By John Richardson

A SELECTIVE READING of the news is giving polyolefins market participants confidence. They see the relaxation of zero-COVID restrictions in some Chinese cities as a sign that the worst is over and that China’s consumer spending will soon come roaring back.

When China eventually gets past zero-COVID there will be lots of “revenge spending” as China’s shoppers catch up on lost time.

“Thanks to lockdowns and financial volatility, citizens added over 13tr yuan to their savings in 2022 in an economy with one of the world’s highest savings rates. Household deposits totalled nearly $17tr by October,” wrote Reuters in this 5 December article.

Reuters quoted Standard Chartered research which estimated that if urban households drew down half of their excess savings accumulated since 2020, this would add one percentage point to GDP growth in 2023.

But as I have been arguing since August 2021 following the Common Prosperity policy pivot and as Reuters also points out, the deflation of the property bubble will continue after zero-COVID comes to an end as this is a long-term government objective.

One of the reasons why savings rates have gone up is, of course, China’s coronavirus restrictions. Another reason is the end of confidence in the government “put option”- that Beijing would always intervene to ensure land and property prices would not fall.

So, yes, expect a bounce in consumer spending post zero-COVID and increases in polyolefins demand and pricing. But the end of the property bubble, which is worth no less than 29% of China’s GDP, will limit the extent of the recovery.

And as I’ve been warning since May this year, when I quoted a Nature magazine article on the China healthcare system, be careful what you wish for. A sudden relaxation of the zero-COVID rules could, lead to the number of coronavirus cases requiring hospital treatment at 15.6 times the capacity of hospital beds in China, according to Nature.

Although China managed to build a 1,000-bed hospital in Wuhan in just six days at the height of the pandemic in 2020, this important Economist briefing warned that providing healthcare coverage to deal with the wave of cases as China exited zero-COVID would take considerable time.

Positive effects of end to zero-COVID may not be felt until 2024

“Training new ICU [intensive care unit] medics takes years. Only a small minority of Chinese doctors have seven-year medical degrees. Indeed, 42% of doctors do not have a university degree of any sort,” wrote the Economist in its 1 December briefing.

The magazine said that China had 4.3 ICU beds per 100,000 people.In comparison, this 1 September 2022 World Population Review study found that the US had 34.7 ICU beds per 100,000 people.

China was not ready for an orderly exit from lockdowns, Yanzhong Huang of Seton Hall University in America told the Economist.

Only 40% of those over 80 had received three doses of local vaccines that provided good protection against severe symptoms, said the magazine.

“A campaign to encourage the old to get jabbed, announced on November 29th, will take time. Giving everyone a fourth booster would allow for a much safer exit but work on that has barely begun,” wrote the Economist.

The effectiveness of local vaccines is reported to wane after six months. Politics appear to be getting in the way of making extensive use of longer-lasting foreign vaccines.

A sudden end to zero-COVID would likely lead to an unsustainable spike in deaths and hospital cases, forcing restrictions to be re-imposed.

Even a gradual winding back of zero-COVID might not be easy. The Economist warned that during the exit phase, “chaotic conditions, if the transmission of the virus is allowed to proceed fairly rapidly, could last for three months at a minimum.”

Ting Lu of Nomura, a Japanese bank, was quoted by the magazine as saying that regions covered by lockdowns during the exit phase could account for as much as 40% of GDP, with output falling over one or two quarters.

“Even if China were to end zero-COVID immediately, the positive economic effects would probably not be felt until 2024, say analysts at Capital Economics,” the Economist added.

A slightly revised outlook for PP demand in 2022

Never say never, though, no matter how unlikely an event might be. This has led me to revise my 2023 outlook for China’s polypropylene (PP).

In a 23 November blog post, I projected that under the best-case outcome, China’s PP demand would grow by 3% in 2023. In retrospect, this would be a too-modest recovery in demand if zero-COVID were to end next year with no serious consequences.

The chart below involves a 6% increase in China’s PP demand in 2023. This would be five percentage points higher than the 1% growth in 2022 demand suggested by the January-October data. But as you can probably tell, I rate as low the chances of Scenario 1 happening.

Scenario 1 would see China’s PP demand reaching 36.4m tonnes in 2023, up from this year’s 34.3m tonnes. The 6% increase would involve both the end of zero-COVID and an improvement in the global economy. Stronger global conditions would support China’s exports that are worth around 20% of GDP.

There are signs that global inflation may have peaked as supply-chain shortages resulting from the pandemic begin to ease. Falling energy prices have reduced fuel and food costs.

Under Scenario 2, zero-COVID restrictions would stay in place, but global economic conditions would improve. This scenario involves PP demand contracting by 1% over 2023, leaving the market at around 34.6m tonnes.

The worst-case outcome, Scenario 3, would see next year’s demand fall by 3% to 33.3m tonnes. Zero-COVID restrictions would remain as the global economy worsened.

Energy has often been used a geopolitical weapon. But in recent months, the use of the weapon has increased. Some 16% of European liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports come from Russia. What would happen if these supplies were diverted elsewhere, for instance?

In other words, the global economy could deteriorate next year.

Even if demand growth is 6% in 2023, just look at the effect on net imports

Now let’s look at what could happen to China’s PP net imports or net exports in 2023.

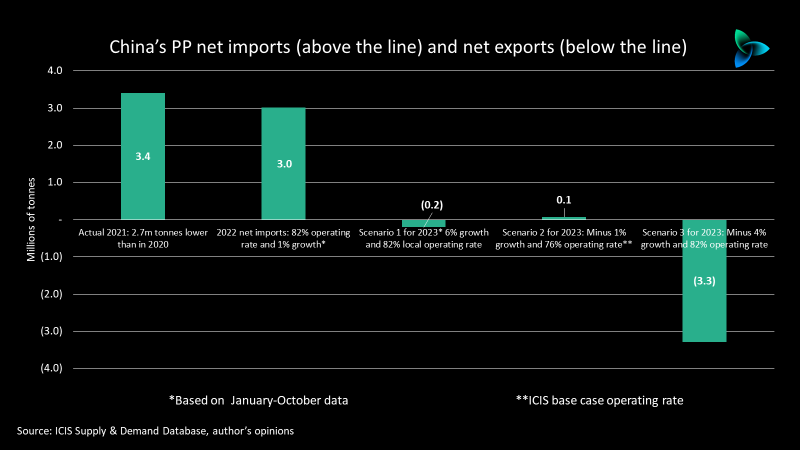

This year’s net imports look set to be around 3m tonnes based on the January-October China Customs department data. Actual 2021 net imports were 3.4m tonnes – 2.7m tonnes lower than in 2020.

Even factoring in 2023 demand growth of 6%, the prospects for next year’s export trade to China do not look good.

The reason is the 17% increase in China’s capacity that we forecast for 2023 over this year to 44.6m tonnes/year. This would follow previous years of big capacity increases, which are part of the government’s push to achieve much greater self-sufficiency in chemicals and polymers.

If demand growth were to reach 6%, it seems reasonable to assume that 2023 operating rates would be around their level so far this year – 82%. Higher demand growth would improve PP profitability as it would be accompanied by stronger pricing.

Scenario 1 therefore involves 6% growth, an 82% operating rate and all the new capacity we forecast coming online. China would swing into a net export position of around 200,000 tonnes.

Under Scenario 2, I assume that the base case operating rate for 2023 in the ICIS Supply & Demand Database – just 76% – happens.

Combine this with demand growth at minus 1% and China would end up with net exports of some 100,000 tonnes, again assuming all the new capacity comes on-stream on schedule.

The worst-case outcome, Scenario 3, assumes that even in the weakest demand growth outcome of minus 3%, China still runs its plants at this year’s operating rate of 82%.

This would be in order to maximise export earnings, perhaps supported by continued yuan weakness against the US dollar. This outcome would see China swing into a net export position of 3.3m tonnes, once again assuming no delays in start-ups of new plants.

As recently as 2021, China accounted for no less than 42% of total global PP net imports among the countries and regions that imported more than they exported.

The chart below shows our estimates of the remaining big global net import markets in 2023.

Conclusion: Key takeaways for 2023

Don’t get sucked under the tide of optimism washing through polyolefins markets resulting from the relaxation of zero-COVID restrictions in some Chinese cities. This does not mean that China is anywhere close to moving beyond its challenges.

Your base case for PP production and sales targets for 2023 must involve a prolonged exit from zero-COVID. No economic benefits from the gradual unwinding of restrictions should be expected until 2024.

And even in 2024, the recovery will be limited by the Common Prosperity economic reforms. The deflation of the property bubble will restrict PP demand growth.

China’s demand for PP imports will decline further next year. If you are one of the major PP exporters in the Middle East, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand, you must focus more on the remaining big import markets listed in the slide immediately above.