By John Richardson

AGAIN, DON’T SAY I DIDN’T WARN YOU. The return of container freight rates to their pre-pandemic levels has led to a re-globalisation of the global polyethylene (PE) business with potentially major negative implications for the markets outside China.

As I first warned would eventually happen (see this April 2021 post), oversupply trapped in China by expensive container freight and a lack of availability of container space can now more easily move around the world.

What could, of course, limit the negative impact on the markets outside China is the famous old “producer discipline”.

A case in point is the higher number of cracker-to-PE turnarounds taking place in Q1 this year, which is I again said would be the case last November. Liquids crackers in northeast and southeast Asia have also cut their operating rates in response to the worst market conditions we have probably ever seen.

But the new capacity that has already been built has to come onstream. Steel in the ground means that it must run at some point, and the salient facts remain:

- Global capacity exceeding demand is forecast by ICIS to average 24m tonnes in 2023-2025 and to reach 25m tonnes this year

- This would compare with 10m tonnes annual average capacity more than demand in 2000-2022

A substantial lump of this new capacity is also ethane-based and so has excellent economics. Another large chunk of the projects is in China. While the Chinese complexes are liquids based, the costs and risks of capital are said to be low, thanks to support from local and central governments.

Here is the other thing as well: Why delay your start-up because market conditions are weak, when your debt repayments are due to kick in on a specified date? Some return on investment is better than no return at all.

Southeast Asia: A case study in risk

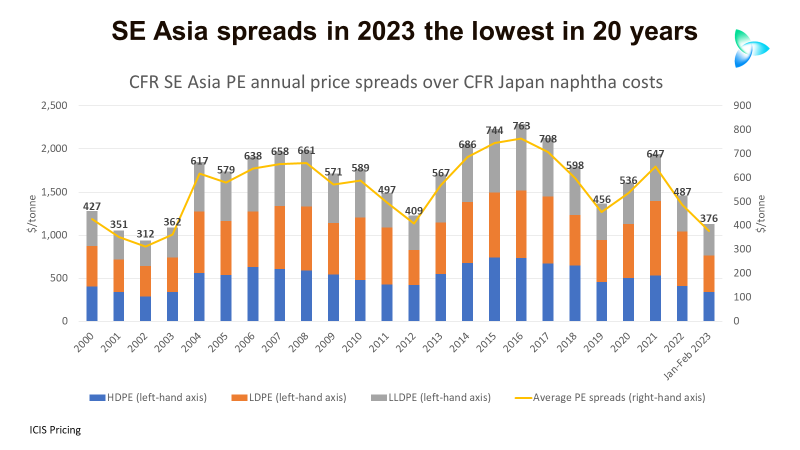

The chart below shows SE (southeast) Asia CFR (cost & freight) PE price spreads between CFR Japan (the benchmark for the whole of Asia) naphtha costs. Spreads remain the single best tool for assessing supply and demand balances in any country or region.

In 2022 relative to what happened in China (see the next slide), southeast Asia spreads held up very well. Last year’s annual average spread for three of the major grades was $487/tonne, which compares reasonably favourably with the $563/tonne 2000-2021 annual average.

As was the case with the other regions and as described above, high container costs and the lack of container space limited the ability of the big exporters to shift oversupply in China to southeast Asia.

But now that container rates are back to where they were before the pandemic, this year’s southeast Asia average PE spread at $376/tonne is the lowest since 2003. This, to me, is a clear sign of the knock-on effects of the very weak China market and record levels of global below.

Now let us look what’s happened with China spreads.

The China average PE spread so far in 2023 is just $285/tonne, the lowest since our price assessments began in 1993. Note that the China assessments started seven years before the southeast Asia assessments.

This year’s record-low China spread undermines all the talk about a big China recovery following the end of the zero-COVID restrictions. Regular readers of the blog would not be surprised that the recovery has yet to materialise.

Prices will go up and they will go down week by week in China, creating waves of confidence and pessimism. But these price movements don’t tell the real story, whereas spreads do.

What we know from the history of the PE industry is that weak spreads translate to poor market conditions. So, filter out all the noise and concentrate on this: Until China’s spreads are much closer to their 2000-2021 annual average of $532/tonne, there will have been no full recovery. And right now, with spreads this year at just $285/tonne, we are long way from any kind of recovery.

The next chart compares the premiums and discounts for annual average southeast Asia PE spreads over those in China between 2000 and 2023.

We can again see the protection afforded the southeast Asia market in 2022 from China oversupply by high container freight costs and container shortages.

In 2021, as freight rates rose, the southeast Asia premium climbed to $111/tonne from just $37/tonne the previous year. Then in 2022, the premium reached a record high of $165/tonne, although during the second half of 2022 monthly premiums fell in line with falling freight rates.

So far in 2023, the premium is $91/tonne, still higher than the longer-term trend. Sadly, however, I believe it has further to fall as the weak China market drags southeast Asia further down.

Now let us look at the actual average PE price differentials between southeast Asia and China, again from January 2000 when our southeast Asia assessments began. This is from the angle of SEA price premiums, and very occasionally discounts, over China PE prices.

The southeast Asia price premium over China reached an all-time high of $282/tonne in April 2022. This was once again because of the freight issue.

The price premium had fallen to $53/tonne in December, but by February this year had recovered to $99/tonne.

Southeast Asian producers, though, should be careful what they wish for. A combination of lower freight rates and the weak China market is said to have led to substantial re-exports of PE to southeast Asia from China.

PE had perhaps been exported to China because producers and traders had been persuaded by all the talk of the big post-zero COVID recovery. Instead, though, the resins sat unsold in bonded warehouses before being re-exported.

Just to complete the picture, and for your reference, see below the actual average monthly southeast Asia PE prices compared with those in China from January 2000 until February 2023.

Conclusion: These are incredibly difficult times

The only way that PE producers can prosper, or at least minimise their losses, during this downturn is to realise that we are going through incredibly difficult times.

If they are instead misled by the talk of a very big China recovery in 2023, they could make very costly mistakes on production and sales targets.

What’s required, as I have been emphasising since January, is for producers to focus on every market globally. Deeper analysis of supply, demand and pricing trends in each of the global markets is essential.

As with every previous downturn I have seen, this type of analysis can enable the producers to successfully ride the mini troughs and peaks represented by the left-hand side of V below – the downturn.

When will the market reach the bottom of the V and then see the upturn on the right-hand side? In my view, in H2 2024 at the very earliest.