By John Richardson

AGAIN, PLEASE DON’T SAY I didn’t warn you. The chart below is an example of how PE prices have started to re-globalise, as I said they would when they began to de-globalise from March 2021 onwards.

What applies to the declining polyethylene (PE) price differentials between Europe and China applies to all the other countries and regions versus China. The pattern has been the same in polypropylene (PP) over recent months.

A reason why average PE price premiums in northwest Europe (NWE) over China reached a record high in May 2021, following a steep run-up from the start of the year, was pandemic-related government economic stimulus.

Meanwhile, China’s demand growth was declining after a bumper year in 2020. The bumper year was the result of a surge in China’s exports of durable goods in the West as bored lockdowners bought game consoles, computers and garden furniture etc. The products came wrapped in PE and were in some cases also made from PE.

As China’s demand moderated, its local supply increased as more capacity came onstream. Oversupply was trapped in NEA because expensive container freight rates and lack of container space made it difficult for PE exporters to divert unwanted supply elsewhere. The tight container market was the result of the pandemic.

Then we had the Texas Winter Storm in February 2021 followed by US hurricanes later in the same year which sharply curtailed US PE export availability. Europe, which is a big net importer of high-density PE (HDPE) and linear-low density (LLDPE), receives a lot of its imports from the US. In low-density PE (LDPE), however, Europe is a net exporter.

As you can see from the chart, the average NWE PE monthly price premium over China reached $1,149/tonne/tonne in May 2021 – the highest since our price assessments began in January 2000.

Since then, price premiums have seesawed. But they remain far lower than their peak. In 1-9 December 2022 for example, the premium was $452/tonne.

The next chart helps explain why re-globalisation is underway. Falling container freight rates are making it easier for the big exporters in the US, the Middle East, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand to divert cargoes away from China, where 2022 demand growth looks likely to be negative.

The chart shows composite container-freight indices, compiled by the maritime and shipping consultancy and research company, Drewry. The indices are close to or below their pre-pandemic levels.

The collapse in container rates is the result of the demand destruction caused by the surge in global inflation. There has also been a cycle of demand for durable goods and into services as economies have re-opened now that the pandemic has past its peak in most countries.

The surge in inflation is affecting European demand for PE as my ICIS Pricing colleagues, Vicky Ellis, Ben Monroe-Lake, Samantha Wright and Linda Naylor highlight in their latest European PE price assessment report.

“Demand remains dampened by inflationary pressures. Packaging for food has been fairly protected, though takeaway containers are seeing weaker demand. Industrial packaging has been weak for months,” they wrote in their 9 December report.

Europe’s PE market in 2023

The ICIS team, in the same report, refer to one of the many complications clouding the outlook for the European PE market in 2023.

“Optimism for the start of 2023 is thin, with concern that energy may return as a major pressure if temperatures plunge,” they said.

Temperatures in Northern Europe are expected to plunge next week with snow and ice predicted.

Because of increased interest rates and higher energy costs, more homeowners will be faced with the choice of paying the mortgage or turning the heating on. An extended cold snap would also further damage consumer spending and therefore PE demand.

At least, though, it appears as if European gas shortages won’t happen this winter. “European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said the EU’s gas supply is ‘safe this winter,’” wrote Politico in a 12 December article.

This should mean no European PE production costs resulting from lack of gas supplies. But the chart below illustrates the impact of high energy costs and weak demand across all European chemicals production.

European chemicals capacity utilisation was just 55.2% in October, close to its all-time low in late 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis As you can see, operating rates in the regions were very low.

But if inflation has peaked in Europe (there are some encouraging signs to this effect), perhaps the downward pressure on PE demand will ease a little in 2023.

Beware, though, of the risk that Russia could further weaponize energy to achieve its geopolitical objectives. Some 16% of European LNG supply comes from Russia. Pipeline gas supplies from Russia to Europe may be further reduced.

And Ursula von Leyden, in a joint statement with Fatih Birol from the International Energy Agency, warned the EU might face a shortfall of up to 30bn cubic meters of gas during the 2023/2024 winter.

“We are now turning our focus to preparing [for] 2023, and the next winter,” von der Leyen said.

“For this, Europe needs to step up its efforts in several fields, from international outreach to joint purchasing of gas and scaling up and speeding up renewables and reducing demand,” she added in the joint statement.

Gas shortages would quite obviously further damage the European economy through manufacturing shutdowns, as the priority would be maintaining gas supply to households.

But from the rather insensitive perspective of the global PE demand balance, reduced European production would tighten supply. European PE prices might increase as imports rise.

Absent gas-induced production cuts, however, the decline in European PE price premiums over China may continue.

Consider the chart below which shows actual monthly NWE prices versus those in China since our price assessments began in January 2000 until 1-9 December 2022.

The question posed on the chart is one that I’ve been highlighting since container freight rates started declining: Will Chinese prices recover to overseas levels, or will overseas prices be pulled closer to Chinese levels?

The vaccination and healthcare complications of China’s exit from the zero-COVID policies, combined with yet more domestic PE capacity, has created a scenario where the Chinese polyolefins market remains as depressed in 2023 as it has been in 2022.

And here’s the thing: The average NWE January 2000-December 2020 monthly price premium over China was $193/tonne. But from 1 January 2021 until 9 December 2022, the premium reached $649/tonne.

What would European PE profitability look like if the region’s premiums returned much closer to their long-term average? If this were to happen, the response could be closure of less efficient European plants in order to bring the market back into better balance.

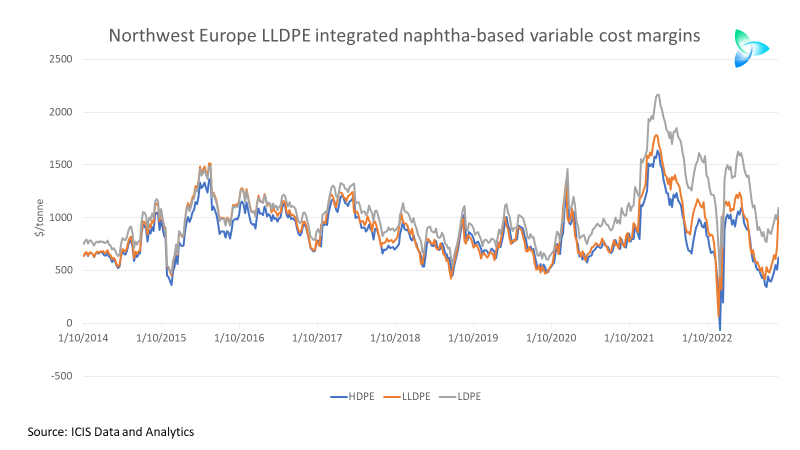

The chart below shows our assessments of European HDPE, LDPE and LLDPE margins at typical or average European plants. While volumes are a problem, profitability is holding up well.

And we must not overlook increasing global PE supply, especially supply from the US. The chart below shows actual 2020-2021 US PE exports, a full-year 2022 estimate of exports based in the January-October trade data and forecasts for 2023.

Conclusion: Stay close to ICIS

Confused? You may well be as the outlook has never been as muddled as this.

What if China doesn’t recover from zero-COVID in 2023? What if it does? What if inflation has peaked? Or it could inflation increase on new disruptions to energy supply?

What would the effect be on European PE production if there are gas shortages during the 2023/2024 winter? How would the cutbacks impact pricing and imports.

These are just some of the challenges we face in working out what’s going to happen next year. Stay close to ICIS and together we’ll get through this crisis.