By John Richardson

WAY BACK IN 2014 I first highlighted the risks involved in China’s local governments selling land to raise money for their public spending. It is estimated that around 85% of China’s central and local government spending is by of local governments.

This approach worked very well while land prices kept on rising. But since China launched its Common Prosperity pivot last August, land and real-estate sales have weakened.

The zero-COVID lockdowns have taken further air out of the property bubble, as travel restrictions have added to the downward sales momentum.

“In April and May [2022], new home prices fell in more than half of China’s 70 biggest cities for the first time since 2016, and sales of such properties tumbled nearly 60%,” wrote the New York Times in a 20 June article.

Efforts to boost the economy through more infrastructure spending were being stalled by a shortfall in local government finances caused by the deflated real-estate sector, reported the South China Morning Post.

An inspection by China’s audit office found that 10 regions used the yuan (CNY) 13.7bn ($3bn) they raised from selling special purpose bonds, which were meant to be mainly spent on infrastructure, to pay wages and meet operating costs, said the newspaper on 22 June. audit inspection found that 28 provinces misused 1.4 billion yuan, including for repaying debt.

The audit inspection reportedly found that 28 provinces used Yuan1.4bn raised from the bonds for purposes other infrastructure projects, including paying-down debts. Special purpose bonds are bonds that the central government allows local authorities to issue, specifically to spend money on infrastructure.

Unless the property market is revived, we might therefore see a limited increase in infrastructure spending during the remainder of 2022.

Given the stop-start nature of relaxing zero-COVID polices and the negative impact this is having on China’s retail sales, boosting infrastructure spending might be the only way to revive the economy.

But even if infrastructure spending can be revived, it may not deliver the kind of economic rebound we have seen in the past, according to François Godement, Institut Montaigne’s Senior Advisor for Asia.

“Investment, especially into infrastructure, is the engine that pulls through the economy. Even with this remaining engine, there is one big reservation: so many roads, rail lines, ports, airports, cities, energy plants and model cities have been built that they barely leave room for more,” wrote Godement in a June 2022 research paper.

All the above helped to explain why iron ore prices, so vital for the Australian economy, had fallen by 20% during the previous three weeks, wrote Karen Maley in a 28 June Australian Financial Review article.

The above could also help us understand what is happening in another commodity raw material market – high-density polyethylene (HDPE).

The best outcome may now be flat HDPE demand growth

My previous best-case outcome for China’s HDPE demand growth in 2022 was 6%. My worst-case scenario was a 3% decline. Now, though, I worry that the best-case outcome for 2022 HDPE demand could be flat or zero growth. My worst-case outcome is a 4% decline (see the slide below).

But despite the stop-start nature of relaxing lockdown, restrictions have mainly been less severe since the start of June.

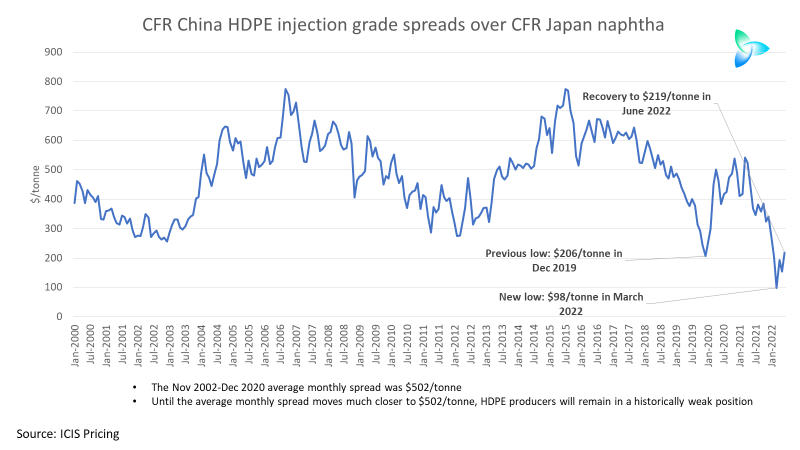

Let’s therefore look at what the spread data for June is telling us. This is the spread or gap between prices per tonne of HDPE and costs per tonne of naphtha feedstock.

As I discussed in my LinkedIn post on 27 June, the latest spreads data for average CFR (cost & freight) China PE and polypropylene (PP) prices versus CFR Japan naphtha costs suggest not much of a recovery.

Focusing just on HDPE injection grade prices (it is the same pattern in the other grades of HDPE) versus naphtha, the chart below shows the market moved in the right direction in June.

In March 2022, the China HDPE spread fell to just $98/tonne – by far the lowest since our price assessments began in January 2000. The previous monthly low was $206/tonne in December 2019 – a full 110% higher.

I expected that spreads would bounce-off such an extraordinary low, which happened in April and May.

I was less convinced that the pattern would continue in June. But, as you can see from the chart, the June spread rose to $219/tonne from $155/tonne in April. And the June spread was above the earlier record low of $206/tonne in December 2019.

But consider the following:

- The November 2002-December 2020 average monthly spread was $502/tonne (in 2021, the average monthly spread was $405/tonne).

- Until the average monthly spread moves much closer to $502/tonne, HDPE producers will remain in a historically weak position.

As always, the economic views in the first section of this post represent just one perspective. And time and again, China has proved the sceptics wrong by achieving recoveries from brief economic downturns.

But long-term spreads data for chemicals and polymers in general are free of opinions – they are, of course, just the numbers. Spreads data are just about as close as we can get to an objective view of what is really happening, on the ground, in any economy.

Let’s also put China’s HDPE spreads into the long-term context of oil prices. The chart below shows that in previous run-ups in crude prices and so naphtha costs, HDPE producers have been better able to pass cost increases on to converters.

China’s HDPE imports in 2022 could be as much as 1.6m tonnes lower than last year

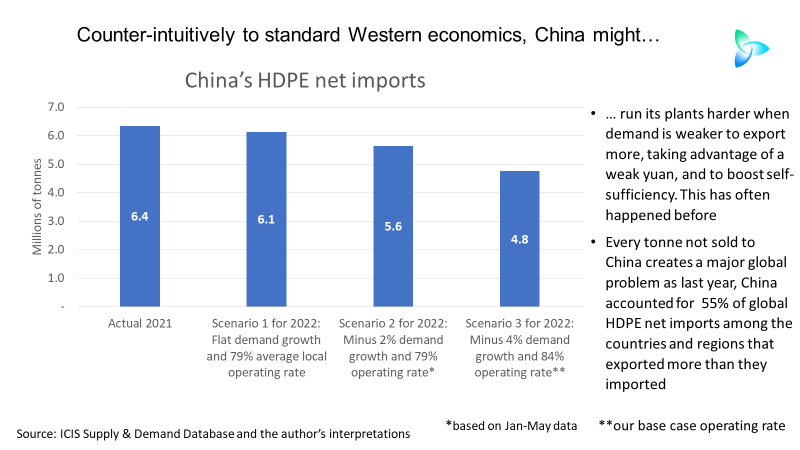

In 2021, China accounted for more than 30% of global HDPE demand, up from approximately 12% in 2000.

Interestingly, though, China’s share of global net HDPE imports edged down between 2000 and 2021. This was among the countries and regions that imported more than they exported.

In 2000, China’s net imports were 59% of the global total versus 55% in 2021, according to the ICIS Supply & Demand Database. This makes today’s final chart very important.

The chart presents three different scenarios for China’s HDPE net imports in 2022 versus what happened last year.

Scenario 1 year involves flat demand growth and an average local operating rate of 79%. The operating rate reflects what we estimate was local production in January-May 2022.

Under this scenario, 2022 net imports would total 6.1m tonnes versus 6.4m tonnes in 2021.

Scenario 2 sticks to the 79% operating rate but demand growth falls to minus 2%. This is based on the January-May data. Net imports would fall to 5.6m tonnes.

Scenario 3 involves an operating rate of 84% and minus 4% demand growth. This would lead to imports of just 4.8m tonnes. The 84% operating rate is what we assume in ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

Standard Western economics involves reducing operating rates in a weak demand environment, but this has often not been the case in China.

China may again choose to run its plants hard to boost export earnings. A weaker yuan versus the dollar could support this decision. So far this year, the yuan has weakened against the dollar.

Conclusion: one set of views only

As always, this post represents just one set of views – obviously, mine – and my interpretations of the data. And to stress again, my scenario work is for demonstration purposes only.

For proper scenario work, contact me and I can put you in touch with our excellent team of analysts, including our team in China