By John Richardson

YOU MAY well have noticed that announcements of new cracker and derivatives projects continue at a fairly rapid pace despite today’s probably all-time-record levels of oversupply.

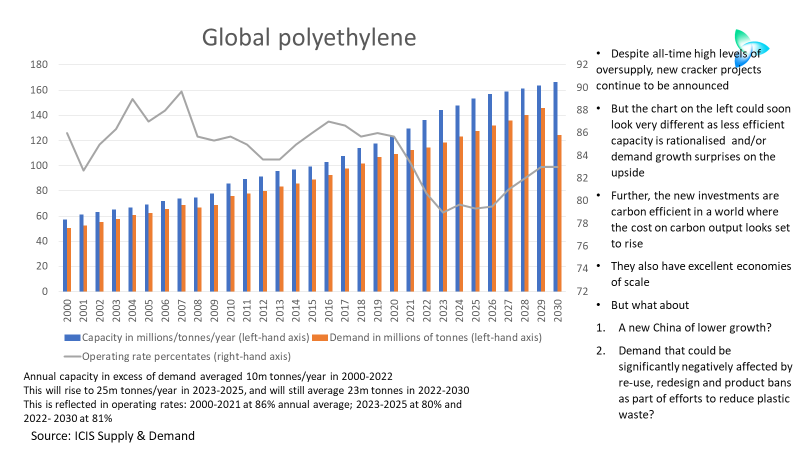

The chart below illustrates the extent of forecast total oversupply across the three grades of polyethylene (PE), using the ICIS Supply & Demand database base case assumptions. The pattern is similar in many other products.

The table below shows some of the cracker projects due on-stream over the next four years. A few of these projects have been announced since we entered what has been called a polycrisis (see definition below).

Saudi Aramco has big ambitions in crude-to-chemicals. The company sought to expand its “liquids to chemicals capacity to up to 4m barrels per day by 2030,” Saudi Aramco was quoted as saying in this 13 January ICIS news article on Aramco’s China plans.

“Aramco is working at tweaking the existing technologies and processes in an integrated refining complex to raise the chemical production level per barrel of oil from the regular 8-12 %, up to 50 %,” said ArabNews in this 25 November 2022 article, quoting from the company’s website.

“The term, [polycrisis], which was popularised last year by the economic historian and Davos attendee Adam Tooze, describes the simultaneous and overlapping crises facing the world today: a health crisis, a mounting climate crisis, a war in Europe, an inflation shock, democratic dysfunction and much more,” wrote Time in a 17 January article.

We must add the New China to this list. I was right. I predicted what would be happening in China today in 2021, and I have been warning this would eventually happen since 2014: A long-term moderation of demand growth as the country seeks new, more sustainable, growth. It needs a model that is sustainable in terms of both the economy and the environment.

Threats to China’s success in building this new model include its rapidly ageing population, growing geopolitical divisions with the US, a real estate-driven growth model that no longer works and severe economic inequality between rural and urban China.

We also need to consider the short and possibly even long-term impact on consumer spending and investment confidence of the sudden reversal of the zero-COVID policies.

Even the ICIS base case sees China’s synthetic resins growth moderating to around 2% over the next 20 years from the high single digits in 2000-2022.

But we need a nuanced and a constantly revised range of scenarios for China’s demand over the next two decades and more.

Could annual average growth be more than 2% for the resins or less? What would be the factors determining these two different outcomes?

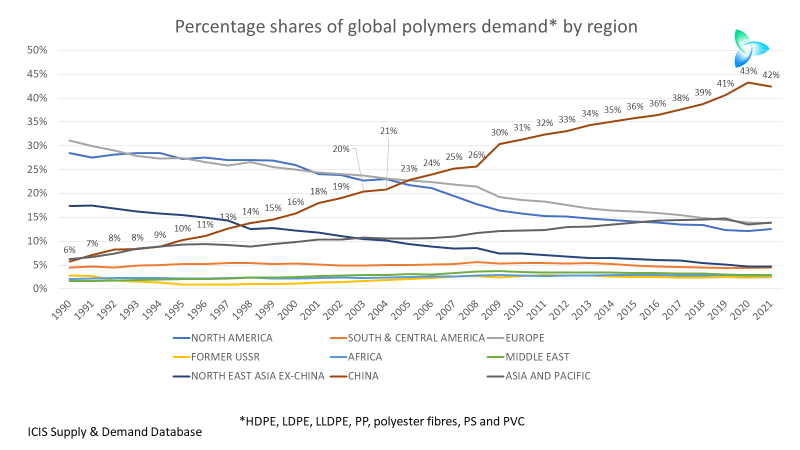

Just in case you’ve been living on Mars over the last 30 years and have as a result missed the importance of China to global demand, here is a reminder.

China accounted for just 6% of global demand for the seven big synthetic resins in 1990. This rose to 42% in 2021.

And, of course, China is by far the biggest importer of many of the major liquid petrochemicals and polymers. Even the ICIS base case sees China’s imports declining very sharply over the next 20 years as the country’s self-sufficiency increases.

Challenging the accepted wisdom of booming emerging markets demand

“Don’t worry,” I can you hear you saying, “even if Chinese growth slows down to around 2% per year, or even less, the developing world will pick up the slack. Just think of the prospects in Africa, Asia and Pacific and South and Central America as hundreds of millions more people rise out of poverty.”

As I’ve highlighted before, the potential demand growth in the developing world is huge.

This is because petrochemicals and polymers are intimately bound into the quality and quantity of life (ever-longer life expectancy) we take for granted in the rich world.

But I discussed in my 16 January LinkedIn post:

- Resealable packing and other efficiencies that reduce single-use virgin polymers consumption (re-use as well as redesign) could accelerate to the point where global demand declines.

- This could make nonsense of the conventional view that booming emerging market demand (people rising out of poverty) guarantees sunny uplands of demand for producers over the next 20-30 years. The “sunny uplands” view seems to be behind announcements of new projects over the last six months – along with the assumption that today’s record levels of oversupply will cause major rationalisation of less efficient capacity.

- Or I could be talking total and utter nonsense.

To find out who is right would require a very granular, bottom-up analysis of every end-use application for polymers, including, of course, into durable goods.

A call would have to made on each of the applications, on whether they could be banned and the extent to which they might be redesigned and re-used to cut back on virgin consumption.

And in parallel, of course, the re-use, redesign and ban solutions must tick the carbon box. Using complete lifecycle analysis, we must work out if each of the solutions is carbon positive or negative.

Further, we need to also evaluate the “societal good” resulting from plastics – for example, the importance of single-use plastics in medical supply chains and in reducing malnutrition through guaranteeing food arrives fresh where it’s needed.”

On granular bottom-up analysis, this is what my ICIS colleagues Kevin Swift, Nigel Davis and I plan to do with high-density PE (HDPE).

We will take the ICIS Supply & Demand Database’s estimate of HDPE demand by end-use application over the next 20 or so years and separate essential from non-essential uses, the latter involving assessments of demand that could be lost to product bans, re-use and redesign.

We will then compare the different demand outcomes with our base case and the impact on requirements for new capacities.

As plastics supply balloons, demand growth is increasingly challenged

See below a 13 January ICIS Insight from Nigel Davis that covers the same arguments, highlighting growing evidence of the toxicity of plastic waste and progress towards a global agreement on limiting plastic waste.

Print out, read and re-read, pin to your boardroom walls and use this article as the basis for scenario planning:

LONDON (ICIS)–Polyolefins supply is ballooning just as expectations of recession mount and longer-term prospects for demand growth look increasingly uncertain. Global operating rates are under intense pressure.

The modern world needs plastics, and producers are keen to supply what most see as a healthily growing market over time. Business strategies for the major producers, public and state-owned, are wedded to strong demand growth for these ubiquitous materials, driven particularly by demand from developing world economies.

Yet, nation states are becoming much more concerned about the plastics problem, not simply how plastics waste might be tackled but also how the use and thereby the production of non-essential plastics might be curbed.

Is the issue polarising then into one based on the essential nature of plastics in certain applications and non-essential use in others?

Industry’s argument that plastics are good and essential to a healthy modern lifestyle will be challenged on multiple levels in coming years as the downside of the plastics revolution is tackled more forcefully. Producers have a great deal to lose if a strategy miss-step takes them down a path along which there is little room to manoeuvre.

Real progress was made last year at the at the first UN Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-1) meeting on eliminating plastic waste in the environment. A foundation was laid for a global agreement not simply to end plastic waste but to address the full life cycle of plastics. The primary concerns are with protecting human health and the environment.

That plastics have become a health and environment issue shows how the pressure on continued capacity expansion and use of these materials is building and that the future demand growth expected currently might not be available to all.

As the concept of plastics use shifts from good to bad, what measures might be taken not simply to circularise sector markets but to curb plastics production and use?

Evidence on the harmful impact of plastics in the environment and when ingested is mounting.

The UK government recently highlighted new research showing that invasive species hitchhike on floating marine debris, mostly plastics, for example. It says that the UK continues to be a leading voice in tackling marine plastic pollution.

As a founding member of the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution the UK is calling for a target, under a proposed new legally binding international treaty, to “stop plastic from flowing into our lands and ocean by 2040”.

The HAC was formed late last year and is expected to underpin the UN INC-1 work. It now has 50 countries as members. The first of its three strategic goals, at the outset of plastic treaty negotiations, is to “restrain plastic consumption and production to sustainable levels”, it says.

At the same time plastics users are being targeted. A lawsuit brought in France against Danone this week, for example, targets an absolute reduction in plastics use by the food company. Recycling is seen as inadequate.

The lawsuit is brought under the French Duty of Corporate Vigilance Law, which puts the onus on companies to adequately identify the risks to human rights and the environment of their activities.

While the industry pins its future very much on recycling and carbon footprint reduction, it still believes in strong underlying demand growth for plastics of all sorts. However, that position is increasingly challenged.

Some 50 nations are now members of the HAC. The international, legally binding treaty they are pursuing looks to bans and restrictions on problematic plastics, global sustainability standards and “mechanisms for strengthening commitments, targets and controls over time”.

The low-carbon polymers and market share arguments

But companies behind the crackers due on-stream over the next four years emphasise the low-carbon output of what’s being planned, whether this is through carbon capture, electric furnaces, long-term plans for green hydrogen or other technologies.

Some of the low-carbon technologies will hinge on the availability of abundant and therefore very cheap renewable energy in regions such as the Middle East.

Cheap energy supply could combine with very good economies of scale to give the new cracker announcements a competitive edge. This may force the closure of less efficient plants.

And, anyway, the shocking PE chart that I showed earlier isn’t likely to be the reality by the time the new projects start-up. A lot of capacity will likely have to be shut down before the projects come on-stream, given the extent of today’s oversupply.

Demand growth may also pick up. China’s polymers demand may, as I said earlier, grow by more than 2% per annum over the next 20 years that we expect in our base case. Global inflation could have also peaked.

We may also be heading towards a world where low-carbon petrochemicals and polymers are the only market, whatever is the remaining demand as re-use and re-cycling accelerate

Europe is the world’s second-biggest PE and polypropylene (PP) import market. This 17 January ICIS Think Tank podcast discusses the path towards the potential inclusion of petrochemicals in the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

EU imports of certain goods and selected precursors whose production is carbon intensive will be subject to an additional “fair price” on the carbon emitted under the CBAM. The CBAM will begin on 1 October 2023.

As evidence of climate change grows, we could see more and more legislation elsewhere that penalises higher-carbon polymer production.

I have been pondering whether low-carbon petrochemicals and polymers might carry “green premiums” – higher prices per tonne, as they would help meet brand-owner carbon pledges.

“But when leaded gasoline was being phased out [from the 1970s until its complete disappearance in 1996], it wasn’t the case that unleaded gasoline carried a premium. It was instead rather that you increasingly could not sell leaded gasoline, so you had to make unleaded gasoline at no extra margin,” said one of my contacts.

This seems to make more sense. Moving to low-carbon petrochemicals production may be a question of survival and market share rather than higher pricing, supporting the logic of many of the new cracker announcements.

Conclusion: Talking to the C-suites

All the above complexities will reshape our industry over the next few years. So will the possibly that global GDP growth will decline or even reverses as the economic, social and political damage from climate change accelerates.

It would thus be fascinating to sit down with the C-suite executives of the companies behind the wave of new cracker announcements.

Luckily, this what ICIS news, and our magazine ICIS Chemical Business, does. Watch out for our C-suite interviews in 2023.