By John Richardson

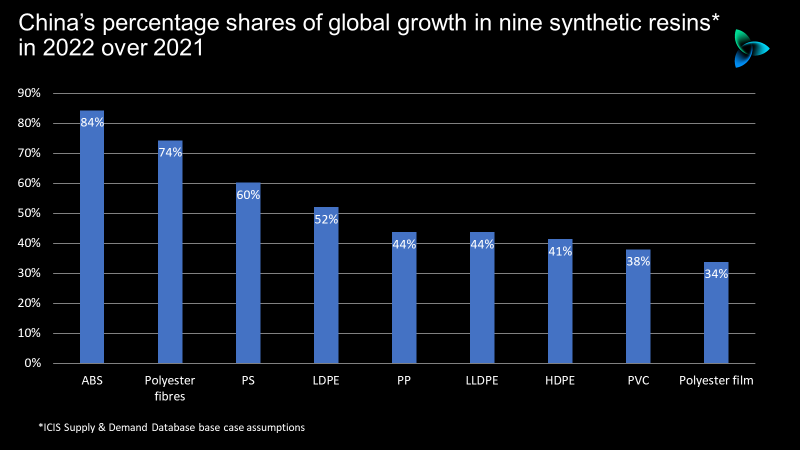

THE ABOVE CHART is the type of chart that, if I’d seen it eight years ago, I would’ve said, “No, that’s impossible, I cannot believe that China can be such a big driver of the global industry,” when I first started studying our excellent ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

(The chart shows China’s expected complete dominance of global demand growth in nine synthetic resins in 2022 over 2021).

But when I checked earlier charts of this nature with my contacts, they said words to this effect: “Yes, of course. Didn’t you know? Wake up and smell the coffee”.

I awoke to the realisation that China was by far and away the most important driver of global petrochemicals and polymers growth, actual demand – and imports across all the major products.

Here is our base case chart for 2022, showing China’s percentage shares of global demand for the same nine synthetic resins.

It is important to note that the high percentages in the above chart do not only represent “local-for-local” consumption. For instance, China’s 1.4bn people don’t consume 74% of the world’s apparel and non-apparel products made from polyester fibre.

China’s vast export-focused manufacturing industries instead drive much of China’s demand for polyester fibres and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) – e.g. exports of blouses, shirts and washing machines.

The chances of recovery in 2022 seem to be diminishing by the day

For the first time in the 25 years that I’ve been following China’s economy, it seems the country is in recession when you examine the real-time economic data rather than the questionable official GDP numbers.

The chances of China recovering from recession later this year seem to be diminishing almost by the day, as it becomes more apparent that relaxation of the zero-COVID policies isn’t going to happen anytime soon.

The UK’s Guardian newspaper reported on 7 May: “Xi Jinping has confirmed there is no intention to turn away from China’s zero-COVID commitment, in a major speech to the country’s senior officials that also warned against any criticism or doubting of the policy.

“Addressing the seven-member politburo standing committee, China’s highest decision-making body, specifically about the Shanghai outbreak, the president said China’s response was ‘scientific and effective’”. He told officials to ‘“unswervingly adhere to the general policy of dynamic zero-COVID’. “

President Xi’s recent comments appear to underline the view that the zero-COVID policies won’t be relaxed until after an important political meeting in November, when the president is expected to be given a third term in office.

And on Wednesday 11 May, a peer-reviewed study by Shanghai’s Fudan University was published in the Nature journal.

The study said that a decision by Chinese authorities to lift Zero-COVID measures could see more than 112m symptomatic cases of coronavirus, 5m hospitalisations, and 1.55m deaths.

“We find that the level of immunity induced by the March 2022 vaccination campaign would be insufficient to prevent an Omicron wave that would result in exceeding critical care capacity with a projected intensive care unit peak demand of 15.6 times the existing capacity,” the authors wrote.

The study, however, did say that with access to vaccines and antivirals and “maintaining implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions”, authorities could prevent the health system being overwhelmed. It suggested these factors could be more of a focus in future policies.

But implementing changes in policies would likely take considerable time, as it might involve importing foreign vaccines that are said to be more effective than Chinese versions and raising low vaccination rates among the elderly. China’s vaccination programme has slowed down because of the lockdowns.

China’s polymers growth could be minus 6m tonnes in 2022 rather than plus 7m tonnes

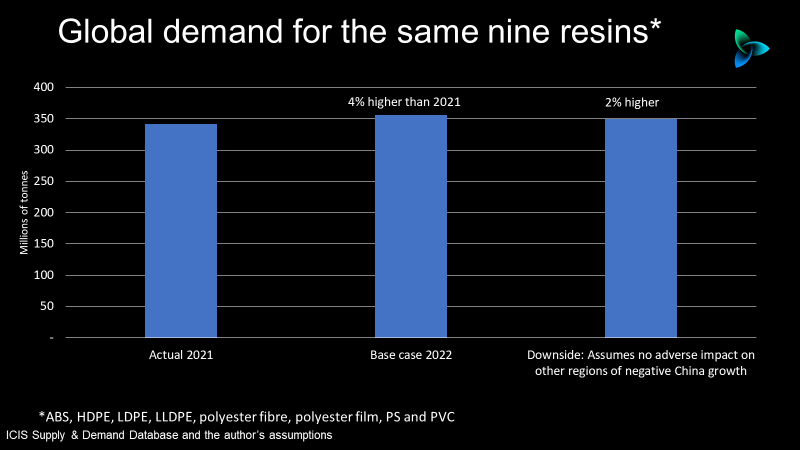

There is a realistic possibility that polymers growth in China will turn negative in 2022 over last year. The chart below shows actual demand for the same nine polymers in 2021, our base cases for this year and my downsides.

Instead of demand for the nine polymers growing by 7m tonnes in 2022 under our base cases, my downsides see consumption falling by 6m tonnes.

And here are our base case assumptions for 2022 growth versus my downsides for the nine resins in percentages.

My downsides for high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density PE (LDPE), linear low-density PE (LLDPE) and polypropylene (PP) percentage growth are based on my most –recent worse-case scenarios.

ABS, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyester fibres see the biggest declines on two assumptions:

- China’s exports, containing ABS and polyester fibres, slow on zero-COVID-related logistics problems and the cost-of-living crisis in the West.

- The lockdowns severely limit domestic construction activity. Construction is the main driver of PVC demand.

The falls in demand for polystyrene (PP) and polyester film are in line with what occurred in 2008 over 2007, during the Global Financial Crisis

Now let me put our base cases for Chinese growth and my downsides in the global context.

The downsides assume that, while China’s growth turns negative, demand for the resins in the rest of the world would grow in line with our base cases. But this seems highly unlikely because of the global impact of a weaker-than-expected Chinese economy.

Even under the unlikely assumption that the rest of the world would be unaffected by a China economic recession, my China downsides would lead to 2% global growth for the nine resins in 2022 compared with our base case of 4%.

Normal economic activity is very difficult

The data in today’s post reminds us of just how lopsided our industry is, how we have become far too dependent on just one country. This seemed fine in the world before the Ukraine-Russia conflict and this year’s zero-COVID policies, but maybe not now.

Perhaps my downsides are too pessimistic, though. Other more positive scenarios are clearly necessary for adequate business planning as it is possible that the zero-COVID policies end sooner than I am assuming.

Gradual easing of restrictions over the next few months might happen, leading to a partial recovery in consumer demand and industrial production.

But it does seem logical, based on today’s conditions on the ground, that growth in China will at the very least be weaker than had been expected.

How can it not be given that some 340m Chinese citizens are subject to some degree of lockdowns? Most of these people live in the richer provinces that drive the bulk of China’s economic growth.

It is worth noting that the zero-COVID restrictions are making normal economic activity very difficult. Some factories remain closed and the rules governing delivery drivers are making delivery of internet sales very challenging.

This is the opposite of what occurred in the West at the height of the pandemic when internet sales boomed – a major reason for strong polymers demand growth.

And until China’s factories fully get back to work and until zero-COVID logistics problems ease, there is little chance of a recovery in Chinese exports, which are in important driver of the country’s petrochemicals demand and imports.

Even when China’s manufacturing and logistic are back to normal, we need to consider the impact of the West’s cost-of-living crisis on the country’s export sales.

This already appears to be having an effect, according to Trade Data Monitor, which wrote in its latest report on China’s trade flows: “In April, exports rose only 3.9% over the previous year, to $273.6bn. That’s the lowest rate in two years, and far below a 14.7% improvement in March.

“Much of the economic analysis has focused on the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the pandemic locking down ports in China, but the bigger picture is that the world is now having to adjust to consumers no longer having huge stacks of free cash in their pockets to spend on retail goods made in China.”

These are very difficult times, I am afraid, as regards China’s demand. There is no getting away from it.