By John Richardson

A BIG QUESTION, immediately after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, was whether Europe would be able to maintain essential production of polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) because of energy-supply reductions. This led to speculation that Europe might have to import more polyolefins to ensure sufficient supplies of plastic films and bottles for medical and food-supply chains.

The chart below shows European dependence on Russian gas compared with country-by-country percentages of the region’s total PE capacity, Germany is the standout risk country as it has a nearly 50% reliance on Russia for its gas supplies with a total of more than 70% of Europe’s PE capacities across the three grades. In the case of the Netherlands, it is the location for just under 40% of capacities with its dependence on Russian gas at around 20%.

As you can see below, PP capacities are more evenly distributed across Europe. Germany accounts for some 20% of PP capacities with the Netherlands accounting for just under 10%.

Many thanks to Yashas Mudumbai, an ICIS Data Reporter, for preparing these charts.

But while, as I said, speculation over European production cutbacks occurred during the early days of the crisis, it was recognised that a far as durable end-use applications went, the dent in European demand was a bigger issue. PP is of course more vulnerable that PE, as a higher proportion of PP consumption goes into end-use markets such as automotives and white goods.

Energy costs could be a bigger issue than supply

The risk of supply production cutbacks forced on European producers by energy cutbacks certainly hasn’t gone away. But, as the Financial Times wrote in a 10 September article: “Confidence is growing in European capitals that Europe can get through the winter without severe economic and social dislocation or energy rationing. Von der Leyen said the EU had ‘weakened the grip that Russia had on our economy and our continent’.”

The newspaper added that gas storage in the EU was at 82%, well in advance of the 80% target the bloc set for the end of October. Member states had diversified supplies through increase pipeline imports from Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan and LNG from the US and other producers. Nuclear, coal and renewables power generation is also being cranked up in order to hedge against the very real risk that Russia stops all gas supplies to Europe during the winter.

Russia could afford to do this, according to an 11 July Economist article. While the magazine said that oil exports had been worth 10% of Russian GDP over the previous five years (hence, all the efforts to maintain crude exports), gas exports were worth just 2% of GP over the same period.

Gas storage today doesn’t obviously equal to what levels might be in, say, February, in the depths of a very cold European winter. And for Europe’s polyolefins industry, the energy challenge isn’t just the gas-fired electricity they draw from the grid, but also the large amounts of natural gas needed to heat upstream refineries and steam cracker furnaces.

Even if, though, the supply of gas isn’t an issue this winter, the costs of gas and all other types of types of energy could force polyolefin producers to cut output because of weak margins. Because European gas has become the marginal supply source, nuclear, coal and renewable energy is being priced off gas, creating a profits bonanza for suppliers of other types of energy – and a huge increase in overall energy costs.

The Economist wrote in an 8 September article that European gas prices stood at the “equivalent of around $400 for a barrel of oil. At today’s futures prices, annual spending on electricity and gas by consumers and firms across the European Union could rise to a staggering €1.4trn, up from €200bn in recent years, reckons Morgan Stanley, a bank.”

With the benefit of hindsight, Germany wasn’t wise to allow itself to become nearly 50% dependent on Russian gas supplies. And, as I said, the country’s chemicals industry faces the “double whammy” of needing lots of Russian gas to fire its furnaces, as well as of coursed drawing power from the grid. When you look at the above PE chart again, it tells us that more than 70% of European PE revenues are highly exposed to gas shortages and surging overall energy costs, as Germany is the location for more than 70% of European PE capacity.

Another reason why we could see European polyolefins production cuts is the impact of surging energy costs on end-user demand.

“Market players in Europe usually expect to return from summer breaks with something of a spring in their step. The quietest days of August give way to a busier September and often a relatively strong fourth quarter. This year is different on many levels,” wrote Nigel Davis in this 5 September ICIS Insight article.

He added that extremely high energy costs and fears over energy security had resulted in great caution among chemicals and polymers buyers. Operating rates throughout manufacturing supply chains had fallen – petrochemicals included – and inventories had built as inflation and the economic downturn took its toll.

The traditional post-holiday pricing bounce in the polyolefins value chain didn’t happen. In fact, instead PE and PP prices fell last week as the monomer contracts for September settled much lower than in August. The ethylene contract settled at settled at €1,305/tonne, down by €120/tonne from August. September propylene settled at €799/tonne, €165/tonne lower than in August.

It is hard to see why sentiment would consistently improve over the next few months given the uncertainties created by the energy crisis. Converters will surely be mindful, before they restock resins, that they too might have to shut down because of lack of energy, as they also constantly gauge the impact of the cost-of-living crisis on their end-use markets.

Sure, large sums of money have already been pledged to help low-paid workers and pensioners meet soaring energy bills.

“Germany unveiled a second support package for households and businesses, worth €65bn, bringing to some €350bn the amount earmarked so far by EU governments, the FT wrote in the same article linked to above. The UK has announced a cap on energy bills for households and businesses that is forecast to cost at least £150bn over two years.

But such is the uncertainty and fear out there that is hard to see floods of Europeans visiting car and white goods showrooms. Spending seems likely to be pared back to the essentials. And such is the extent of the buyers’ strikes being reported by the ICIS European pricing teams across many chemicals value chains that it seems as if even spending on non-durable goods may decline, if it hasn’t done already. Food shopping baskets might already be getting smaller.

Politicians will continue to do their level best to cushion the impact of the energy crisis. But how much further can they go? Europe, including the UK, had already spent €450bn with Italy and Germany spending the equivalent of 2-3% before the winter had even started, The Economist added in the same 8 September article linked to above.

It could be unfeasible to further increase government debts because of rising interest rates. New measures to cap energy prices may be ruled out, as they would counter European attempts to reduce dependence on Russian gas. Polyolefins demand destruction therefore seems almost certain to continue in Europe as the region suffers a deep recession, the worst since at least the 1970s.

Again, please don’t say I didn’t warn you

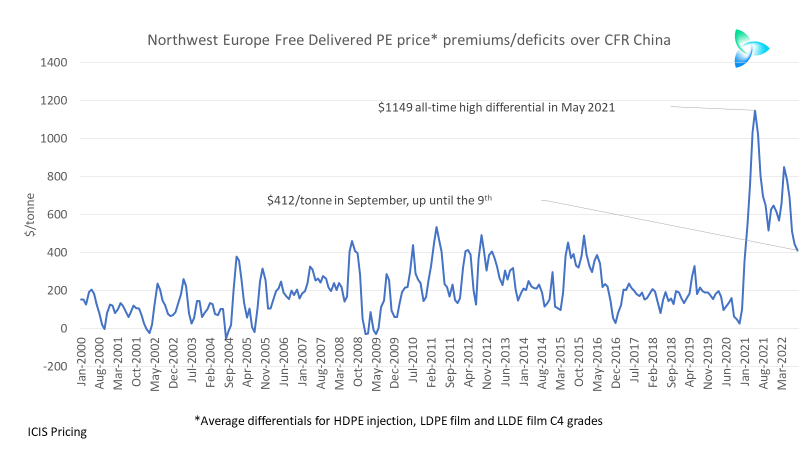

When European polyolefins prices first started to become much more expensive than some other regions in March last year, most notably compared with China, I warned that we should prepare for a return to the norm. Consider the chart below. In September 2022, up until the week ending 9 September, average European PE price premium over those in China had fallen to $412/tonne from their all-time high of $1,149/tonne in May 2021. This was 64% lower.

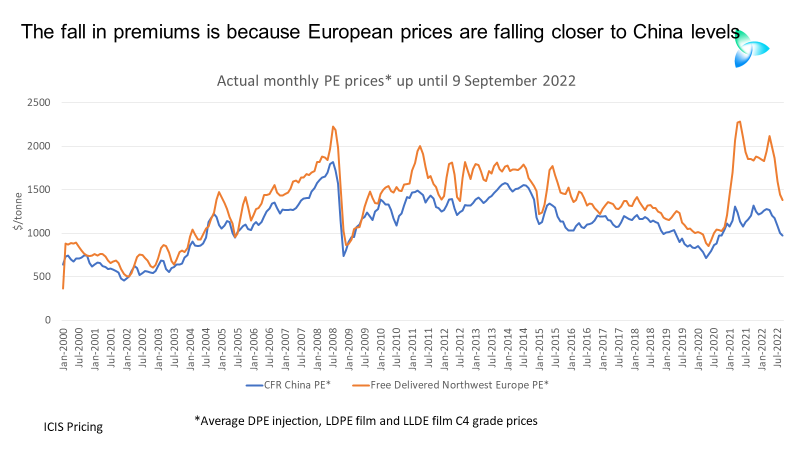

As the next chart tells us, this is not because Chinese pricing is rising to European levels; it is instead the other way round.

European PP price premiums over China were at $381/tonne in September this year, again up until 9 September, down from their historic peak of $1,28/tonne in May 2021 – a 67% decline.

This was again because European pricing was falling closer to Chinese levels, rather than the reverse, as the chart below shows.

“Bu the European markets are very different from this in China. Why the comparison?” you might say.

I disagree. This is firstly because long-term ICIS pricing historical data tell us that anomalous in pricing relationships between the regions tend to be short term. In this case, the surge in European premiums was the result of the temporary boom in demand for durable goods, the product of economic stimulus during the pandemic, that pushed Asia-Europe container freight rates much higher.

These higher container freight rates made it harder for the big exporters in the Middle East, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand etc. to relieve oversupply in China by moving surplus cargoes to Europe.

But as demand for durable goods has slowed, first on the end of pandemic stimulus and now on the great inflation shock, freight rates have come.

The ICIS pricing team heard reports of more Middle East and Asia polyolefins cargoes moving to Europe in July and August.

And DO NOT UNDERSTIMATE the impact on the European polyolefins industry and the regions’ broader economy on the major events taking place in China:

- China’s shift away from “growth for growth’s sake”. As it attempts to build a new economic growth model (we don’t know if this will work), lots of collateral damage should be expected, most notably the real-estate market, which, as the ICIS data show, has been a major driver of China’s extraordinarily strong chemicals demand growth since the property bubble began to inflate in 2009. In August this year, house prices in nearly 70 Chinese cities declined, according to Reuters.

- In the short- to medium-term, China’s zero-COVID policies will add further downward momentum to the economy. China cannot afford to scrap the policies because of the limited effectiveness of its vaccines.

- Rising chemicals and polymers self-sufficiency, the roots of which we can trace back to 2014 when the Chinese government decided to much more heavily in domestic capacity. When Beijing says it is going to do something, it usually does it.

A simple but painful truth

Despite all the complexities of this unfolding crisis, all of which we need to very closely monitor, here is a simple but painful truth: We are, in my opinion, at only the beginning of the deepest crisis the chemicals industry has faced in several decades in Europe and elsewhere.

I cannot stress enough the importance of integrated data analysis, of a razor-like focus on all the data points from all the regions in order to assess macro and micro-economic movements. There will be many micro peaks and troughs before things, in a few years, bottom out.

Every tonne you don’t produce because the demand isn’t there or the margins are too thin will be crucial in preserving revenues, as will every tonne you do produce because you’ve assessed that a viable market exists. This is where ICIS can support your business.