By John Richardson

PRIDE COMES BEFORE a fall, of course. Nevertheless, last year I was pretty much on the money. From March onwards, I forecast low or negative China demand growth for the three grades of polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), as China’s zero-COVID lockdowns took place along with the real-estate slowdown.

My forecasts last March are close to what the final demand numbers look likely to be for last year.

But 2023 is great deal harder to predict for everyone, hence my latest outlook for China’s PP demand (see the chart below), which includes the two extremes of our ICIS base case for 6% growth versus my worst-case downside of minus 5%.

“Citing high-frequency trackers, JP Morgan, according to a client note from its Asia team, said subway traffic has returned to about two-thirds of the normal average, with Beijing leading the recovery. Express package collection and delivery is back to about 90% of November’s peak levels and domestic air travel has bounced back to 70% of pre-pandemic levels,” wrote Barron’s, the financial news and analysis service, in an 11 January article.

If this level of recovery were to persist or even strengthen, the negative views I expressed in my 10 January post – when I looked at the prospects for China’s PE market – could be wrong.

In the post, I highlighted the risk that even if China gets well past peak infections and deaths by no later than Q2 2023, consumer spending may well remain muted because of:

- Increased rural economic inequality resulting from the pandemic (China was a very unequal country before 2020). This could limit the spending capabilities of less prosperous Chinese, which comprise some 1bn of the 1.4bn population. Migrant workers have lost income due to lockdowns. The lockdowns have also damaged the educational prospects of young urban residents.

- Youth unemployment is close to record levels. As of last August, one in five young people were said be out of work.

- Consumer spending by the around 400m residents who make up “rich China” may remain depressed relative to the 2009-2021 boom years, because of the implosion of the real-estate bubble. New home sales are projected by Citigroup to fall by a further 25% this year. ICIS polymer demand data show that the 2009-2021 surge in consumption was highly correlated to rapid growth in property lending. A return to the previous levels of credit availability for real estate seems impossible because of the extent of oversupply and bad debts.

The “trust” thing must be considered

We must not forget the impact of China’s rapidly ageing population, cumulatively a bigger challenge year by year.

“China is now set to “become old before it gets rich”. The number of those in its low-earning, low-spending perennials cohort [aged 55 plus] is set to jump by more than 50%, from 300m today to 475m by 2030. At the same time, its low fertility rate means the number of wealth creators [25-54] will fall by 100m,” said fellow ICIS blogger Paul Hodges.

Hear, hear.

How will China generate the welfare benefits it needs to pay for its rapidly ageing population now that the property bubble has imploded, given that the main source of local government financing has been land sales? This is just one of many challenges resulting from the greying of China’s population.

And what about the “trust” thing? We must address the sensitive subject of trust in the consistency of government policy direction because of the sudden reversal of zero-COVID policies. Uncertainty over whether there could be further sudden changes in policy direction may undermine both consumer spending and business investment.

“In some ways, Omicron is easier to predict than the Chinese government,” Jörg Wuttke, the president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, was quoted as saying in a 9 January Wall Street Journal article.

“We see that a more politicised environment makes figuring out what decision makers are about to do very difficult,” he added.

We must further consider the impact on the Chinese economy of persistently high overseas inflation, given that some 20% of China’s GDP is driven by exports.

But still, as the JP Morgan real-time economic data quoted earlier show, when a car goes from five miles an hour to, say, 30 miles an hour, that’s a 500% increase. Large parts of the economy were shut down during zero-COVID, so of course consumer spending will increase as sectors re-open.

The question is how much the metaphorical car will pick up speed relative to 2021 – the year before severe lockdowns and the end of the property bubble. On these terms, I maintain that there is a significant risk of a weaker recovery than is being priced in by stock-market investors.

As for global chemical and polymer markets, you should not need reminding that China is a huge, huge deal. Here is a reminder, anyway, using PP as an example.

Either a 79% global average PP operating rate in 2023 or just 76%

With China accounting for 40% of global PP demand in 2022, up from only 15% in 2000, we must consider very seriously the global impact of the earlier three scenarios for China’s PP demand in 2023.

Let’s start with the ICIS base case.

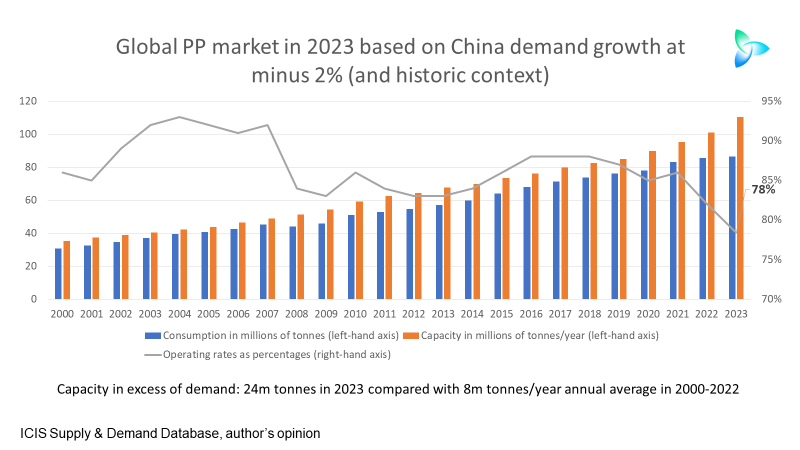

Even under the ICIS base-case China demand growth of 6%, we are forecasting a global operating rate of 79% this year and capacity greater than demand by 21m tonnes. This compares with an average annual global operating rate of 87% between 2000 and 2022. Annual average capacity surplus to demand was at 8m tonnes in 2000-2022.

A 2% decline in China growth would leave the market 2.8m tonnes smaller than our base case. This would in turn increase capacity surplus to demand – assuming, of course, that all the new plants come on-stream on schedule – to 24m tonnes. The global operating rate would slip to 78%.

The worst-case outcome, minus 5% growth, would leave demand 3.8m tonnes lower than our base and push surplus capacity to 25m tonnes. The global operating rate would slip to 76%.

Note that the two downside scenarios leave growth elsewhere in the world unchanged from the ICIS base case. This is unrealistic, I am afraid, given the importance of the Chinese economy to the rest of the world. Lower growth elsewhere would be inevitable.

Conclusion: Workshops and scenarios

As even our base case chart for PP shows (and it is a very similar story in PE), PP faces an historically difficult year, the worst since at least 2000.

This reflects the polycrisis we confront involving events in China, high levels of global inflation and the end of the benign geopolitical era that followed the collapse of the Berlin Wall. When you add growing sustainability pressures, the chemicals industry has probably never before faced such a difficult and uncertain operating environment.

So, what should you do? The answer is to get your teams together in “demand and supply” workshops to plan and constantly re-plan for 2023. And you must build deep and constantly revised scenarios for China and all the other markets.

As I’ve discussed before and as the chart below reminds us:

Making the right decisions week-by-week on sales targets for different countries and regions will make all the difference.

You can successfully take advantage of the mini troughs and dips on the left-hand side of the above V if you, say, accurately assess that the Turkey market will be stronger than the India market in March.

And this must be underpinned by constantly updated views on China.

For support in these workshops and scenario building, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.