By John Richardson

THE NOISE is deafening, making it very difficult to work out what is really happening in the world’s most important petrochemicals and polymers market.

Politics, the unreliability of some macroeconomic data and all our individual confirmation biases make understanding China even harder than usual in 2022. As we all know, China is never easy to fathom.

Luckily, though, we have the ICIS data that clearly tell us China’s economy is in a deep trough, meaning, of course, weaker-than-expected petrochemicals demand growth. Until or unless the data start correcting towards long-term averages, we know that the trough will continue. It is as simple as this.

Weak demand is occurring at a time when China is raising self-sufficiency in several major petrochemicals and polymers, and when big new capacities have been brought on-stream or are close to being commissioned in South Korea, Malaysia, Vietnam and the US.

The importance of spreads data

Spread analysis – studying the differentials between prices per tonne for a product and costs per tonne of raw materials – has always been a good measure of supply and demand balances. Spreads also serve as a rough guide to profitability.

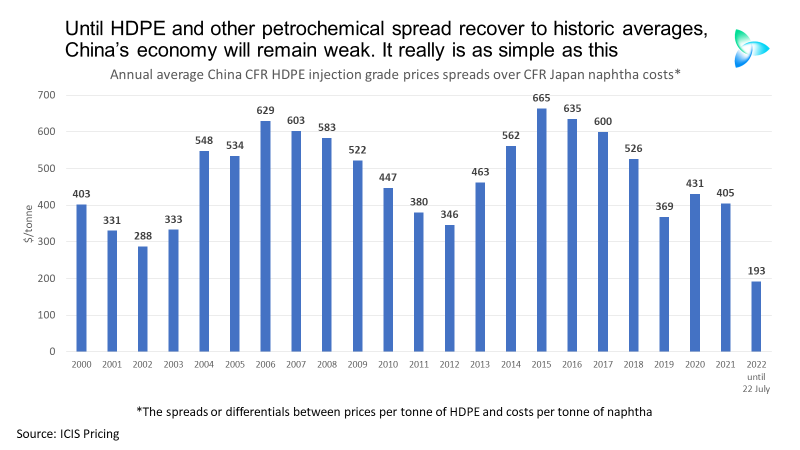

Let us look at what this year’s spreads data is telling us in just one polymer – high-density polyethylene (HDPE). This is an updated version of the chart I published last week. This latest chart includes naphtha costs and HDPE prices during the week ending 22 July 2022.

The updated chart below shows monthly spreads between ICIS CFR (cost & freight) HDPE injection grade prices in China and our assessments of CFR Japan naphtha costs. The chart runs from January 2000, when our assessments began, up until 22 July 2022.

In December 2019, the spread fell to $206/tonne, which at the time was the lowest since 2000, on a big build-up in new capacity. Linear low-density (LLDPE) and polypropylene (PP) spreads also fell to record lows during the same month.

Shortly afterwards, of course, the pandemic arrived, resulting in a dip and then a surge in spreads as China enjoyed an export-led recovery.

China’s exports surged in H2 2020 as it supplied most of the goods the rich world bought during lockdowns – computers, game consoles, white goods, etc. This trade boosted China’s petrochemicals demand and its imports. Global markets tightened.

But look at what has happened since March 2022. During that month, as oil prices surged on the Ukraine-Russia conflict Chinese demand began to weaken because of domestic lockdowns and other restrictions introduced under the zero-COVID policies.

The March 2022 spread declined to just $98/tonne. Spreads have since recovered but remain historically low. In July, up until the week ending 22 July, the spread was $219/tonne.

The pattern you see in the above chart is the same in several other products.

The next chart puts the whole of 2022 into the context of each of the years from 2000 until 2021. The average HDPE spread in January-July 2022, again up until 22 July 2022, was just $193/tonne, easily the lowest since 2000.

You may argue that the very weak spreads since March this year, which has dragged down the 2022 average, are mainly the result of rapidly increasing oil prices and therefore naphtha costs. But spreads in other regions have been a lot stronger since March. But consider the chart below.

This chart shows actual costs for naphtha and actual HDPE prices rather than the differentials. During previous rapid run-ups in oil prices, as you can see, HDPE producers were much better able to pass on higher costs to converters through raising HDPE prices.

Between 2003 and the Global Financial Crisis that began in September 2008, HDPE prices rose steadily as naphtha costs increased.

We can see the same pattern of effective cost pass-throughs from 2009 until the commodity-price collapse of late 2014, and from the China-led recovery in H2 2020 up until this year. In contrast, look at the narrow gap between the blue and red lines so far this year.

China’s HDPE demand and net imports

Now let us look at what the latest ICIS data say about HDPE demand in China.

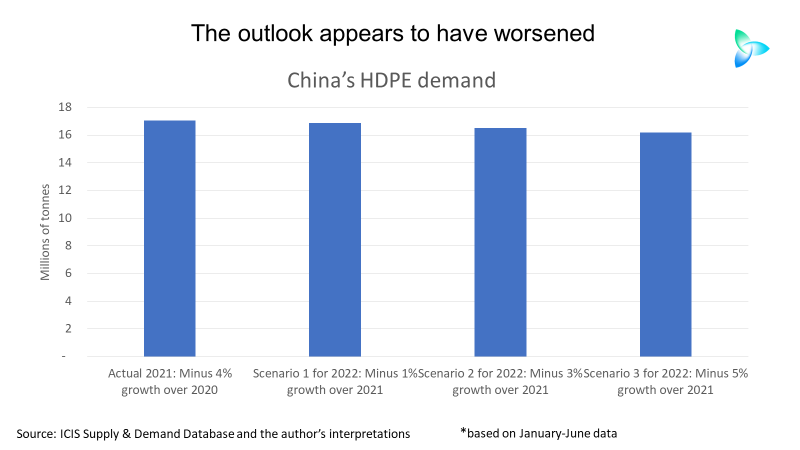

The ICIS estimate for local production in January-May 2022 and the China Customs net import number, when annualised (divided by five and multiplied by 12), suggested full-year 2022 demand growth of minus 2%.

But the January-June numbers point towards minus 3% (Scenario 2 in the chart). The outlook for the full year has been worsening month on month since March.

The chart also includes two other scenarios for China’s HDPE consumption in 2022.

To be consistent with my month-by-month estimates since February, Scenario 2 is the medium-case scenario. Scenario 1, the best-case outcome, is two percentage points higher than the medium-case outcome; Scenario 3, the worst-case result, is two percentage points lower.

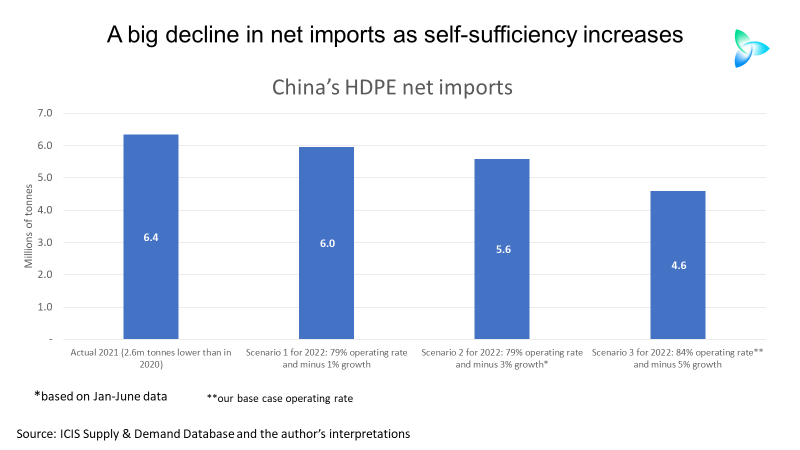

The chart below provides three different outcomes for China’s HDPE net imports (imports minus exports) in 2022.

Based again on annualising the January-June China Customs department number for HDPE net imports, full-year net imports look as if they will be 5.6m tonnes (Scenario 2 in the above chart). This is unchanged from January-May.

But 5.6m tonnes would compare with 6.4m tonnes of net imports in 2021 and close to 9m tonnes of net imports in 2020. China is scheduled to raise its HDPE capacity by 22% in 2022 to 13.8m tonnes in a weak growth environment. This would follow capacity increases of 14% in 2020 and 18% in 2021.

The ICIS estimate for local production in January-June suggests a full-year operating rate of 79% compared with our earlier expectation of 84%.

Deep production cutbacks have taken place in China since March in several petrochemicals. This is the result of weak demand and poor profitability, evidence of which we can see in the weak spreads. We might therefore also see delays to the start-up of some new plants in 2022.

But there is another outcome. China could decide to bring its new capacity on-stream on schedule and run its plants at a higher operating rate in H2 than in H1. Local producers might raise exports, taking advantage of what could remain a weak yuan versus the US dollar, while lowering the need for imports.

This outcome is represented by Scenario 3 in the above chart – an average annual operating rate of 84% and demand growth at minus 5%. This would result in net imports of just 4.6m tonnes in 2022.

Each tonne not sold to China creates a major global problem as last year, China accounted for 55% of global HDPE net imports among the countries and regions that exported more than they imported, according to the ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

Conclusion: follow the data

I could have written a different post today, involving a detailed focus on the reasons why zero-COVID policies would continue leading to more lockdowns, mass testing and other measures that damage economic growth.

I could have added to the gloom by concluding that China’s economic recovery would remain stop/start until or unless it developed its own effective mRNA vaccine. Lack of a local version of an mRNA vaccine is said to be a major reason for the zero-COVID policies.

But even if or when such a vaccine becomes available, Nature magazine warned in a 27 June article: “A highly effective mRNA vaccine would reduce the chances of widespread serious infections that could overwhelm hospitals. However, it is unlikely to bring an end to the country’s strict zero-COVID strategy, which uses mass testing and lockdowns to quash all infections.”

I might have also gone into detail about the implications of the inverted China interest-rate yield curve reported by the Financial Times in this 25 July article.

“Some of China’s largest banks are offering a lower interest rate on long-term deposits compared with short-term as a dearth of quality lending opportunities points to a sustained slowdown in the engine of global economic growth,” wrote the newspaper.

Normally, interest rates on longer-term deposits must be higher than short-term deposits in order to attract savers.

I see the inverted yield as a sign that the zero-COVID policies are combining with economic reforms under the Common Prosperity programme. I therefore see weaker-than-expected growth over at least the next three years.

But this is obviously just an opinion, of course. To discover whether I am right, follow the ICIS data. If there is no sustained return in spreads to historic averages over the next three years, I will have been correct; a recovery will demonstrate that I was mistaken.

Again, it really is as simple as this. This makes ICIS petrochemicals data, when interpreted correctly, commercial gold dust.