By John Richardson

IN SOME RESPECTS, the above is an example of the “more that things change, the more they stay the same” (take it away one more time, Professor, and the rest of the greatest rock band of all time).

The zig-zag lines on the left-hand side of the chart, as we head towards the bottom of this downcycle, require chemical and polymer producers to make many more correct decisions on “what, when and where to sell” than during upcycles. It has always been thus.

In upcycles, there ae so many profits sloshing around that even if companies often get the “what, when and where to sell” wrong most of the time, they still make good money. But as we head towards the bottom of this downcycle, as I keep reminding everyone:

- Every tonne of polymer you decide not to produce because there isn’t a viable market will save vital revenues – especially as feedstock costs will remain very volatile.

- Every tonne of polymer you do produce because the market works will earn you crucial money at a time of declining overall sales.

As I said, in some respects, the more that things change, the more they stay the same. I first saw the above chart when it was drawn on the back of a beermat by a consultant (I was a journalist then) in a bar in Singapore during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. I still have the beermat.

But this downcycle is so, so different from anything I have seen in the 25 years I have reported on and analysed the chemicals industry.

The Asian Financial Crisis was essentially over by 1999, and, as its title suggests, it mainly affected Asia – along with a few other emerging markets.

When the Dotcom Bubble burst in 2000-2001, there was only a marginal impact on the chemicals industry because China had already started to power global demand. This was especially so from late 2001 onwards, after China was given admission to the World Trade Organization, leading to the removal of the tariffs and quotas that had restricted China’s exports to the West.

Global Financial Crisis? What crisis?

Some chemicals companies were close to bankruptcy in late 2008 because the collapse in oil prices left them sitting on high-priced inventories.

But then, Whoosh! In January of the following year, China launched the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus package and global demand went through the roof. China’s polypropylene (PP) demand increased by 35% in 2009 over the previous year.

Ever since that year, up until very recently, China bankrolled the global chemicals industry. The country’s demand growth beat expectations as China’s share of global consumption significantly outperformed its share of the global population.

There was a brief flutter of alarm in late 2014 when the commodity price bubble popped. But this was beneficial to chemicals as it made feedstocks cheaper.

In late 2019, as Asian olefins and polyolefins margins turned negative, it seemed as if years of strong profits were finally over as we entered a classic overcapacity-driven downcycle.

But then the pandemic arrived. Chemicals supply was reduced as refineries cut operating rates due to the fall in demand for transportation fuels. Demand for chemicals increased because of government stimulus as bored, rich Westerners in lockdowns bought lots of durable goods.

Meanwhile, the China demand engine kept purring away after a very brief scare in early 2020.

As China became the first country in the world to emerge from lockdowns, it was able to add to its already dominant share of global manufacturing-goods exports. China enjoyed an export-powered recovery as it met most of the demand for durable goods among the rich Westerners in lockdown.

Even the weather helped the chemicals industry (at least those who were still producing), when the Texas Winter Storm in February 2021 sharply curtailed global supply just as pandemic economic stimulus was beginning to tail-off. Hurricanes in the US later in the same year further limited supply.

But for those who were taking notice, including this blog, signs of stress emerged in early 2021. China was slowing down, exacerbating the impact of large local capacity additions.

The slowdown was firstly the result of an inevitable cooling off from the export-drive bubble year of 2020. Then from August 2021, we saw the biggest shift in economic policy since Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992.

There were Deniers, of course, who said that the Early Adopters (the blog was an Early Adopter) didn’t know what they were talking about.

But it was clear to me that the launch of Common Prosperity meant, and still means, no more growth for growth’s sake. Debt control, greater income equality and improved environmental protection are long-term cornerstones of the new policy direction.

The standout symptom of this new direction is the permanent deflation of China’s real-estate bubble. The post-2009 stimulus-fuelled housing bubble is why China’s chemicals demand has taken off since that year, making China by far the biggest demand region.

Then we saw the Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s zero-COVID policies. The invasion has led to inflation levels we haven’t seen since the 1970s and an energy crisis in Europe; zero-COVID means that, even if Beijing went back to old-style massive stimulus, consumer sentiment will likely remain so weak that the extra available money would likely not be spent.

Meanwhile, China’s chemicals self-sufficiency will continue to increase as more local capacity is added. Local demand growth is likely to be negative in 2022 – and quite possibly in 2023 as well.

This is not a typical downcycle. It is instead one that will drag on and on, well beyond 2023, in my opinion.

How do you make the right decisions on “what, when and where to sell”? Getting the decisions right is going to be more important than in previous downturns for the reasons detailed above.

You need to focus on comparative netbacks between all the different markets, using ICIS pricing data. Equally important is tapping into our expertise on supply and demand in every country and region – and on the “mood music”, the sentiment, in each market.

Let me provide some sample slides to point you in the right direction.

Overseas HDPE film premiums over China remain at historic highs

The chart below is a monthly version of the weekly charts I have been providing from mid-September. The chart shows high-density PE (HDPE) film grade price premiums and discounts for a selected group of countries and regions over China since January 2020.

Premiums have risen to historic highs since March 2021, when polyolefin markets de-globalised as the slowdown in China combined with high container freight rates, limiting the ability to move oversupply out of northeast and southeast Asia.

As you can see, premiums have fallen since April 2022, but remain historically very strong.

One of the extra layers of market knowledge missing is the extent to which we are seeing demand destruction in Europe because of its energy crisis. The $187/tonne month-on-month fall in northwest Europe (NWE) indicates demand destruction.

The next chart shows how actual average HDPE film grade prices in the selected group of countries and regions have fallen closer to Chinese levels since April this year.

The chart below tells us that as China’s import falls, more accurately assessing the strength of imports in markets outside has become a critical success factor.

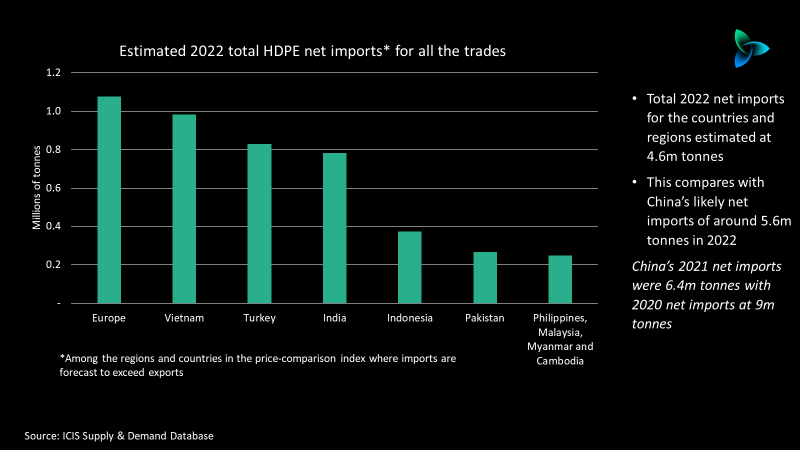

The regions and countries listed above help make up my HDPE film grade price-comparison index. The above locations are also expected to be net importers of all grades of HDPE in 2022 to a total of 4.6m tonnes.

Overseas PP injection premiums over China also remain strong

As with HDPE film grade, the monthly polypropylene (PP) injection-grade chart for September this year shows that overseas premiums over China fell compared with August but remained historically very strong. Again, note the steep fall in NWE prices as a cause for concern.

As with HDPE film grade, overseas PP injection grade actual prices have fallen towards Chinese levels since April this year.

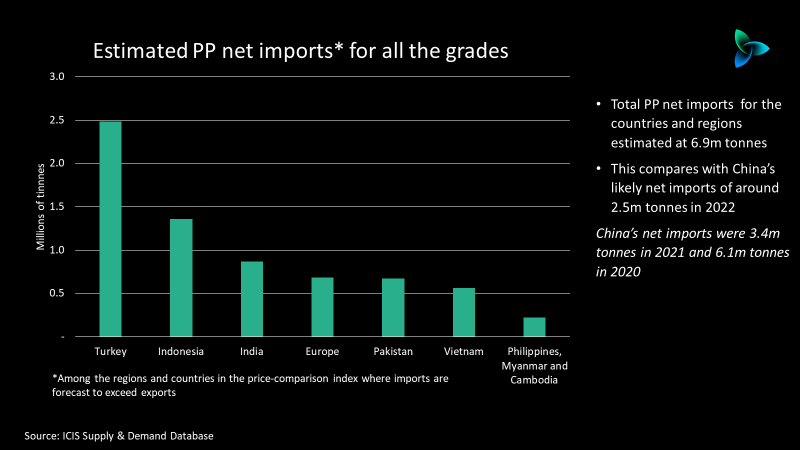

The next slide shows the importance of focusing on all import opportunities. These are again estimates for net imports all grades of PP.

Total PP net imports in the countries and regions listed above is estimated at 6.9m tonnes in 2022. China’s net imports in 2022 look set to be in the region of 2.5m tonnes.

These slides just scratch the surface of what’s required

Missing is comparative netback analysis for each of the countries and regions detailed above. The above chart only provides averages for all the countries and regions together.

The net import slides are just a snapshot in time. They need constantly updating as does the demand and supply context behind every data point. Equally important is the “mood music”, the sentiment, in each market as sentiment makes prices.

For more help, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.