IN THE WEST, confidence in the effectiveness of government policy seems to be low and so probably doesn’t have much of an impact on how people spend their money.

Take Perth in Australia, where I live, as an example. When the Federal Government’s JobKeeper payments were available at the height of the pandemic, lots of young tradies were better off than when they were working.

The extra money was largely spent not because of faith that politicians were getting it right, but because the cash was burning holes in numerous pockets. The Perth economy, as a result, did very well in 2020-2021.

China is, however, a managed economy which means that there must be a high level of confidence in many aspects of how the economy is being managed.

A large portion of 2009-2021 Chinese economic growth was built a house of cards – the real estate sector, which is worth some 29% of GDP.

What underpinned confidence in the property market was the government “put option”, the belief that Beijing would never let land and real-estate prices fall because the politicians had market events entirely under their control.

Even if people worried about the fundamentals of all the empty apartments as the population aged and as prices rose beyond the reach of the vast majority, they believed in the put option.

“China’s housing market flipped from being a growth driver to an economic drag in 2022, with sales slumping, prices falling and widespread job losses,” the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) wrote in this 19 January article.

Sales of new residential properties fell 28% last year to $1.7tr in value, a five-year low. By floor area, they dropped to their lowest level in nearly a decade after debt defaults by developers, the WSJ added.

“Land sales by area declined by 53% in 2022 to a level below that of 1999, the year China’s National Bureau of Statistics began releasing the data,” the WSJ added.

Citigroup analysts quoted by Bloomberg in this 6 January article forecast that new home sales would fall by a further 25% in 2023. The property recovery would be constrained by reduced supply and buyers’ expectations, the wire service added.

The sudden reversal of the zero-COVID policies at the end of last November and the subsequent rapid rise in infections appear to be other areas of concern for consumers and investors.

There is also the uncertainty of not knowing when the exit wave will peak. Have we already reached the peak? Even if this is the case, might there be a second or even third wave of infections as we’ve seen in other countries?

Nobody has a clue over the extent to which all the above will hold back a recovery in 2023, as this set of circumstances is entirely unprecedented. We are also dealing with an intangible rather than hard numbers: the confidence to spend and invest money.

But there are some hard numbers that point towards the strength of the recovery that will inevitably occur when China gets on top of its exit wave. I say inevitably because large portions of the economy were shut down during zero-COVID.

Chinese households had accumulated $2.6tr of bank deposits last year alone because the strict anti-coronavirus policies had crushed consumer spending, said the Financial Times (FT) in this 24 January article.

“Yet the world may be misjudging China’s willingness to spend, according to some analysts, who said only about $200bn of the pool of savings might actually be unleashed this year despite Beijing’s best efforts to stoke a rapid rebound,” wrote the FT.

Half of last year’s excess savings were reported by the FT to be the result of investors shifting money from high-risk investment products, largely in real estate, to bank deposits. This is one of the results of the end of the property bubble.

Experts quoted by FT said that a further portion of the rise in savings was because of a “natural” rise in incomes that was posited in the banks.

Four scenarios for China’s petrochemicals demand in 2023

I was taught a long time ago by petrochemical producers that the only sensible approach to estimating demand was scenarios and that three scenarios made the most sense: best, medium and worst case.

Producers could then set sales and production targets under the three different outcomes while ensuring that they would still make money even under the worst-case outcome.

This year, though, we need four scenarios for China based on the following:

- Scenario 1: The economy comes roaring back with consumer and investor confidence high. “Revenge spending” leads to restaurants and shops, airplanes, buses and metro cars back at full capacity. Investors, including overseas investors, resume big new investments on catering to the “rising number” of middle-class Chinese.

- Scenario 2: Shops and restaurants reopen as China quickly gets on top of its exit wave. But weak exports (exports are worth some 20% of GDP) hinder the recovery. So do cautious consumers and investors because of worries about what lies around the economic corner.

- Scenario 3: Unlike in Scenarios 1 and 2, growth is still negative for some petrochemicals and polymers following negative growth in 2022. This is the result of a very tepid recovery in consumer and investor confidence, as exports exert a major drag on growth due to persistently high overseas inflation.

- Scenario 4: Petrochemicals demand growth is deeply negative on either or both a lack of confidence and the exit wave lasting most of the year. Exports just about collapse because of overseas economic problems.

New scenarios for China’s PE demand in 2023

Hence, the slide below where I have extended my earlier three scenarios for China’s polyethylene (PE) demand in 2023 to four.

Scenario 1, the ICIS base case, sees 4% average growth across the three grades of PE.

This would leave this year’s total demand at around 39m tonnes, up from 2022’s 38m tonnes (note that what should be close to the final demand numbers for last year are now available. This follows the publication of the full trade data for 2022 and ICIS estimates of January-December local production).

Scenario 2, my preferred scenario, would see 2023 demand at approximately 38.5m tonnes (2% higher) with Scenario 3 (2% lower) at 37m tonnes and Scenario 4 (5% lower) at 36m tonnes.

The implications for net PE imports in 2023

Here are my four new scenarios for China’s net PE imports in 2023.

Scenario 1 would see total 2023 net imports at 13m tonnes, down from last year’s 13.5m tonnes. Under Scenario 2, net imports would drop to some 12.5m tonnes; Scenario 3 to 11m tonnes and Scenario 4 to 10m tonnes.

Note the big range of outcomes for this year’s high-density PE (HDPE) net imports from 5.1m tonnes under Scenario 1 to just 3.4m tonnes under Scenario 4. This would compare with last year’s net imports of 5.6m tonnes.

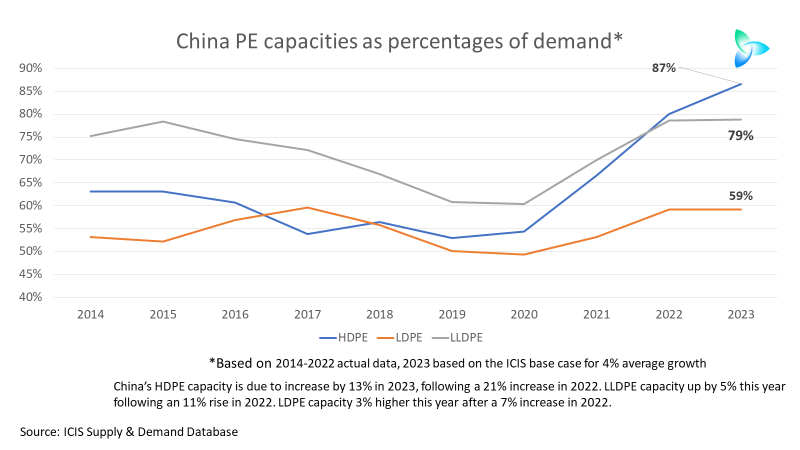

HDPE is the most exposed of the three grades to sharp downsides because of the extent of its capacity build-up relative to demand, as the next chart illustrates. The year 2014 was pivotal as this was when government policy changed towards an aggressive push for greater petrochemicals self-sufficiency.

The potential for as little as 3.4m tonnes of Chinese net HDPE imports in 2023 would throw greater pressure on the other big net import markets during a period of record-high oversupply:

- Annual global capacity in excess of demand averaged 4m tonnes/year in 2000-2021, according to ICIS. We forecast that this will rise to to 12.2m tonnes in 2023.

- This is reflected in global operating rates. Operating rates in 2000-2021 averaged 88%. Capacity utilisation is forecast to fall to just 78% this yea,r

China’s HDPE capacity is due to increase by 13% in 2023 following a 21% increase in 2022. Linear low- density (LLDPE) capacity is forecast to be 5% higher this year following an 11% rise in 2022. Low-density PE (LDPE) capacity is expected to be 3% higher in 2023 after a 7% rise last year.

The chart below details the ICIS forecasts for the size of the HDPE net import markets aside from China in 2023.

Conclusion: It has never been as complicated as this

We cannot even take for granted a strong Chinese economic recovery in 2023, something we’ve always been able to rely on over the past 30 years every time there has been a brief and mild downturn.

Neither can we be sure what the effects will be on energy costs if China does see a big economic recovery. In such an event, oil prices could go up to well over $100/bbl.

Has inflation in the west peaked? The signs are hopeful so far this year. But how would a strong China recovery affect inflation in the West, along with any further geopolitically driven interruptions in oil and gas supply?

This muddled macroeconomic environment exists during a period of all-time oversupply in PE and polypropylene (PP). Never before has ICIS forecast capacity so much in excess of demand in 2023 and beyond across all grades of PE and in PP.

But, we don’t know how many new start-ups will delayed or how many plants will shut down temporarily or even permanently.

And while petrochemicals markets everywhere will be affected by the global macroeconomic outcomes, each market will have its regional characteristics.

This is why a deep dive into the demand, supply and pricing behaviours of all the regions will be essential. This very much applies to the above chart on HDPE in the context of what could be much weaker Chinese net imports.

This is where ICIS can help you through constantly updated data sets such as the ones illustrated above, along with our market intelligence. For more information about how we can support your business, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com