By John Richardson

HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL, a case in point being Chinese polypropylene (PP) imports in September this year which surged by 38% over August, the biggest percentage and volume August-September increase since our trade data records began in 1995.

The surge in imports was the result of better arbitrage and the theory that the China market would soon bottom out. Demand would have to recover because it always had done after previous brief declines, was an argument I heard.

But please be careful out there. Why should the market pick up during the remainder of this year given the clear economic direction set by the 20th Communist Party Congress?

The Congress obviously took place before the September surge in imports. But well before the important showcase event, Beijing had made crystal clear its determination to stick to the Common Prosperity economic reforms.

China has to stick to Common Prosperity because the country faces a major bad debt problem, as I discussed in my Friday 28 October post. China also confronts what is probably the world’s worst-ever demographic crisis in the context of the global importance of the Chinese economy.

I am beginning to think that we need to get past scrutiny China’s top down, very centralised, approach to dealing with its economic problems. No matter what political and economic policies China adopts, it will still struggle to overcome its bad debts and its rapidly ageing population.

The idea also took root in the PP market that zero-COVID policies would be relaxed after the Congress was over. I didn’t follow this logic because of the reported lack of effectiveness of Chinese vaccines.

Until or unless China develops its own effective versions of mRNA vaccines and administers the vaccines, the strain on the healthcare system could be too great to allow a major reboot of zero-COVID. Sure enough, the Congress re-affirmed that zero-COVID would stay in place.

Now people are suggesting that zero-COVID will be relaxed after next March’s National People’s Congress, the annual meeting of China’s parliament.

But why? It seems highly unlikely, I’d say practically impossible, that local mRNA vaccines will have been developed and adequately administered by next March.

It is certainly true that when the zero-COVID policies are relaxed, PP and other chemicals and polymers markets in China will enjoy a strong recovery.

“In the first half of 2022, households’ new savings deposits jumped more than a third year on year, to a record yuan (CNY) 10.3tr ($1.4tn) and exceeding the CNY9.9tr for all of 2021,” wrote the Financial Times in a 5 October article.

We can attribute the rise in the savings rate to the permanent implosion of the property bubble. But the end of zero-COVID will, I believe, lead to a significant pick-up in consumer spending.

But I see a recovery in “real” China PP and other chemicals demand in 2023 as unlikely. Apparent demand might rebound on higher oil prices because of inventory-building by end-users. But this is not the same as real demand, and, because of the weak economic fundamentals, an oil price-driven rise in demand would not last long.

Preliminary scenarios for China’s PP demand in 2023

Before I delve into the above chart, I must again stress that this blog represents my personal views only and is meant to encourage you to reach out to our excellent China analytics team. They can provide a much more thorough and detailed view on what is happening in the world’s most important chemicals market.

The annualised January-September China PP data (net imports and local production divided by eight and multiplied by 12) suggested a slight improvement over the January-August numbers. January-August pointed to a 1% decline in full-year 2022 demand over 2021, whereas January-September indicated flat growth over last year.

This was the result of the surge in imports described above and a further decline in Chinese PP exports. After peaking at 218,366 tonnes in April, exports had declined during each month to September. In September, China’s PP exports were just 48,037 tonnes versus 74,463 tonnes in August.

(Note that the September fall in exports was also in response to greater confidence in the Chinese economy and a shift in price differentials between China and other countries and regions. This shift in differentials and what it tells us about global PP markets is a theme I shall pick up in a later post).

The above chart, using 2022 flat demand growth over 2021 as a starting point, includes three scenarios for next year:

- Scenario 1 involves the zero-COVID policies being relaxed and a better global economy as inflationary pressures ease. Lower inflation would support China’s exports of manufactured goods which account for around 20% of the country’s GDP. Scenario 1 involves 3% demand growth in 2023 over 2022.

- Scenario 2 comprises another year of flat growth on no relaxation of zero-COVID but better global economic conditions.

- Scenario 3 sees a 3% decline in 2023 growth over this year on no relaxation of zero-COVID and a weaker global economy.

Scenario 3 is, sadly, my preferred scenario.

Early scenarios for China’s PP net exports (not net imports!) in 2023

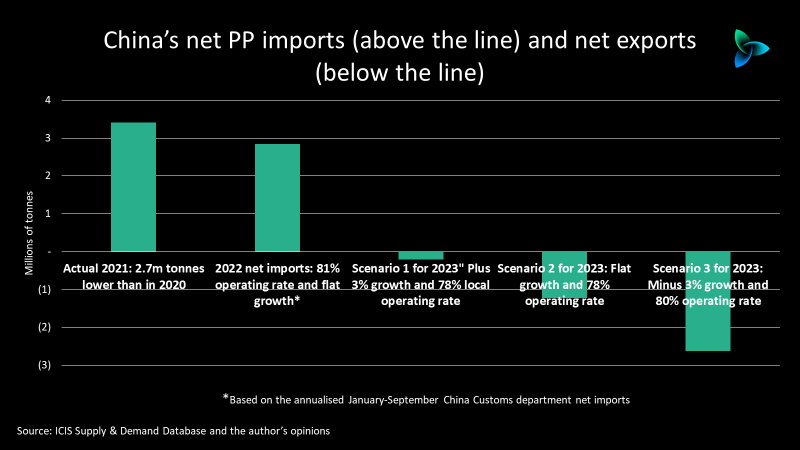

The above chart is clearly the most important chart for today. Of course, it will be wrong as it does not involve the thorough, on-the-ground analysis from our China analytics team. But it does show the increased sensitivity of China’s PP import position due to declining demand growth and rising local capacities:

- Based again on the January-September China Customs data, this year’s net imports look set to total in the region of 3m tonnes, down from 3.4m tonnes in 2021. In 2020, China’s net imports were 6.1m tonnes.

- Scenario 1 for next year is based on 3% demand growth (as in the earlier chart) and a local operating rate of 78%, the ICIS base case. With local capacity set to increase by a further 16% in 2023 over this year, this would result in China swinging into a small net export position of some 200,000 tonnes.

- Scenario 2 for 2023 involves flat demand growth and the 78% base-case operating rate. Net exports would be around 1.2m tonnes.

- Scenario 3 sees minus 3% demand growth and raises operating rates to 80% on the assumption that China will want to become a bigger export player. Net exports would be in the region of 2.6m tonnes.

Conclusion: It is what it is, so adapt your strategies

To repeat, there is no going back. The Financial Times headline for a 27 October article illustrates how the new China represents a broader economic challenge: ‘German exporters rethink €100bn love affair with China”.

The newspaper added: “Zero-COVID and domestic competition endanger trading relationship” as it discussed the difficulties facing the country’s Mittelstand machinery exporters to China.

The only way up and out of this crisis is for chemicals companies to accept that China will never be the same again. They then need to focus on more sustainable service-based and localised business models. What applies to chemicals applies to every other industrial sector.