By John Richardson

F0LLOWING last week’s 20th Communist Party Congress, overseas commentary has been focused on how China’s top-down approach to economic policy is not what the country needs as China attempts to escape its middle-income trap.

Concerns have also been expressed that because China and the US are drifting further apart, China will struggle to access the higher-value technologies it needs, especially access to critical semiconductor technologies. No modern economy can operate without access to high-value semiconductor knowhow.

The tone of the speeches during the Congress gave no indication of a China-US rapprochement.

On the other side of the new great divide, there is firm US bipartisan support for treating China as an opponent. Before 2018, China was seen as a partner. The new approach to China is one of the few areas of agreement between Democrats and Republicans.

An excellent webinar by the Financial Times, the recording of which, if you are a subscriber you can listen to here, is the best summary I have found of all the policy concerns relating to the 20th Congress.

But I said in my 26 October post, nobody really knows whether China’s policy direction will deliver what’s needed. Perhaps, though, no set of policies can work given the deck of economic cards China has been dealt.

This was an argument I first started to make in 2014. Even way back then, it seemed clear that China’s rapidly ageing population represented a huge, huge challenge. China has long been in danger of becoming old before its rich, to use the old cliché.

Ruchir Sharma, chairman of Rockefeller International, formerly emerging markets investor at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, highlighted the demographic mountain China needs to climb in this 24 October Financial Times article.

“China is now a middle-income country, a stage when many economies naturally start to slow given the higher base. Its per capita income is currently $12,500, one-fifth that of the US,” he wrote.

The world had 38 advanced economies, all of which grew past the $12,500 mark in the decade following the Second World War, he added.

Only 19 of these countries enjoyed GDP growth at 2.5% per year or more in the ten years after World War II. They did so with a boost from more workers as the average working age population of these countries grew at 1.2% a year. China’s working-age population began to shrink in 2015.

Here is a reminder of a 2019 American Enterprise Institute study:

- Between 2015 and 2040, China’s population aged 50 and over will increase by roughly 250m as the population under 50 falls by the same amount. During the same years the 15-29 age group – which across all modern societies has the highest education and is the most IT and tech savvy – will shrink by 75m.

- Equally as bad will be the fall in the 30-49 age group during this same time frame. It is forecast to fall by a quarter or by more than 100m. This is the generation that tends to be the most innovative and entrepreneurial.

- The only cohort expected to grow is the 50-64 age group and those over 64. In 2015-2020, the 65+ population will jump by almost 150% – from 135m to close to 340m.

“Growth in the long term depends on more workers using more capital and using it more efficiently (productivity). China, with a shrinking population and declining productivity growth, has been growing by injecting more capital into the economy at an unsustainable rate,” added Ruchir in the same article.

The risks of declining returns on capital were evident from 2009 onwards following the launch of China’s huge economic stimulus package.

But what choice did China really have at the time given the potential loss of tens of millions of jobs because of the Global Financial Crisis? I’d suggest no choice at all.

And let’s remember that the global chemicals industry benefited enormously from China’s giant economic stimulus programme. Global consumption roared back after a brief dip in late 2008, thanks almost entirely to China.

But still, it has been evident for a long time that the road for debt-fuelled growth was always going to run out because of very bad demographics and falling productivity.

Here are some more worrying statistics from Ruchir’s article: of the 19 countries that achieved 2.5% per year GDP growth in the ten years after World War II, total debts averaged 170% of GDP. China’s debts are estimated at 275% of GDP.

In other words, China may not achieve average GDP growth of 2.5% over the next decade and more. If it is going to escape its middle-income trap, China must grow at around double this – an average of 5% per annum – over the next ten years.

Implications for China’s polymers demand

Before I provide you with scenarios for what this could mean for China’s polymers demand, remember to never underestimate China. Time and again, policymakers have proved the sceptics wrong.

But even policy success doesn’t necessarily mean Chinese GDP growth of at least 2.5% per year over the next few decades. Perhaps China will lead the world in “less is more” and “build to last”. China may set the template for breaking the conventional link between prosperity, however one defines prosperity, and strong GDP growth.

In the end, therefore, the outcome of policy success or failure could be the same for polymers demand: lower-than-expected consumption growth in the world’s most important market.

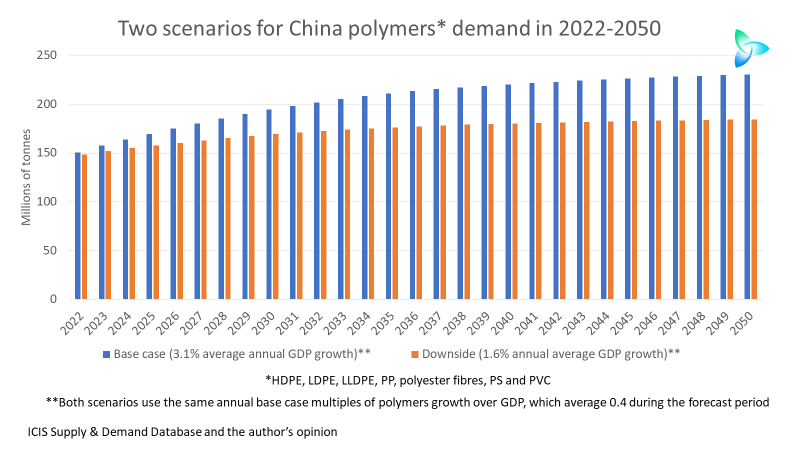

Our excellent ICIS Supply & Demand Database provides a sound base case for Chinese 2022-2050 demand growth in the seven major synthetic resins – high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density PE (LDPE), linear-low density PE (LLDPE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyester fibres.

Our base case assumes that 2022-2050 Chinese GDP growth will average 3.1% in 2022-2050. This would be a sharp decline from actual average 1978-2021 GDP growth of 9.2%. 1978 is when our database begins.

The multiple of demand growth for seven big synthetic resins over GDP in 1978-2021 averaged 1.6. As China’s economy and its polymers market matures, we forecast that this multiple will fall to 0.4 in 2022-2050. A decline to below zero towards the end of the forecast period brings the average down.

You can see the impact of this base case for 2022-2050 China polymers demand in the above chart. In the same chart, my highly unscientific downside involves reducing annual GDP growth to half of our 2022-2050 base case assumptions. This leaves average GDP growth during the period at around 1.6%. I kept the same annual multiples of polymers consumption growth over GDP used for our base case.

The differences are, of course, breathtakingly big:

- Cumulative downside demand would total 5bn – 910m tonnes lower than our base case.

- Assuming the unlikely event of the rest of the world being unaffected by China growing much slower than expected, global growth in polymers demand between 2022 and 2050 would be 197m tonnes under the downside. This would compare with 230m tonnes under the base case.

- Under the downside, cumulative global demand for polymers in 2022-2050 would be around 12.8bn tonnes versus 13.9bn tonnes under the base case.

Conclusion: Now the real scenario work must begin

As always, the data and thinking presented in this blog post are nowhere close to thorough scenario work. For proper scenario work, you need to contact our consulting team.

As the chemicals industry crisis gathers pace, much more detailed and wide-ranging scenario work is essential to “future proof” businesses. A key element of the crisis is the emergence of a very different China.

And central to the success of chemicals companies will be more environmentally focused, service-based growth models. This would make lower-than-expected growth in China polymers demand of little consequence.