceration of internal tissues, smothering and deprivation of oxygen and light, physiological stress, and toxicological harm.

• Plastics can also alter global carbon cycling through their effect on plankton and primary production in marine, freshwater and terrestrial systems. Marine ecosystems, especially mangroves, seagrasses, corals and salt marshes, play a major role in sequestering carbon.

• The more damage we do to oceans and coastal areas, the harder it is for these ecosystems to both offset and remain resilient to climate change.

• When plastics break down in the marine environment, they transfer microplastics, synthetic and cellulosic microfibres, toxic chemicals, metals and micropollutants into waters and sediments and eventually into marine food chains.

• Microplastics act as vectors for pathogenic organisms harmful to humans, fish and aquaculture stocks. When microplastics are ingested, they can cause changes in gene and protein expression, inflammation, disruption of feeding behaviour, decreases in growth, changes in brain development, and reduced filtration and respiration rates.

• They can alter the reproductive success and survival of marine organisms and compromise the ability of keystone species and ecological “engineers” to build reefs or bioturbated sediments.

• Risks to human health and well-being arise from the open burning of plastic waste, ingestion of seafood contaminated with plastics, exposure to pathogenic bacteria transported on plastics, and leaching out of substances of concern to coastal waters.

• The release of chemicals associated with plastics through leaching into the marine environment is receiving increasing attention, as some of these chemicals are substances of concern or have endocrine disrupting properties.

• Microplastics can enter the human body through inhalation and absorption via the skin and accumulate in organs including the placenta. Human uptake of microplastics via seafood is likely to pose serious threats to coastal and indigenous communities where marine species are the main source of food.

• The links between exposure to chemicals associated with plastics in the marine environment and human health are unclear. However, some of these chemicals are associated with serious health impacts, especially in women.

• Marine plastics have a widespread effect on society and human well-being. They may deter people from visiting beaches and shorelines and enjoying the benefits of physical activity, social interaction, and general improvement of both physical and mental health.

• Mental health may be affected by the knowledge that charismatic marine animals such as sea turtles, whales, dolphins and many seabirds are at risk. These animals have cultural importance for some communities. Images and descriptions of whales and seabirds with their stomachs full of plastic fragments, which are prevalent in mainstream media, can provoke strong emotional impacts.

Grim reading, eh? I recommend reading the rest of the report and this report, released last month, by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

“Only 9% of plastic waste is recycled (15% is collected for recycling but 40% of that is disposed of as residues),” said the OECD study.

“Another 19% is incinerated, 50% ends up in landfill and 22% evades waste management systems and goes into uncontrolled dumpsites, is burned in open pits or ends up in terrestrial or aquatic environments, especially in poorer countries”, the study added.

New methodologies for forecasting polymers demand are needed

I’ve written before that if polymers demand in the developing world continues to grow very rapidly it would be a sign of progress in the battle against extreme poverty, as polymers improve the quality and length of human lives. They are essential for modern-day healthcare and for food supply chains that make sure people don’t go hungry.

But how rapidly? Conventional forecasts assume that as the region’s GDP growth will remain strong, so will the expansion in demand for polymers. But what if GDP growth becomes less polymer intensive as some unnecessary single-use plastic applications are banned, as more bottles are re-used and as less volumes of polymers are needed to make packaging?

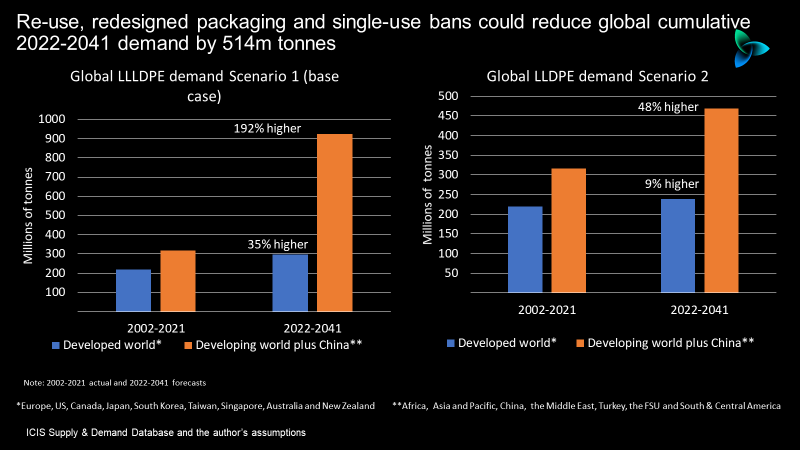

This thinking led to the charts at the beginning of this post. The chart on the left shows the ICIS base case for global linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) demand growth in the 20 years from 2022 until 2041 versus actual consumption in 2002-2021.

We assume growth of no less than 192% in 2022-2041 in the developing world plus China (China falls somewhere between being a developed and developing economy) and 35% in the developed world.

Just for argument’s sake – and there no basis for this other than guesswork – my downside scenario reduces 2021-2041 to a quarter of these levels. Developing world demand rises by around 48% and developed world demand increases by 9%.

The result is cumulative global LLDPE demand would be a staggering 514m tonnes lower under my downside than under our base case.

You must built proper forecast methodologies that consider the transition to less polymer intensive GDP growth – or polymers growth that is less linked to GDP than in the past. This is what we are doing at ICIS.

Conclusion: Geopolitics and recycling

Let’s hope that the geopolitical turmoil in Ukraine doesn’t delay more legislation to deal with the plastic waste crisis and the work needed to achieve a global treaty in 2024. But the turmoil, as I discussed on Friday, could accelerate the adoption of one of the solutions to plastic waste – recycling.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has highlighted the risks of being heavily dependent on energy and polymer imports from any country. Recycling is a “local-for-local” manufacturing chain because you cannot move plastic waste long distances for sustainability and economic reasons.

Despite all the immediate challenges petrochemical companies face resulting from Ukraine, I believe they must press on with reducing carbon emissions and plastic waste – two very separate challenges. I can see absolutely no downsides in doing so.